Keith VAUGHAN

(Selsey 1912 - London 1977)

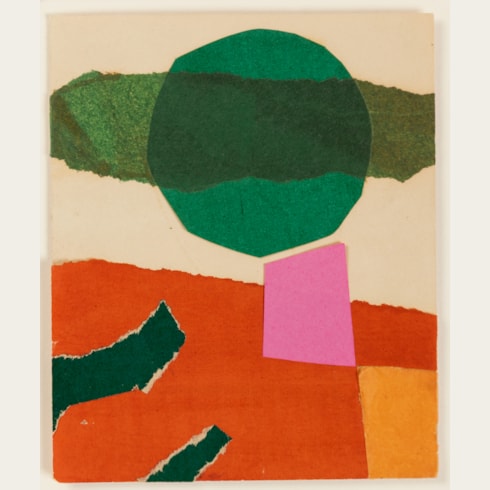

Figure: June 21 1961

Sold

Oil pastel and gouache on thin paper.

Signed Keith Vaughan in pencil and indistinctly dated June 21/ 61 at the lower right.

499 x 365 mm. (19 5/8 x 14 3/8 in.)

Signed Keith Vaughan in pencil and indistinctly dated June 21/ 61 at the lower right.

499 x 365 mm. (19 5/8 x 14 3/8 in.)

A deep, rich blue tonality is a particular characteristic of Keith Vaughan’s works of the 1960s and 1970s. As Andrew Lambirth has pointed out, ‘The emphasis on outline and flat pattern began to change as he developed more of an interest in the plastic properties of oil paint and its formal possibilities. This led in the 1960s to a new fluidity of paint handling and brighter colour. Increasing lucidity was matched by a new excitement frequently bordering on lyricism. Brushwork, rather than drawing, was now the driving force. Colour was used more abstractly, in a seemingly casual way but actually instinctively and with flair, and there was movement apparent.’

Drawn on 21 June 1961, the present sheet is executed in what was, for Vaughan, the relatively new medium of oil pastel. The artist here builds an abstract arrangement of rectangular, tessellated blocks – in shades of cobalt blue, indigo and azure, alongside blacks, browns and greys – around and over the outlines of a standing figure. As has been noted, ‘especially in the later gouaches, Vaughan introduced geometric features such as rectangles and rhomboids, seemingly floating about in space. These characteristic squared-off coloured slabs are woven into the compositional fabric of his gouaches to strengthen their formal construction; it was a fine-tuning formula that helped him achieve pictorial resolution. His precisely calibrated block forms, made with opaque gouache or later with dense coats of oil pastel, supplied flat areas of colour that contrasted with meandering lines and textured surfaces. They also provided Vaughan with an innovative way to suggest pictorial space.’

It was in 1959, during his period of teaching in Iowa, that Vaughan first discovered oil pastels, and he continued to use them for the remainder of his career. He appreciated the density of colour that he could achieve with oil pastels, which could be applied quickly and, unlike chalks or wax crayons, were not fugitive and did not smudge. (‘As they were rare in England, he explained to [friend and fellow artist] Prunella Clough that they were ‘waterproof, impervious to everything, can be rolled, stamped on, eaten.’’) As the Vaughan scholar Gerard Hastings has noted, oil pastels ‘came in a rainbow range of colours, and were subtler and more succulent than their semi-transparent waxy cousins; [Vaughan] found them to be a highly obliging medium. He eagerly exploited their pictorial value…Oil pastels could create broad slabs of colour with little effort or, after using a pencil sharpener on them, could tease out fine contours and other delicate details…Vaughan could significantly enhance the impact of a gouache by the application of a shrewdly placed block of vibrant colour or a pulsating hue that would sing out from the painted surface.’ When Vaughan exhibited his oil pastels in London, after his return from America, they were offered for sale at prices between £30 and £40 apiece.

Lent by the artist, the present sheet was one of eighteen oil pastels selected by Vaughan for inclusion in the major retrospective of his work at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1962. However, due to the limitations of space, many of the works he had chosen could not be hung, and were instead shown at the Matthiesen Gallery in London later the same year. A stylistically comparable figure drawing in oil pastel, dated 23 April 1961, appeared at auction in London in 2011, while another oil pastel of a Standing Figure in a Landscape of 1962 was formerly in the noted collection of the artist’s friend and patron John Ball and appeared on the art market in 2012.

