Keith VAUGHAN

(Selsey 1912 - London 1977)

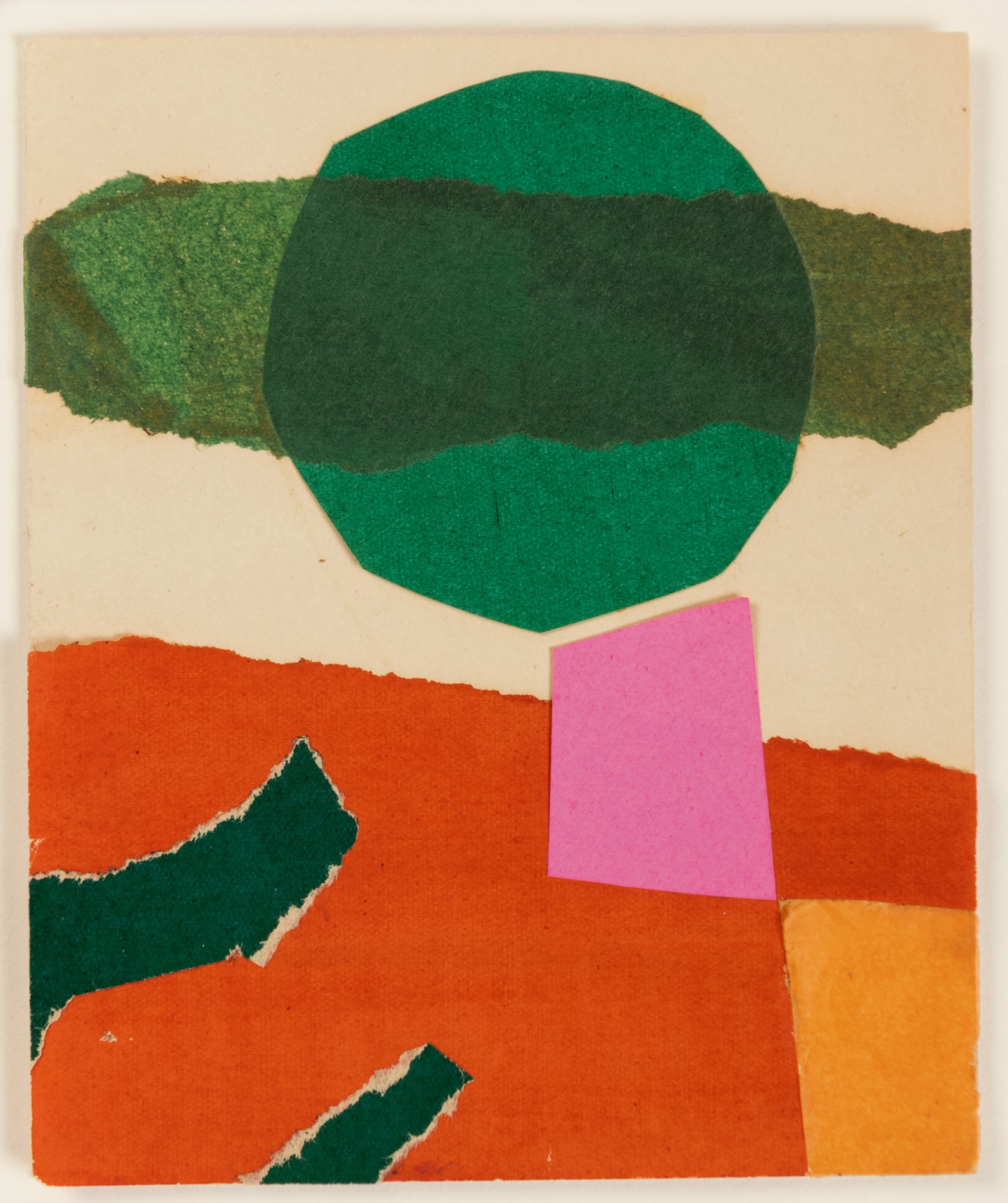

Landscape with Sunset

Paper collage on one side of a folded white card.

