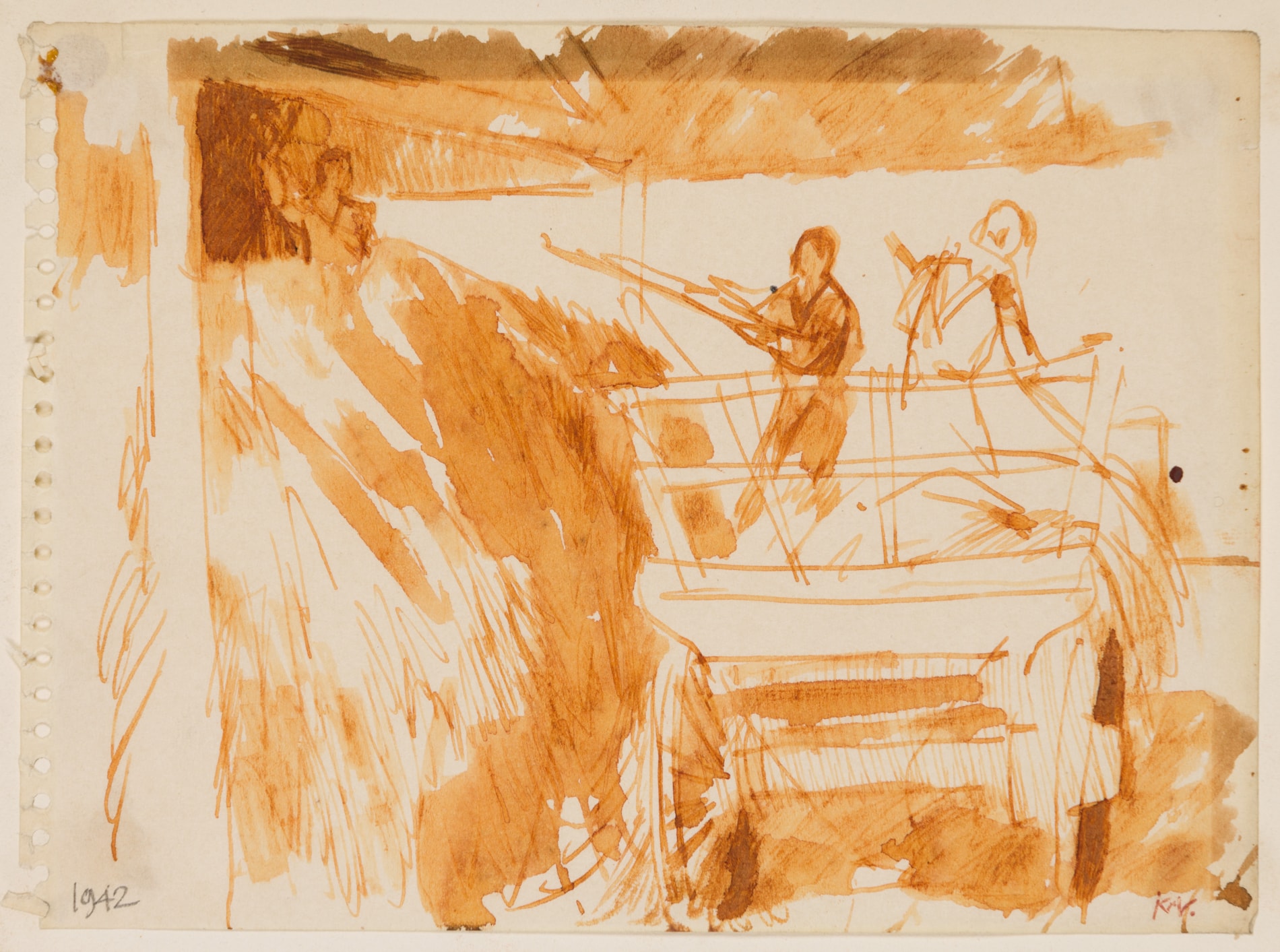

Keith VAUGHAN

(Selsey 1912 - London 1977)

Stacking Hay

Pale brown ink and brown wash, on a page from a sketchbook.

Signed with the artist’s initials KV. at the lower right.

Dated 1942 at the lower left.

126 x 173 mm. (5 x 6 3/4 in.) [sheet]

Signed with the artist’s initials KV. at the lower right.

Dated 1942 at the lower left.

