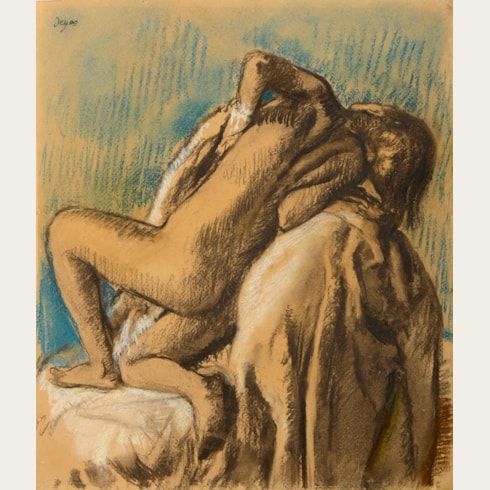

Edgar DEGAS

(Paris 1834 - Paris 1917)

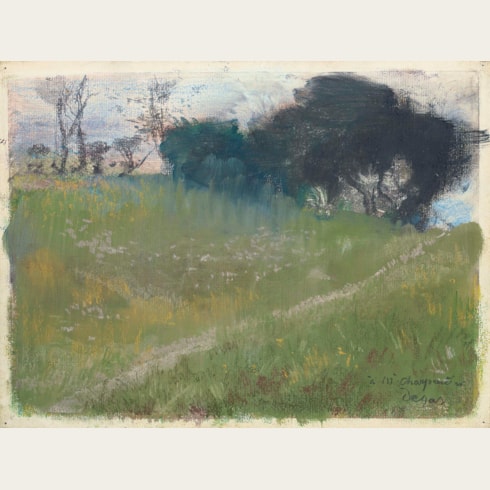

Volcano (Le Vésuve: Souvenir de Naples)

Stamped Degas in red ink at the lower left.

247 x 296 mm. (9 3/4 x 11 5/8 in.) [platemark]

269 x 319 mm. (10 5/8 x 12 1/2 in.) [sheet]

Many of Degas’s pastel drawings were made over a monotype base, a practice he seems to have begun around 1876 or 1877. A monotype is made by applying either black ink, oil paint, or oil diluted with turpentine to a non-absorbent surface such as copper or glass. The image is transferred onto a sheet of paper by laying it onto the plate and applying pressure, either by rubbing or by passing through a press. While usually only one impression of each print could be made (hence the term ‘monotype’), occasionally a second, fainter impression could be pulled before the ink was used up. It would be this second pull that would be extensively reworked in pastel by Degas, although he would occasionally retouch the first pull as well. As one recent scholar has noted, ‘He began to use pastel, gouache and distemper to colour the faint second impressions of monotypes...these opaque media, of optimum covering power, allowed him sometimes to build the prints into more elaborate compositions, often effectively masking the presence of the monotype base.’ The artist himself seems to have avoided the term ‘monotype’, preferring instead to define these works as ‘dessins fait à l’encre grasse et imprimé’ (‘drawings made with greasy ink and put through a press’), which is how they were described when a group of them. depicting café and theatre scenes, were exhibited at the third Impressionist exhibition of 1877.

Volcano (Le Vésuve: Souvenir de Naples) is one of a group of around three dozen pastel-worked monotype landscapes executed by Degas between 1890 and 1892. It was in October 1890, while staying at the home of the painter and printmaker Georges Jeanniot in the village of Diénay, near Dijon in Burgundy, that Degas began to produce a new series of colour monotype landscapes, many enriched with pastel. Although he had first made pastellized monotypes a decade or so earlier, the ones produced at Diénay, and in the months following, were in a larger format, and were more technically audacious. Degas worked on the plates using diluted oil paint, creating effects by rubbing the medium with cloths or brushes, sometimes using the end of a brush handle or his finger to create lines or other forms.

Georges Jeanniot has left a fascinating account of Degas at work on the first of these monotypes in his studio in Diénay: ‘And now, take me to your studio’, Degas said to me as we were leaving the table…‘I have been wanting for so long to make a series of monotypes!’…Once supplied with everything he needed, without waiting, without allowing himself to be distracted from his idea, he started. With his strong but beautifully-shaped fingers, his hands grasped the objects, the tools of his genius, handling them with a strange skill and little by little one could see emerging on the surface a small valley, a sky, white houses, fruit trees with black branches, birches and oaks, ruts full of water after the recent downpour, orangey clouds dispersing in an animated sky, above the red and green earth. All this fell into place, coming together, the tones setting each other off and the handle of the brush traced clear shapes into the fresh colour. These lovely things seemed to be created without the slightest effort, as if the model was in front of him…Once the proof was obtained, it was hung on lines to dry. We would do three or four a morning. Then, he would ask for some pastels to finish off the prints and it is here, even more than in the making of the proof, that I would admire his taste, his imagination and the freshness of his memories. He would remember the variety of shapes, the construction of the landscape, the unexpected oppositions and contrasts; it was delightful!’