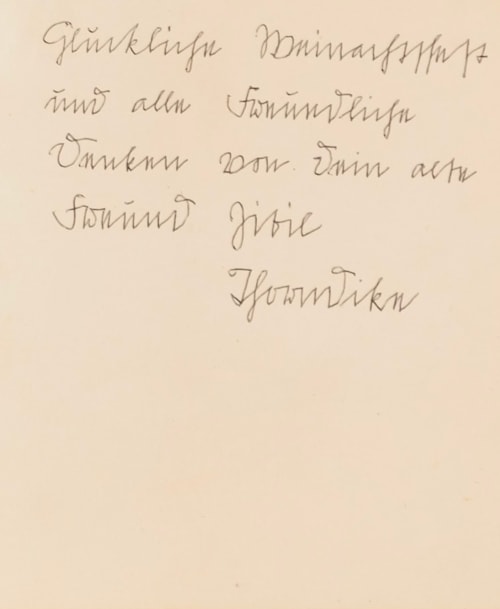

Inscribed by the artist in German 'Glückliche Weinachtsfest / und alle freundliche / Denken von dein alte / Freund Jivie(?) / Ifawndike (?)' in pencil on the inside of the folded card.

147 x 121 mm. (5 3/4 x 4 3/4 in.)

Inscribed by the artist in German 'Glückliche Weinachtsfest / und alle freundliche / Denken von dein alte / Freund Jivie(?) / Ifawndike (?)' in pencil on the inside of the folded card.

147 x 121 mm. (5 3/4 x 4 3/4 in.)

Throughout much of his mature career Keith Vaughan’s work embraced both figuration and abstraction. In 1953 he saw an exhibition of the work of Nicolas De Staël and came away impressed with the French artist’s abstractions. Yet Vaughan never saw himself as a purely abstract painter, stating that ‘Painting has always been a representational art and if you remove the representational element from it, as a great many painters do, then you simply impoverish it. Even if you can’t see the representational element in the finished product it must be there to begin with; for me painting which has not got a representational element in it hardly goes beyond the point of design.’

Collaged compositions by Vaughan are quite rare. The present sheet, which can likely be dated to the first half of the 1970s, was sent as a Christmas greeting card to the artist’s friend Klaus Peter Adam (1929-2019), a German-born filmmaker and television producer. Born in Berlin, Peter Adam settled in England at the age of thirty and joined the BBC in the late 1960s, becoming a British citizen in 1965. He worked at the BBC for twenty-two years, during which he made over a hundred documentaries on arts and culture, and also published a biography of the designer and architect Eileen Gray. Adam was a close friend of several artists, notably Vaughan and Prunella Clough, and carried on an extensive correspondence with both. He had been introduced to Vaughan in 1958 and the two remained close until the artist’s death.

As Peter Adam recalled in his autobiography, published in 1995, ‘My other painter friend was Keith Vaughan, a stocky, slightly balding man of about fifty. Hailed in the 1950s as one of the great white hopes of British painting, his fame had been slightly eclipsed by the younger generation. We drove in an old and immaculate Morris Minor to the country or we spend the evening in his London home reading Rilke or Rimbaud, whose verses he had illustrated. He spoke very good French and German, having worked as an interpreter for German prisoners during the war…Despite his success he had little confidence in himself. He was very critical, often too critical for many: his wide knowledge of literature, music and the visual arts, as well as an acute sense of observation, often made him harsh in his judgement of others. Everything about Keith – his manners, his flat and his appearance – was orderly in an almost old-maidish way, but underneath ran a dangerous self-destructive current...It became my role to free him from some of his strictures and to make him laugh…People writing about Vaughan have always concentrated on his darker side, but in over twenty years I saw much light and a great capacity for friendship, even laughter. He could be very funny and he had great wit.’ As Adam wrote elsewhere of Vaughan, ‘a melancholic dignity surrounded everything he did [but] the man I learned to love and to value was also a man of many joys and much humour.’ After Vaughan’s death in 1977, Adam served as one of the executors of his estate, and also curated a number of exhibitions of his work.