126 x 173 mm. (5 x 6 3/4 in.) [sheet]

While serving in the NCC during the Second World War, since there was a limited range of media that could be carried in a regulation army knapsack, Keith Vaughan became adept at expressing himself through the graphic mediums of ink, crayon and gouache. Dated 1942, the present sheet is a page from one of the many small sketchbooks that Vaughan filled with figure, landscape and compositional studies in pen and ink during this period. In the summer of that year the artist was stationed at a barracks in Codford in Wiltshire, near Ashton Gifford House, where he and his fellow soldiers were tasked with clearing the overgrown grounds. The early 1940s found Vaughan executing numerous drawings of his surroundings, the barracks and fellow soldiers and labourers, some in sketchbooks and some – known as the ‘Army Drawings’ - on much larger paper and typically filled out with gouache. Among his finished works of this period is a watercolour of The Wall at Ashton Gifford, today in the collection of the Manchester Art Gallery.

A stylistically comparable drawing of soldiers raising a tent, of the same date and probably from the same small sketchbook, was formerly in the Tim Ellis collection and was sold at auction in London in 2014. What may be the sketchbook itself, or a similar one, used at Codford in the summer of 1942 and containing fourteen leaves, was acquired from the artist by his friend Klaus Peter Adam and recently appeared at auction.

A stylistically comparable drawing of soldiers raising a tent, of the same date and probably from the same small sketchbook, was formerly in the Tim Ellis collection and was sold at auction in London in 2014. What may be the sketchbook itself, or a similar one, used at Codford in the summer of 1942 and containing fourteen leaves, was acquired from the artist by his friend Klaus Peter Adam and recently appeared at auction.

Born in Sussex, Keith Vaughan moved with his family to North London around the start of the First World War. He showed a gift for the arts from a very young age, earning a Royal Drawing Society certificate at the age of seven, but received almost no formal artistic education and was mostly self-taught. While at boarding school, Vaughan was given special entitlements to study art, since he was the first student to specialize in it, and it was at the Christ’s Hospital school that he mounted his first exhibition of landscapes. At the age of nineteen, Vaughan began work as a trainee in the art department of an advertising firm, where he remained until just before the start of the Second World War. In 1939 he left the firm and moved to the country, intending to paint for a year; this would be the first consistent time Vaughan would spend as a fine artist since his school days. It was also at around this time that he began keeping a written journal, a practice he maintained until his death, and which eventually amounted to some 750,000 words contained in sixty-one volumes.

During the Second World War, Vaughan declared himself a conscientious objector, and was conscripted into the Non-Combatant Corps (NCC), working as a labourer in Wiltshire and Derbyshire. It was during the war that, through the collector Peter Watson, Vaughan came into contact with such contemporaries such as Graham Sutherland and John Minton, both of whom were to be highly influential on the artist’s developing career, as well as John Craxton. It was also during this time that Vaughan began exhibiting his work, first in a group exhibition of War Artists organized by Kenneth Clark at the National Gallery in London in 1943, followed by a small show of drawings – of army subjects, landscapes and figures – at the Alex Reid & Lefevre Gallery in London at the end of the following year.

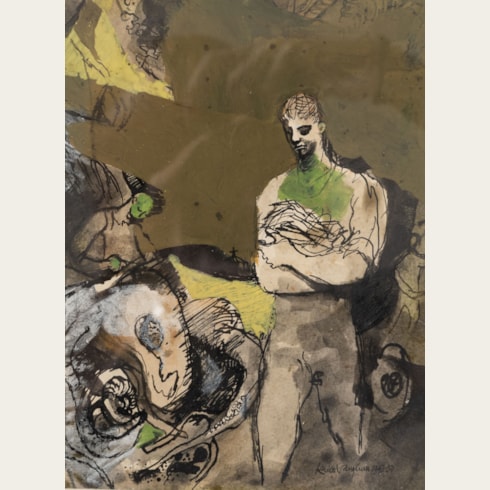

After the war Vaughan began to work consistently in oil paint. Leaving the army in 1946, he taught part-time at the Camberwell School of Art and held the first exhibition of his paintings and gouaches at the Lefevre Gallery. The same year he moved into a house and studio in Maida Vale that he shared with Minton, working alongside him for the next six years. Vaughan’s postwar style was very different from that of the 1930s, with the artist focussing on oil painting and more fully finished compositions and turning away from the English Neo-Romanticism of his earlier work. He also produced designs for book jackets, magazine illustrations and advertisements, and received an important commission for a fifty-foot-long mural for the Dome of Discovery, a temporary building erected on the South Bank for the 1951 Festival of Britain, which is now lost. Focussing on the nude male form, Vaughan’s work also became more abstract; in 1952 he saw an exhibition of the work of Nicolas De Staël and came away impressed with the French artist’s abstractions. Although today regarded as perhaps the pre-eminent painter of the male nude of the postwar period, Vaughan’s concurrent interest in landscape painting, inspired by his travels around Britain, Ireland, France, Italy, Greece, Spain and Morocco, is such that almost half of his extant paintings are landscapes.

