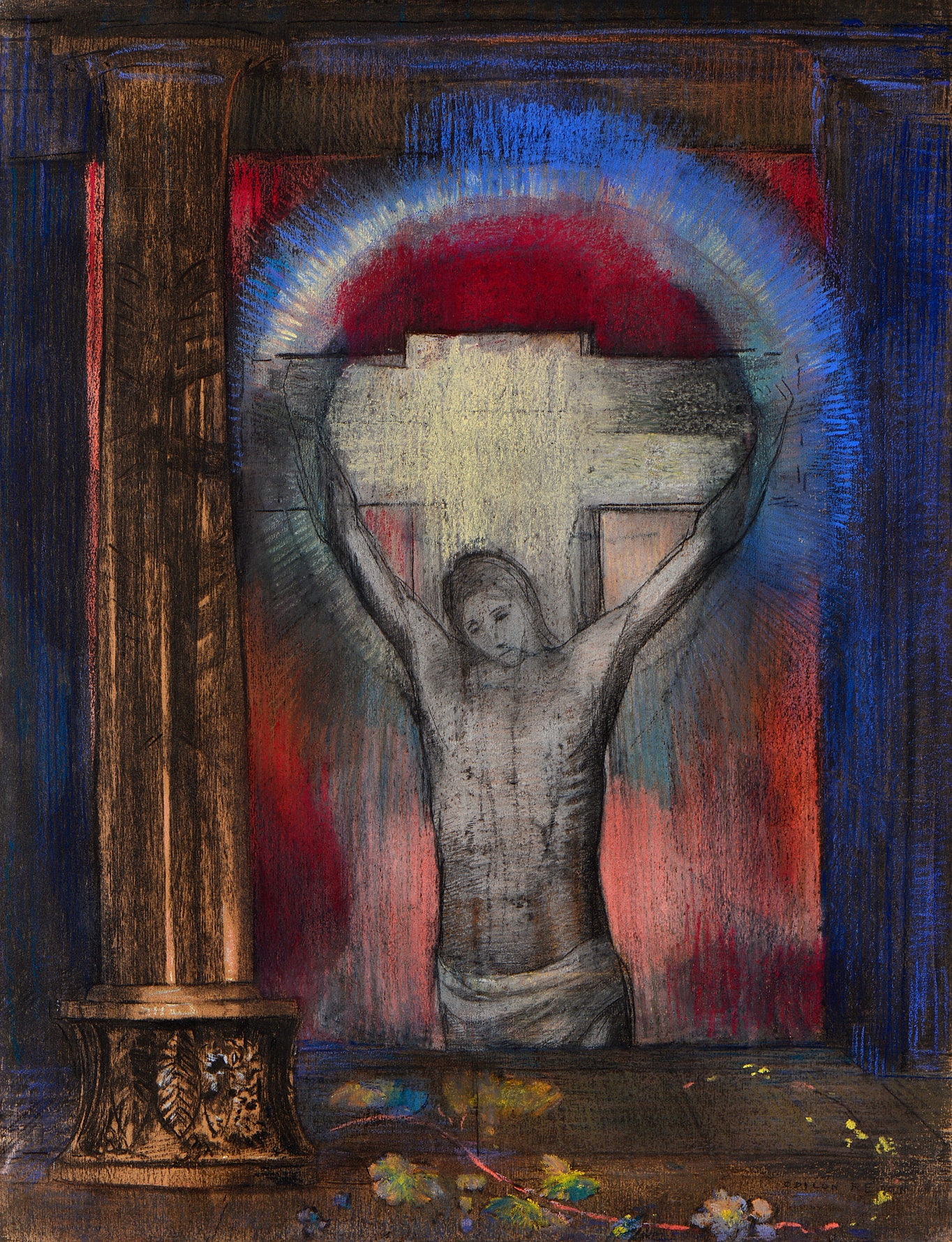

Odilon REDON

(Bordeaux 1840 - Paris 1916)