In his private journals, Vaughan usually refers to Adam by his initials KP or KPA, and in one reference to him, written in 1976, notes: ‘Long letter from KPA about death having some meaning & living beautifully & how much he loves me. A letter which must have been difficult to write & acutely embarrassing to read. Poor dear, he tries so hard & means well but emotionally we are on different wave lengths.’

Collaged compositions by Vaughan are quite rare. The present sheet, which can likely be dated to the first half of the 1970s, was sent as a Christmas greeting card to the artist’s friend Klaus Peter Adam (1929-2019), a German-born filmmaker and television producer. Born in Berlin, Peter Adam settled in England at the age of thirty and joined the BBC in the late 1960s, becoming a British citizen in 1965. He worked at the BBC for twenty-two years, during which he made over a hundred documentaries on arts and culture, and also published a biography of the designer and architect Eileen Gray. Adam was a close friend of several artists, notably Vaughan and Prunella Clough, and carried on an extensive correspondence with both. He had been introduced to Vaughan in 1958 and the two remained close until the artist’s death.

As Peter Adam recalled in his autobiography, published in 1995, ‘My other painter friend was Keith Vaughan, a stocky, slightly balding man of about fifty. Hailed in the 1950s as one of the great white hopes of British painting, his fame had been slightly eclipsed by the younger generation. We drove in an old and immaculate Morris Minor to the country or we spend the evening in his London home reading Rilke or Rimbaud, whose verses he had illustrated. He spoke very good French and German, having worked as an interpreter for German prisoners during the war…Despite his success he had little confidence in himself. He was very critical, often too critical for many: his wide knowledge of literature, music and the visual arts, as well as an acute sense of observation, often made him harsh in his judgement of others. Everything about Keith – his manners, his flat and his appearance – was orderly in an almost old-maidish way, but underneath ran a dangerous self-destructive current...It became my role to free him from some of his strictures and to make him laugh…People writing about Vaughan have always concentrated on his darker side, but in over twenty years I saw much light and a great capacity for friendship, even laughter. He could be very funny and he had great wit.’ As Adam wrote elsewhere of Vaughan, ‘a melancholic dignity surrounded everything he did [but] the man I learned to love and to value was also a man of many joys and much humour.’ After Vaughan’s death in 1977, Adam served as one of the executors of his estate, and also curated a number of exhibitions of his work.

In his private journals, Vaughan usually refers to Adam by his initials KP or KPA, and in one reference to him, written in 1976, notes: ‘Long letter from KPA about death having some meaning & living beautifully & how much he loves me. A letter which must have been difficult to write & acutely embarrassing to read. Poor dear, he tries so hard & means well but emotionally we are on different wave lengths.’

Born in Sussex, Keith Vaughan moved with his family to North London around the start of the First World War. He showed a gift for the arts from a very young age, earning a Royal Drawing Society certificate at the age of seven, but received almost no formal artistic education and was mostly self-taught. While at boarding school, Vaughan was given special entitlements to study art, since he was the first student to specialize in it, and it was at the Christ’s Hospital school that he mounted his first exhibition of landscapes. At the age of nineteen, Vaughan began work as a trainee in the art department of an advertising firm, where he remained until just before the start of the Second World War. In 1939 he left the firm and moved to the country, intending to paint for a year; this would be the first consistent time Vaughan would spend as a fine artist since his school days. It was also at around this time that he began keeping a written journal, a practice he maintained until his death, and which eventually amounted to some 750,000 words contained in sixty-one volumes.