As the poet and writer Stephen Spender has opined, ‘the real drama of Vaughan’s paintings is (to me at all events) in his human figures. Alone of modern painters he has taken up and developed the themes of nudes in Cezanne’s studies of bathers. These human beings remind us that we call branches ‘limbs’, and in the sunlight out of doors they often have the quality of displaced trees with the bark stripped off. Whereas in Cézanne the flesh seems far less sensual than, say, in a painting of an apple, in Vaughan’s paintings it has an almost magnetic – certainly metallic – attraction. At the same time it is colour and form that is beautiful in his figures, never the human subject itself. The flesh is sad and grey and greeny-bluish but through a metamorphosis of colour and form it attains to beauty beyond its fleshiness.’

The first owner of the present sheet was Humphrey Whitbread (1912-2000), of the Whitbread brewing family, who assembled a number of works by Keith Vaughan alongside a fine collection of Georgian and Regency furniture, much of which was kept at his home, Howard’s House in the village of Cardington in Bedfordshire, near the Whitbread family estate at Southill. This drawing was later acquired by another collector of Vaughan’s works, the American author, poet and English professor John Weston (1932-2023).

Drawn on 21 June 1961, the present sheet is executed in what was, for Vaughan, the relatively new medium of oil pastel. The artist here builds an abstract arrangement of rectangular, tessellated blocks – in shades of cobalt blue, indigo and azure, alongside blacks, browns and greys – around and over the outlines of a standing figure. As has been noted, ‘especially in the later gouaches, Vaughan introduced geometric features such as rectangles and rhomboids, seemingly floating about in space. These characteristic squared-off coloured slabs are woven into the compositional fabric of his gouaches to strengthen their formal construction; it was a fine-tuning formula that helped him achieve pictorial resolution. His precisely calibrated block forms, made with opaque gouache or later with dense coats of oil pastel, supplied flat areas of colour that contrasted with meandering lines and textured surfaces. They also provided Vaughan with an innovative way to suggest pictorial space.’

It was in 1959, during his period of teaching in Iowa, that Vaughan first discovered oil pastels, and he continued to use them for the remainder of his career. He appreciated the density of colour that he could achieve with oil pastels, which could be applied quickly and, unlike chalks or wax crayons, were not fugitive and did not smudge. (‘As they were rare in England, he explained to [friend and fellow artist] Prunella Clough that they were ‘waterproof, impervious to everything, can be rolled, stamped on, eaten.’’) As the Vaughan scholar Gerard Hastings has noted, oil pastels ‘came in a rainbow range of colours, and were subtler and more succulent than their semi-transparent waxy cousins; [Vaughan] found them to be a highly obliging medium. He eagerly exploited their pictorial value…Oil pastels could create broad slabs of colour with little effort or, after using a pencil sharpener on them, could tease out fine contours and other delicate details…Vaughan could significantly enhance the impact of a gouache by the application of a shrewdly placed block of vibrant colour or a pulsating hue that would sing out from the painted surface.’ When Vaughan exhibited his oil pastels in London, after his return from America, they were offered for sale at prices between £30 and £40 apiece.

Lent by the artist, the present sheet was one of eighteen oil pastels selected by Vaughan for inclusion in the major retrospective of his work at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1962. However, due to the limitations of space, many of the works he had chosen could not be hung, and were instead shown at the Matthiesen Gallery in London later the same year. A stylistically comparable figure drawing in oil pastel, dated 23 April 1961, appeared at auction in London in 2011, while another oil pastel of a Standing Figure in a Landscape of 1962 was formerly in the noted collection of the artist’s friend and patron John Ball and appeared on the art market in 2012.