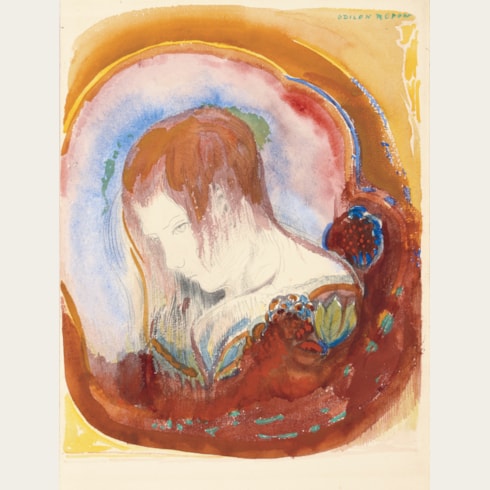

Christ on the Cross

Sold

Pastel and chalk on paper, laid down on board.

Signed ODILON REDON at the lower right.

488 x 372 mm. (19 1/4 x 14 5/8 in.)

Signed ODILON REDON at the lower right.

488 x 372 mm. (19 1/4 x 14 5/8 in.)

Odilon Redon’s pastels account for some of his finest works. In an 1897 letter to his close friend Andries Bonger, the artist wrote of his use of the medium: ‘The pastel, in fact, gives me support, materially and morally, it has rejuvenated me. I work with it, without getting tired. It has led me to paint; in looking at the work that I have just done, I am not without hope of transferring to canvas certain ideas a little later.’1 As the Redon scholar Roseline Bacou has noted, ‘In but a few years, Redon had completely mastered the technical demands of pastel...Up to the end of his life, the pastel would be a particularly special means of expression for Redon.’

The figure of Christ was a recurring theme in Redon’s oeuvre between 1895 and around 1910. As Bacou notes, ‘The pastels of 1895-1899 are dominated by the figure of Christ: the Sacred Heart with a colored flame at the center of his chest; the Christ of Silence, with a finger upon his lips; Christ with the red thorns; Christ on the Cross...The use of such religious imagery, however, was not related to a strict belief in religious doctrine on Redon’s part...In the pastels executed during this period, the intensity of the colors echoes the ardent spirituality of the themes.’

The present sheet has remained very little known to most scholars, having been in a Japanese collection since at least the early 1950’s. The work was published for the first time by Klaus Berger in 1964, and again the following year in an article describing works by Redon in Japanese collections, in which he noted that ‘However strange may seem the presence of Christ in the collection of a non-Christian country, the fact confirms once more that the art of Redon was accepted by the Japanese as a link between East and West, and they, with their usual zeal, wished to know all its aspects.’ The present pastel has never previously been exhibited outside Japan, where it was last shown in 1989. After more than fifty years in Japanese collections, The Crucified Christ was sold at auction in New York in 2002, when it entered a private collection in which it has remained ever since.

When the present pastel was last exhibited in public, twenty-five years ago in Japan, the author of the catalogue entry noted of it: ‘For some reason, this Christ on the Cross is set inside a room with no exit. It is a Redon pastel which we can be proud to have in Japan...The image of Christ appears, emitting light, behind a pillar in a dark room, this dense interior contains the deep spirituality characteristic of Redon’s religious pictures.’ In superb condition, the present work has retained all of its freshness and richness of colour, and as such presents a consummate example of Redon’s pastel technique.

Alec Wildenstein’s catalogue raisonné of Redon’s oeuvre lists a total of just fifteen depictions of the subject of Christ on the cross, including two small paintings, five pastels and eight drawings in chalk, pencil or charcoal.