By the first half of the 1950s Vaughan was exhibiting regularly at the Lefevre, Redfern and Leicester Galleries in London, and also at Durlacher gallery in New York. In his later years he taught at the Central School of Art and the Slade School of Art, as well as at Iowa State University in America. The peak of Vaughan’s success came in the 1950s and early 1960s, culminating in a major retrospective exhibition of his work, numbering over three hundred paintings, gouaches and drawings, at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London in 1962. The exhibition was a critical success, one reviewer commenting that ‘One remains in no doubt, within five minutes of entering the retrospective exhibition of paintings and drawings by Keith Vaughan, that one is in the presence of a very considerable artist and a very consistent one.’ Not long after this, however, the artist began to fear that his works were being overshadowed by newer movements in art, notably British Pop Art and Abstract Expressionism, though he continued to have regular exhibitions in galleries in Britain and America, notably at the Waddington Galleries in London. His health began to worsen and he underwent a series of major operations that sapped him of his energy and exacerbated a tendency to depression. On the morning of 4 November 1977, suffering from terminal cancer, Vaughan committed suicide with a fatal overdose of pills, writing in his journal to the very end.

During the Second World War, Vaughan declared himself a conscientious objector, and was conscripted into the Non-Combatant Corps (NCC), working as a labourer in Wiltshire and Derbyshire. It was during the war that, through the collector Peter Watson, Vaughan came into contact with such contemporaries such as Graham Sutherland and John Minton, both of whom were to be highly influential on the artist’s developing career, as well as John Craxton. It was also during this time that Vaughan began exhibiting his work, first in a group exhibition of War Artists organized by Kenneth Clark at the National Gallery in London in 1943, followed by a small show of drawings – of army subjects, landscapes and figures – at the Alex Reid & Lefevre Gallery in London at the end of the following year.

After the war Vaughan began to work consistently in oil paint. Leaving the army in 1946, he taught part-time at the Camberwell School of Art and held the first exhibition of his paintings and gouaches at the Lefevre Gallery. The same year he moved into a house and studio in Maida Vale that he shared with Minton, working alongside him for the next six years. Vaughan’s postwar style was very different from that of the 1930s, with the artist focussing on oil painting and more fully finished compositions and turning away from the English Neo-Romanticism of his earlier work. He also produced designs for book jackets, magazine illustrations and advertisements, and received an important commission for a fifty-foot-long mural for the Dome of Discovery, a temporary building erected on the South Bank for the 1951 Festival of Britain, which is now lost. Focussing on the nude male form, Vaughan’s work also became more abstract; in 1952 he saw an exhibition of the work of Nicolas De Staël and came away impressed with the French artist’s abstractions. Although today regarded as perhaps the pre-eminent painter of the male nude of the postwar period, Vaughan’s concurrent interest in landscape painting, inspired by his travels around Britain, Ireland, France, Italy, Greece, Spain and Morocco, is such that almost half of his extant paintings are landscapes.

By the first half of the 1950s Vaughan was exhibiting regularly at the Lefevre, Redfern and Leicester Galleries in London, and also at Durlacher gallery in New York. In his later years he taught at the Central School of Art and the Slade School of Art, as well as at Iowa State University in America. The peak of Vaughan’s success came in the 1950s and early 1960s, culminating in a major retrospective exhibition of his work, numbering over three hundred paintings, gouaches and drawings, at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London in 1962. The exhibition was a critical success, one reviewer commenting that ‘One remains in no doubt, within five minutes of entering the retrospective exhibition of paintings and drawings by Keith Vaughan, that one is in the presence of a very considerable artist and a very consistent one.’ Not long after this, however, the artist began to fear that his works were being overshadowed by newer movements in art, notably British Pop Art and Abstract Expressionism, though he continued to have regular exhibitions in galleries in Britain and America, notably at the Waddington Galleries in London. His health began to worsen and he underwent a series of major operations that sapped him of his energy and exacerbated a tendency to depression. On the morning of 4 November 1977, suffering from terminal cancer, Vaughan committed suicide with a fatal overdose of pills, writing in his journal to the very end.

Provenance

Austin/Desmond Fine Art, Ascot, in 1987

J. Brooks Buxton, London

Anthony Hepworth Fine Art, Bath, in c.1995

Private collection

Anonymous sale, London, Christie’s, 21 November 2007, lot 209.

J. Brooks Buxton, London

Anthony Hepworth Fine Art, Bath, in c.1995

Private collection

Anonymous sale, London, Christie’s, 21 November 2007, lot 209.

Literature

Keith Vaughan, Journals & drawings 1939-1965, London, 1966, illustrated p.45.