As the poet and writer Stephen Spender has opined, ‘the real drama of Vaughan’s paintings is (to me at all events) in his human figures. Alone of modern painters he has taken up and developed the themes of nudes in Cezanne’s studies of bathers. These human beings remind us that we call branches ‘limbs’, and in the sunlight out of doors they often have the quality of displaced trees with the bark stripped off. Whereas in Cézanne the flesh seems far less sensual than, say, in a painting of an apple, in Vaughan’s paintings it has an almost magnetic – certainly metallic – attraction. At the same time it is colour and form that is beautiful in his figures, never the human subject itself. The flesh is sad and grey and greeny-bluish but through a metamorphosis of colour and form it attains to beauty beyond its fleshiness.’

The first owner of the present sheet was Humphrey Whitbread (1912-2000), of the Whitbread brewing family, who assembled a number of works by Keith Vaughan alongside a fine collection of Georgian and Regency furniture, much of which was kept at his home, Howard’s House in the village of Cardington in Bedfordshire, near the Whitbread family estate at Southill. This drawing was later acquired by another collector of Vaughan’s works, the American author, poet and English professor John Weston (1932-2023).

Born in Sussex, Keith Vaughan moved with his family to North London around the start of the First World War. He showed a gift for the arts from a very young age, earning a Royal Drawing Society certificate at the age of seven, but received almost no formal artistic education and was mostly self-taught. While at boarding school, Vaughan was given special entitlements to study art, since he was the first student to specialize in it, and it was at the Christ’s Hospital school that he mounted his first exhibition of landscapes. At the age of nineteen, Vaughan began work as a trainee in the art department of an advertising firm, where he remained until just before the start of the Second World War. In 1939 he left the firm and moved to the country, intending to paint for a year; this would be the first consistent time Vaughan would spend as a fine artist since his school days. It was also at around this time that he began keeping a written journal, a practice he maintained until his death, and which eventually amounted to some 750,000 words contained in sixty-one volumes.

During the Second World War, Vaughan declared himself a conscientious objector, and was conscripted into the Non-Combatant Corps (NCC), working as a labourer in Wiltshire and Derbyshire. It was during the war that, through the collector Peter Watson, Vaughan came into contact with such contemporaries such as Graham Sutherland and John Minton, both of whom were to be highly influential on the artist’s developing career, as well as John Craxton. It was also during this time that Vaughan began exhibiting his work, first in a group exhibition of War Artists organized by Kenneth Clark at the National Gallery in London in 1943, followed by a small show of drawings – of army subjects, landscapes and figures – at the Alex Reid & Lefevre Gallery in London at the end of the following year.

After the war Vaughan began to work consistently in oil paint. Leaving the army in 1946, he taught part-time at the Camberwell School of Art and held the first exhibition of his paintings and gouaches at the Lefevre Gallery. The same year he moved into a house and studio in Maida Vale that he shared with Minton, working alongside him for the next six years. Vaughan’s postwar style was very different from that of the 1930s, with the artist focussing on oil painting and more fully finished compositions and turning away from the English Neo-Romanticism of his earlier work. He also produced designs for book jackets, magazine illustrations and advertisements, and received an important commission for a fifty-foot-long mural for the Dome of Discovery, a temporary building erected on the South Bank for the 1951 Festival of Britain, which is now lost. Focussing on the nude male form, Vaughan’s work also became more abstract; in 1952 he saw an exhibition of the work of Nicolas De Staël and came away impressed with the French artist’s abstractions. Although today regarded as perhaps the pre-eminent painter of the male nude of the postwar period, Vaughan’s concurrent interest in landscape painting, inspired by his travels around Britain, Ireland, France, Italy, Greece, Spain and Morocco, is such that almost half of his extant paintings are landscapes.