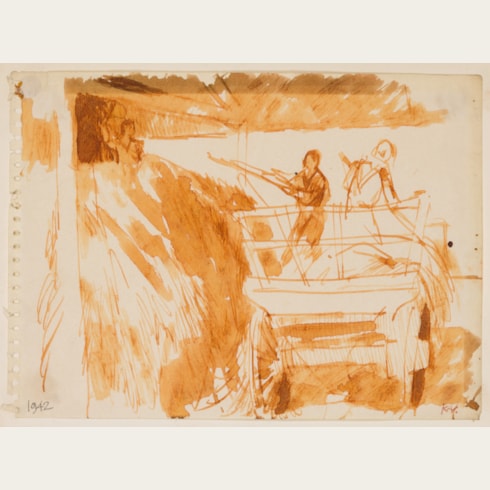

During the Second World War, Vaughan declared himself a conscientious objector, and was conscripted into the Non-Combatant Corps (NCC), working as a labourer in Wiltshire and Derbyshire. It was during the war that, through the collector Peter Watson, Vaughan came into contact with such contemporaries such as Graham Sutherland and John Minton, both of whom were to be highly influential on the artist’s developing career, as well as John Craxton. It was also during this time that Vaughan began exhibiting his work, first in a group exhibition of War Artists organized by Kenneth Clark at the National Gallery in London in 1943, followed by a small show of drawings – of army subjects, landscapes and figures – at the Alex Reid & Lefevre Gallery in London at the end of the following year.

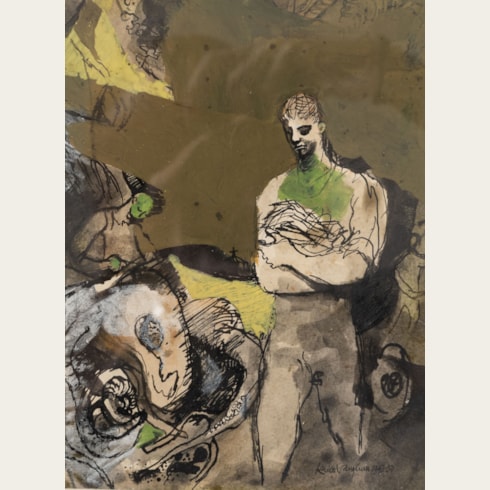

After the war Vaughan began to work consistently in oil paint. Leaving the army in 1946, he taught part-time at the Camberwell School of Art and held the first exhibition of his paintings and gouaches at the Lefevre Gallery. The same year he moved into a house and studio in Maida Vale that he shared with Minton, working alongside him for the next six years. Vaughan’s postwar style was very different from that of the 1930s, with the artist focussing on oil painting and more fully finished compositions and turning away from the English Neo-Romanticism of his earlier work. He also produced designs for book jackets, magazine illustrations and advertisements, and received an important commission for a fifty-foot-long mural for the Dome of Discovery, a temporary building erected on the South Bank for the 1951 Festival of Britain, which is now lost. Focussing on the nude male form, Vaughan’s work also became more abstract; in 1952 he saw an exhibition of the work of Nicolas De Staël and came away impressed with the French artist’s abstractions. Although today regarded as perhaps the pre-eminent painter of the male nude of the postwar period, Vaughan’s concurrent interest in landscape painting, inspired by his travels around Britain, Ireland, France, Italy, Greece, Spain and Morocco, is such that almost half of his extant paintings are landscapes.

By the first half of the 1950s Vaughan was exhibiting regularly at the Lefevre, Redfern and Leicester Galleries in London, and also at Durlacher gallery in New York. In his later years he taught at the Central School of Art and the Slade School of Art, as well as at Iowa State University in America. The peak of Vaughan’s success came in the 1950s and early 1960s, culminating in a major retrospective exhibition of his work, numbering over three hundred paintings, gouaches and drawings, at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London in 1962. The exhibition was a critical success, one reviewer commenting that ‘One remains in no doubt, within five minutes of entering the retrospective exhibition of paintings and drawings by Keith Vaughan, that one is in the presence of a very considerable artist and a very consistent one.’ Not long after this, however, the artist began to fear that his works were being overshadowed by newer movements in art, notably British Pop Art and Abstract Expressionism, though he continued to have regular exhibitions in galleries in Britain and America, notably at the Waddington Galleries in London. His health began to worsen and he underwent a series of major operations that sapped him of his energy and exacerbated a tendency to depression. On the morning of 4 November 1977, suffering from terminal cancer, Vaughan committed suicide with a fatal overdose of pills, writing in his journal to the very end.