Unlike his earlier monotypes, which were made using black printer’s ink, in the monotype landscapes of the early 1890s Degas used coloured pigments, in the form of oil paint, adding a second layer of colour with the subsequent application of pastel. As Eugenia Parry Janis has noted of these landscapes, ‘the most dramatic spatial effect is not in the view represented but rather in the optical vibration set up between the two layers of color. These layers consist of two entirely different physical substances, necessarily handled by the artist in different ways. The matte striated monotype color always sits behind the crumbly light-catching, usually brighter taches of pastel, spaced with plenty of room allowed for the base to show through.’ At other times, however, Degas chose to completely cover the monotype base with his reworkings in pastel. As Richard Kendall observes, ‘The relationship between this pastel restatement and the original printed image varies a great deal, from landscape to landscape…Degas allowed pastel to transform his first conception in certain prints, challenging outlines and swamping earlier forms, and even obliterating the monotype completely.’ Degas is said to have referred to these pastellized monotypes as ‘imaginary landscapes’.

The present sheet has long been regarded as inspired by the artist’s memories of Vesuvius. Degas first visited Naples, where his grandfather René-Hilaire De Gas had settled and established a successful career as a banker, in July 1856. The artist stayed with his Neapolitan relatives at the family home in the Palazzo Pignatelli di Monte e Leone at 53 Calata Trinità Maggiore in Naples. (He also visited Rome and Florence, and was to spend almost three years in Italy during this first trip to Italy.) He returned again to Naples in 1886 and 1906 and, as Jane Munro has noted, ‘Although his visits were infrequent in later life, Degas remained very attached to the city most closely associated with his Italian roots, and as he aged was said to increasingly assume the bearing of a distinguished Neapolitan.’ As Munro further notes of the present sheet in particular, ‘in 1892 Degas produced from memory a monotype of the city’s most distinctive landmark, Mount Vesuvius, a topographical feature that had been a magnet for European landscape painters since at least the seventeenth century…Distilled from a decades-old visual memory, Degas’s monotype of Vesuvius is predominantly rendered in warm tones of olive green and rust-orange pastel, which create a credible colouristic equivalent to the molten mountain as it spews forth burning lava and belches black smoke and ash from its cone. That Vesuvius occupied a special place in Degas’s affection is suggested by his acquisition in the 1890s of a group of works depicting the volcano by friends and fellow artists, including Giuseppe de Nittis and Ludovic Lepic…Visual stimuli apart, Degas’s thoughts might have turned to Naples in 1892 for more prosaic reasons, as he read reports in Parisian newspapers of the eruptions of both Vesuvius and Mount Etna that occurred that summer. Clearly his rough-hewn monotype is in no sense an ‘illustration’ of the volcanic event, but instead has elements in common with the barren, inhospitable terrain that contemporaries discerned in Degas’s other monotypes of this date: ‘landscapes’ that for one commentator evoked the ‘strangest, wildest country…mountainous land of volcanic formation. Strange, fantastic-shaped peaks show sharply against the sky’.’

Some twenty-five of Degas’s landscapes executed in pastel over monotype, including the present sheet, were exhibited at the Paris gallery of his dealer Paul Durand-Ruel in November 1892. This was to be, in fact, the only true one-man exhibition held in Paris in Degas’ lifetime. Although the show was not a commercial success, with Durand-Ruel buying almost the entire show for stock, the works themselves were greatly admired, in particular for the range of brilliant colours seen in many of them. One critic described the exhibition as ‘the most extraordinary event of the season’, while Camille Pissarro wrote to his son Lucien that ‘Degas is having an exhibition of landscapes; rough sketches in pastel that are like impressions in colors, they are very interesting, a little ungainly, though wonderfully delicate in tone...these notes so harmoniously related, aren’t they what we are seeking?...Let me add that the landscapes are very fine.’ As a modern scholar has noted of the pastel monotype drawings shown in the Durand-Ruel exhibition, ‘These landscapes are far from literal, the configurations of the terrain often fantastic, with monotype in color providing a mysterious background against which the pastels seem to glow. The romanticism of these works suggests more of an affinity with the works of Turner than any other artist.’