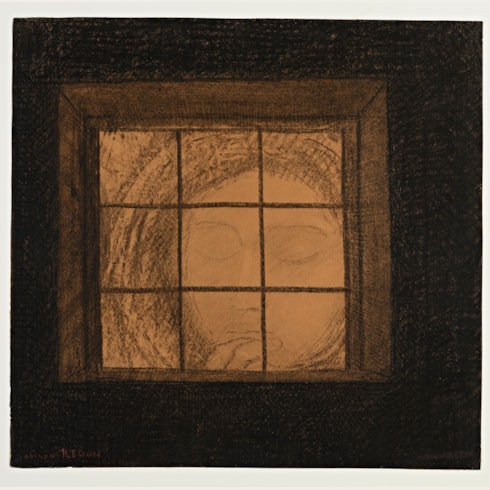

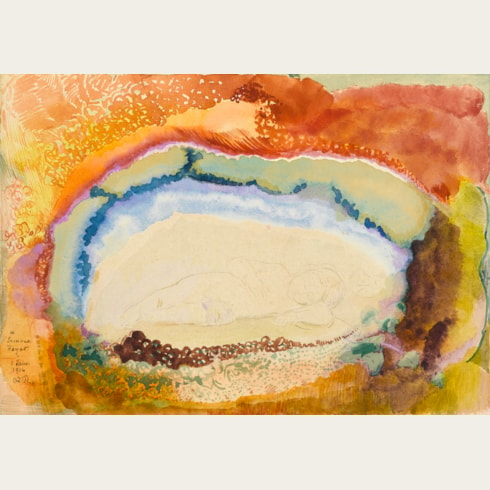

Among the handful of pastel drawings of Christ on the Cross by Redon is a large example, showing just the head and upper torso of Christ, in the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten in Antwerp and a Crucifixion in the E. G. Bührle Collection in Zurich, as well as another, smaller pastel sold at auction in London in 1989.

The figure of Christ was a recurring theme in Redon’s oeuvre between 1895 and around 1910. As Bacou notes, ‘The pastels of 1895-1899 are dominated by the figure of Christ: the Sacred Heart with a colored flame at the center of his chest; the Christ of Silence, with a finger upon his lips; Christ with the red thorns; Christ on the Cross...The use of such religious imagery, however, was not related to a strict belief in religious doctrine on Redon’s part...In the pastels executed during this period, the intensity of the colors echoes the ardent spirituality of the themes.’

The present sheet has remained very little known to most scholars, having been in a Japanese collection since at least the early 1950’s. The work was published for the first time by Klaus Berger in 1964, and again the following year in an article describing works by Redon in Japanese collections, in which he noted that ‘However strange may seem the presence of Christ in the collection of a non-Christian country, the fact confirms once more that the art of Redon was accepted by the Japanese as a link between East and West, and they, with their usual zeal, wished to know all its aspects.’ The present pastel has never previously been exhibited outside Japan, where it was last shown in 1989. After more than fifty years in Japanese collections, The Crucified Christ was sold at auction in New York in 2002, when it entered a private collection in which it has remained ever since.

When the present pastel was last exhibited in public, twenty-five years ago in Japan, the author of the catalogue entry noted of it: ‘For some reason, this Christ on the Cross is set inside a room with no exit. It is a Redon pastel which we can be proud to have in Japan...The image of Christ appears, emitting light, behind a pillar in a dark room, this dense interior contains the deep spirituality characteristic of Redon’s religious pictures.’ In superb condition, the present work has retained all of its freshness and richness of colour, and as such presents a consummate example of Redon’s pastel technique.

Alec Wildenstein’s catalogue raisonné of Redon’s oeuvre lists a total of just fifteen depictions of the subject of Christ on the cross, including two small paintings, five pastels and eight drawings in chalk, pencil or charcoal.

Among the handful of pastel drawings of Christ on the Cross by Redon is a large example, showing just the head and upper torso of Christ, in the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten in Antwerp and a Crucifixion in the E. G. Bührle Collection in Zurich, as well as another, smaller pastel sold at auction in London in 1989.