During the Second World War, Vaughan declared himself a conscientious objector, and was conscripted into the Non-Combatant Corps (NCC), working as a labourer in Wiltshire and Derbyshire. It was during the war that, through the collector Peter Watson, Vaughan came into contact with such contemporaries such as Graham Sutherland and John Minton, both of whom were to be highly influential on the artist’s developing career, as well as John Craxton. It was also during this time that Vaughan began exhibiting his work, first in a group exhibition of War Artists organized by Kenneth Clark at the National Gallery in London in 1943, followed by a small show of drawings – of army subjects, landscapes and figures – at the Alex Reid & Lefevre Gallery in London at the end of the following year.

After the war Vaughan began to work consistently in oil paint. Leaving the army in 1946, he taught part-time at the Camberwell School of Art and held the first exhibition of his paintings and gouaches at the Lefevre Gallery. The same year he moved into a house and studio in Maida Vale that he shared with Minton, working alongside him for the next six years. Vaughan’s postwar style was very different from that of the 1930s, with the artist focussing on oil painting and more fully finished compositions and turning away from the English Neo-Romanticism of his earlier work. He also produced designs for book jackets, magazine illustrations and advertisements, and received an important commission for a fifty-foot-long mural for the Dome of Discovery, a temporary building erected on the South Bank for the 1951 Festival of Britain, which is now lost. Focussing on the nude male form, Vaughan’s work also became more abstract; in 1952 he saw an exhibition of the work of Nicolas De Staël and came away impressed with the French artist’s abstractions. Although today regarded as perhaps the pre-eminent painter of the male nude of the postwar period, Vaughan’s concurrent interest in landscape painting, inspired by his travels around Britain, Ireland, France, Italy, Greece, Spain and Morocco, is such that almost half of his extant paintings are landscapes.

By the first half of the 1950s Vaughan was exhibiting regularly at the Lefevre, Redfern and Leicester Galleries in London, and also at Durlacher gallery in New York. In his later years he taught at the Central School of Art and the Slade School of Art, as well as at Iowa State University in America. The peak of Vaughan’s success came in the 1950s and early 1960s, culminating in a major retrospective exhibition of his work, numbering over three hundred paintings, gouaches and drawings, at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London in 1962. The exhibition was a critical success, one reviewer commenting that ‘One remains in no doubt, within five minutes of entering the retrospective exhibition of paintings and drawings by Keith Vaughan, that one is in the presence of a very considerable artist and a very consistent one.’ Not long after this, however, the artist began to fear that his works were being overshadowed by newer movements in art, notably British Pop Art and Abstract Expressionism, though he continued to have regular exhibitions in galleries in Britain and America, notably at the Waddington Galleries in London. His health began to worsen and he underwent a series of major operations that sapped him of his energy and exacerbated a tendency to depression. On the morning of 4 November 1977, suffering from terminal cancer, Vaughan committed suicide with a fatal overdose of pills, writing in his journal to the very end.

Provenance

Given by the artist to (Klaus) Peter Adam, London and Sèvres

Thence by descent

Sale (‘Property from the Collection of the Late Peter Adam’), London, Chiswick Auctions, 26 March 2024, part of lot 30

Harry Moore-Gwyn, London and Gloucestershire.

Thence by descent

Sale (‘Property from the Collection of the Late Peter Adam’), London, Chiswick Auctions, 26 March 2024, part of lot 30

Harry Moore-Gwyn, London and Gloucestershire.