By the first half of the 1950s Vaughan was exhibiting regularly at the Lefevre, Redfern and Leicester Galleries in London, and also at Durlacher gallery in New York. In his later years he taught at the Central School of Art and the Slade School of Art, as well as at Iowa State University in America. The peak of Vaughan’s success came in the 1950s and early 1960s, culminating in a major retrospective exhibition of his work, numbering over three hundred paintings, gouaches and drawings, at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London in 1962. The exhibition was a critical success, one reviewer commenting that ‘One remains in no doubt, within five minutes of entering the retrospective exhibition of paintings and drawings by Keith Vaughan, that one is in the presence of a very considerable artist and a very consistent one.’ Not long after this, however, the artist began to fear that his works were being overshadowed by newer movements in art, notably British Pop Art and Abstract Expressionism, though he continued to have regular exhibitions in galleries in Britain and America, notably at the Waddington Galleries in London. His health began to worsen and he underwent a series of major operations that sapped him of his energy and exacerbated a tendency to depression. On the morning of 4 November 1977, suffering from terminal cancer, Vaughan committed suicide with a fatal overdose of pills, writing in his journal to the very end.

During the Second World War, Vaughan declared himself a conscientious objector, and was conscripted into the Non-Combatant Corps (NCC), working as a labourer in Wiltshire and Derbyshire. It was during the war that, through the collector Peter Watson, Vaughan came into contact with such contemporaries such as Graham Sutherland and John Minton, both of whom were to be highly influential on the artist’s developing career, as well as John Craxton. It was also during this time that Vaughan began exhibiting his work, first in a group exhibition of War Artists organized by Kenneth Clark at the National Gallery in London in 1943, followed by a small show of drawings – of army subjects, landscapes and figures – at the Alex Reid & Lefevre Gallery in London at the end of the following year.

After the war Vaughan began to work consistently in oil paint. Leaving the army in 1946, he taught part-time at the Camberwell School of Art and held the first exhibition of his paintings and gouaches at the Lefevre Gallery. The same year he moved into a house and studio in Maida Vale that he shared with Minton, working alongside him for the next six years. Vaughan’s postwar style was very different from that of the 1930s, with the artist focussing on oil painting and more fully finished compositions and turning away from the English Neo-Romanticism of his earlier work. He also produced designs for book jackets, magazine illustrations and advertisements, and received an important commission for a fifty-foot-long mural for the Dome of Discovery, a temporary building erected on the South Bank for the 1951 Festival of Britain, which is now lost. Focussing on the nude male form, Vaughan’s work also became more abstract; in 1952 he saw an exhibition of the work of Nicolas De Staël and came away impressed with the French artist’s abstractions. Although today regarded as perhaps the pre-eminent painter of the male nude of the postwar period, Vaughan’s concurrent interest in landscape painting, inspired by his travels around Britain, Ireland, France, Italy, Greece, Spain and Morocco, is such that almost half of his extant paintings are landscapes.

By the first half of the 1950s Vaughan was exhibiting regularly at the Lefevre, Redfern and Leicester Galleries in London, and also at Durlacher gallery in New York. In his later years he taught at the Central School of Art and the Slade School of Art, as well as at Iowa State University in America. The peak of Vaughan’s success came in the 1950s and early 1960s, culminating in a major retrospective exhibition of his work, numbering over three hundred paintings, gouaches and drawings, at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London in 1962. The exhibition was a critical success, one reviewer commenting that ‘One remains in no doubt, within five minutes of entering the retrospective exhibition of paintings and drawings by Keith Vaughan, that one is in the presence of a very considerable artist and a very consistent one.’ Not long after this, however, the artist began to fear that his works were being overshadowed by newer movements in art, notably British Pop Art and Abstract Expressionism, though he continued to have regular exhibitions in galleries in Britain and America, notably at the Waddington Galleries in London. His health began to worsen and he underwent a series of major operations that sapped him of his energy and exacerbated a tendency to depression. On the morning of 4 November 1977, suffering from terminal cancer, Vaughan committed suicide with a fatal overdose of pills, writing in his journal to the very end.

Provenance

Humphrey Whitbread, Southill Park, Southill, Bedfordshire and Howard’s House, Cardington, Bedfordshire

John Weston, Palm Desert, California

Private collection, Los Angeles

Private collection.

John Weston, Palm Desert, California

Private collection, Los Angeles

Private collection.

Exhibition

London, Whitechapel Gallery, and elsewhere, Keith Vaughan: retrospective exhibition, March-April 1962, no.319 (lent by the artist); London, Matthiesen Gallery, Keith Vaughan: Paintings and Drawings 1937-1962, 1962, no.74.