At a very young age, Odilon Redon was sent to live with an old uncle at Peyrelebade, a vineyard and estate surrounded by an abandoned park in a barren area of the Médoc region, northwest of Bordeaux. Here the young boy, who suffered from frail health and epilepsy, was to spend much of his childhood in relative solitude. Indeed, it was not until he was eleven that he was sent to school in Bordeaux, where at fifteen he began to take drawing classes. The most important influence on the young artist was Rodolphe Bresdin, whose studio in Bordeaux he frequented, and who was to prove decisive on his artistic development. It was from Bresdin, for example, that Redon learned the techniques of etching and lithography. Nevertheless, for most of his career Redon worked in something of an artistic vacuum, aware of the work of his contemporaries but generally preferring to follow his own path. His drawings and prints allowed him to express his lifelong penchant for imaginary subject matter, and were dominated by strange and unsettling images of fantastic creatures, disembodied heads and masks, solitary eyes, menacing spiders and other dreamlike forms. For much of the first thirty years of his career Redon worked almost exclusively in black, producing his ‘noirs’ in charcoal and chalk; the drawings he described as ‘mes ombres’, or ‘my shadows’.

It was not until 1881, when he was more than forty years old, that Redon first mounted a small exhibition of his work, to almost complete indifference on the part of critics or the public. The following year, however, a second exhibition of drawings and lithographs brought him to the attention of a number of critics. Redon’s reputation began to grow, and in 1884 he exhibited at the first Salon des Indépendants, which he had helped to organize. Two years later he was invited to show at the eighth and final Impressionist exhibition, and in the same year exhibited with Les XX, a group of avant-garde artists, writers and musicians in Brussels.

Towards the end of the 19th century Redon began to move away from working mainly in charcoal and black chalk in favour of a new emphasis on colour, chiefly using the medium of pastel but also watercolour, oil paint and distemper. Indeed, after about 1900 he seems to have almost completely abandoned working in black and white. Like his noirs, his pastels of floral still lives and portraits were popular with a few collectors, and several were included in exhibitions at Durand-Ruel in 1900, 1903 and 1906, and in subsequent exhibitions of his work in Paris and abroad. Despite this change in direction, however, Redon’s work remained unpopular with the public at large, and it was left to a few enlightened collectors to support the artist in his later years. Nevertheless, an entire room was devoted to Redon at the seminal Armory Show held in New York in 1913, an honour shared by Cezanne, Gauguin, Matisse and Van Gogh.

Provenance

K. Nakagawa collection, Tokyo, by 1954

Anonymous sale (‘Property of a Private Family Collection’), New York, Christie’s, 7 November 2002, lot 118

Private collection, New York, until 2014.

Literature

Klaus Berger, Odilon Redon: Phantasie und Farbe, Cologne, 1964, p.208, no.354a; Klaus Berger, Odilon Redon: Fantasy and Colour, New York, 1965, p.207, no.354a; Klaus Berger, ‘Odilon Redon dans les collections japonaises’, L’Oeil, December 1965, p.33, fig.8 (where dated c.1900); Bijutsu Techo, January 1968, illustrated p.167; Mitsuhiko Kuroé, ‘Odilon Redon dans les collections japonaises – dessin, pastel et peinture à l’huile’, Bulletin Annuel du Musée National d’Art Occidental, No.3, Tokyo, 1969, p.12, no.11; Roseline Bacou, Musée du Louvre: La donation Arï et Suzanne Redon, Paris, 1984, p.17, under no.23; Kunio Motoé, Odilon Redon 1840-1916, exhibition catalogue, Tokyo, 1989, p.147, no.171; Alec Wildenstein, Odilon Redon: Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint et dessiné. Vol.I: Portraits et figures, Paris, 1992, p.207, no.522.

Exhibition

Tokyo, Galerie Kyuryudo, Odilon Redon, 1954; Kyoto, Municipal Museum of Art, Exposition des chefs-d’oeuvre occidentaux, 1957; Kamakura, Kanagawa Museum of Modern Art, Exposition de Odilon Redon, 1973, no.22; Tokyo, National Museum of Modern Art, and elsewhere, Odilon Redon 1840-1916, 1989, no.171.