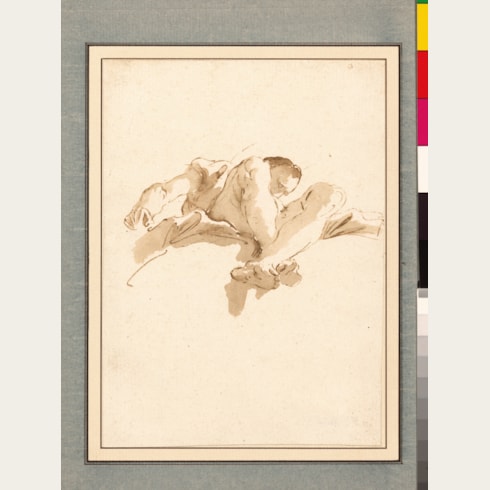

Giovanni Battista TIEPOLO

(Venice 1696 - Madrid 1770)

A Caricature of a Standing Man, Seen from Behind

Numbered 40 at the upper left, and 14 on the verso.

Inscribed [o]riginali del suo tempo farli in caricatura / Servirono di tipi à suoi quadri di maschere e cort[i?] / [d]isegno originale di on the reverse of the old mount.

164 x 82 mm. (6 1/2 x 3 1/4 in.)

Assuming that there was a Tomo primo and a Tomo secondo (quite possibly the two albums recorded in the Algarotti-Corniani collection in 1854), and a roughly equal number of drawings in all three albums, it may be determined that there must have been at least three hundred of these caricatures, and perhaps even as many as between four and six hundred in total. Around two hundred examples survive today, most of which are by Giambattista Tiepolo. They must have remained in the family studio after the elder Tiepolo’s death, since several were adapted by Domenico Tiepolo for figures in his late series drawings of the 1790s, notably the so-called ‘Scenes from Contemporary Life’ and the Punchinello series. Apart from the drawings known to have come from the Tomo terzo di caricature album and a group of some twenty caricatures in the Museo Civico Sartorio in Trieste, almost every other known Tiepolo caricature drawing has cut corners, which again suggests that they were once pasted into albums.

Giambattista Tiepolo’s caricatures seem to have been done for his own amusement, and also – albeit perhaps incidentally - as a source of figural types for his sons. These delightful drawings, in the words of one author, ‘call for no elaborate explanations – they are so simple and direct they speak for themselves. I do not fancy that they served any directly useful purpose or that they were ever intended as notes or sketches for larger or more important undertakings...They are the fruit of the artist’s leisure hours, the work of a man for whom the act of drawing was always the source of the keenest of pleasures...they are the work of a man who was the most gifted artist of his generation and are the outcome of that same calligraphic skill and acute observation that contributed so largely to the success of his major achievements.’

In these charming works, Tiepolo may have been inspired by the caricature pen drawings of 17th century artists such as Annibale Carracci, Pier Francesco Mola and Guercino, while older contemporaries such as Pier Leone Ghezzi in Rome and Marco Ricci and Anton Maria Zanetti in Venice also produced caricature drawings. However, Tiepolo tended not to introduce into his drawings the unsympathetic and often malicious inferences typical of the caricatures of these earlier artists. As one scholar has noted, ‘Often a Tiepolo caricature will evoke a kindly smile; at other times, compassion or curiosity. Whatever the response, however, the artist’s most poignant images are to be found among his caricatures. The compromise between style, license, and observation which they represent opened caricature fleetingly to a new expressiveness, a glimpse of a loftier mode of feeling.’

Giambattista Tiepolo’s caricature drawings have generally been dated to his last Venetian period, between his return from Germany in 1753 and his departure for Spain in 1762. As has been noted by one recent scholar, ‘By the time Giambattista turned to caricature, he was in his fifties and well established, with two grown sons following in his creative footsteps...These drawings expressed his lighter side, describing, in an economical yet convincing manner, the quirkier and funnier aspects of the men who crossed his path day by day. Over time, Giambattista produced a fascinating sampling of society, from noblemen, priests, and senators, to merchants, dockworkers, cooks, and artisans...Caught unawares, these men were reduced to their essentials, summarized most effectively through swift and insightful strokes of the pen...[They are] a brilliant blend of observation, memory, and distillation.’

In many of these caricatures the subject is seen from behind; indeed, this is a particular characteristic of caricature drawings by both Giambattista and Domenico Tiepolo. As another scholar has recently written of this type of lively caricature, ‘Tiepolo did not represent specific people but rendered generalized types that must have been immediately recognizable to contemporaries. Their gestures are minimal, the details of their clothes are understated, and indications of setting are scant. Here, even their faces are not shown, yet enough is communicated by their physiques, shoulders, stances, and costumes to distinguish types.’

This drawing may be presumed to have originated in the collection of the Conti Valmarana of Vicenza, which seems to have included a large number of Tiepolo caricatures. (It should be noted that both Giambattista and Domenico Tiepolo worked at the Valmarana family villa in Vicenza in 1757.) The caricature drawings associated with the Valmarana collection are, for the most part, depictions of single figures, with most seen from behind, and all have cut corners. Thirty-two of the caricatures from the Valmarana collection were acquired at an unknown date before 1959 by the German-born dealer and collector Paul Wallraf (1897-1981), and of these, fifteen examples are today in the Robert Lehman Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The leading painter in Venice for much of his career, Giambattista Tiepolo was also undoubtedly one of the finest Italian draughtsmen of the 18th century. That his drawings were greatly admired in his lifetime is confirmed by contemporary accounts; indeed, as early as 1732 the writer Vincenzo da Canal remarked that ‘engravers and copyists are eager to copy his works, to glean his inventions and extraordinary ideas; his drawings are already so highly esteemed that books of them are sent to the most distant countries’. From the late 1730’s until his departure for Spain in 1762, Tiepolo enjoyed his most productive period as a draughtsman, creating a large number of vibrant pen and wash studies that are among the archetypal drawings of the Venetian Settecento. As one recent scholar has commented, ‘From the start of his career [Tiepolo] had enjoyed drawing as an additional means of expression, with equally original results. He did not draw simply to make an immediate note of his ideas, nor to make an initial sketch for a painting or to study details; he drew to give the freest, most complete expression to his genius. His drawings can be considered as an autonomous artistic genre; they constitute an enormous part of his work, giving expression to a quite extraordinary excursion of the imagination; in this respect, Tiepolo’s graphic work can be compared only with that of Rembrandt.’

Tiepolo’s drawings include compositional studies for paintings and prints, drawings of heads, figure studies for large-scale decorations, landscapes and caricatures, as well as several series of drawings on such themes as the Holy Family. Many of these drawings were bound into albums by theme or subject, and retained by the artist in his studio as a stock of motifs and ideas for use in his own work, or that of his sons and assistants.

Provenance

Possibly the Conti Sacchetto, Padua

Possibly Paul Wallraf, Paris and London

Private collection.