Writing of the monotype landscapes by Degas of the early 1890s, Jean Sutherland Boggs noted that ‘they were not a countryman’s view of nature. Essentially they were visionary, romantic, often arrived at by accidents that took place in wiping, scraping, and printing the monotypes. They could be heightened or even covered by the highly controlled application of pastel, but this was done freely, emotively, and often theatrically. Even when Degas took two impressions of the same print and used different colors of pastel so that one would suggest autumn and one spring, those colors still seem more romantic than natural. But they are wonderfully evocative landscapes, nevertheless.’

The scholar Ann Dumas has noted the possible influence of Degas’s friend, the Italian artist Giuseppe de Nittis, on his pastel landscapes in general, and on the present sheet in particular: ‘One of the most fascinating connections between Degas and De Nittis is to be found, surprisingly, not in the urban world at all, but in landscapes. De Nittis’s landscapes are a somewhat neglected aspect of his work that reveals a visual power quite different from his more familiar views of fashionable Paris. Similarly, Degas’s landscapes are a sporadic and a less familiar dimension of his work. In his remarkable series of monotype and pastel landscapes of 1890, the mysterious textures and veils of colour, in which topography blends with landscapes of the mind, suggests comparisons with De Nittis’s misty, mountain views. Degas had responded to the Neapolitan scenery in his youth, a fact that perhaps made him receptive to his friend’s Italian landscapes. He surely had De Nittis’s views of Vesuvius in mind when, in the 1890s, he produced his own monotype and pastel image of the volcano.’

The particular influence of Japanese prints, which Degas is known to have collected, on works such as the present sheet may also be noted. As Kendall has pointed out, ‘The extreme formal simplicity of Degas’ landscapes and their unorthodox, even exotic, colour had other resonances for his first audience…Though variously worked in pastel, Degas’ pictures conformed to the modest dimensions of framed prints and were generally, if erratically, identified with them. For many visitors at this period, such a display would have been accompanied by another, even more specific, association, and one that several of Degas’ contemporaries were at pains to point out. This was with the Japanese wood-block print, one of the most widely collected and influential art forms of the late nineteenth century.’ As the same scholar further noted, with particular reference to the present sheet, ‘Degas’ landscapes were seen by his contemporaries in the context of Japanese art…The japonisme of Degas’ monotypes, which was so apparent to [contemporary writers such as] Philip Hale and Daniel Halévy, needs some elucidation today. At its most brazen, it provided the motif for Vesuvius, with its unmistakable echoes of Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji and of Mount Fuji in Clear Weather…in particular. Though slightly less wide than the Hokusai, Degas’ image is almost exactly the same height, and its similar purple-blue foreground and roseate volcano seem to offer a Europeanised version of this most celebrated of oriental icons.’

As Kendall and Jill DeVonyar note elsewhere, ‘[Degas’] picture of a volcano, posthumously entitled Vesuvius, has a simplicity of color and structure, and a dominant conical form at its center that are irresistibly reminiscent of Hokusai’s iconic print of Mount Fuji, another recently active volcano. Like the Hokusai, Degas’ landscape resonates with a surprising warmth from the liberal use of reddish brown against its cooler tones, creating a depth and complexity within an otherwise stark design. A broad horizontal band at the lower edge of both works increases this resemblance, which is further strengthened by their similarity in scale…The Fuji-Vesuvius conjunction was surely a contrived and knowing gesture by the artist, inviting comment from his erudite friends and wittily testing the equivalence between some of his own conceptions and their Japanese beginnings.’

The first owner of this pastel monotype was Gustave Pellet (1859-1919), a publisher of prints and art books, who acquired the work at the second Vente Degas in December 1918. Soon afterwards, Volcano (Le Vésuve: Souvenir de Naples) entered the collection of the noted Parisian amateur Marcel Louis Guérin (1873-1948), who assembled a superb group of 19th century prints - with an emphasis on the graphic work of Degas, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Jean-Louis Forain - in the first two decades of the 20th century. (He also published important catalogues and articles on the prints of these artists, as well as Paul Gauguin and Edouard Manet.) Following the dispersal of his collection of prints at auction in 1921 and 1922, Guérin built a second collection devoted to 19th and early 20th century drawings, including works by Degas, Delacroix, Forain, Manet, Renoir, Rodin and Toulouse-Lautrec, part of which was sold at auction in Paris in 1932.

Provenance

Gustave Pellet, Paris

Marcel Guérin, Paris

Private collection, Paris, in 1973

Eberhard Kornfeld, Bern (Lugt 913b), with his mark on the backing board

Thence by descent.

Literature

Exhibition