Odilon REDON

(Bordeaux 1840 - Paris 1916)

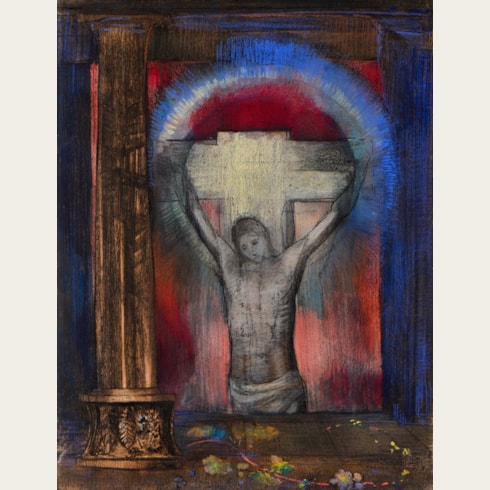

A Face at a Window

Sold

Charcoal.

Signed ODILON REDON in red ink twice, at the lower left and lower right.

357 x 368 mm. (14 x 14 1/2 in.)

Signed ODILON REDON in red ink twice, at the lower left and lower right.

357 x 368 mm. (14 x 14 1/2 in.)

In a well-known letter, written in 1894 and published in L’Art Moderne the same year, Odilon Redon recalled his discovery of charcoal as a drawing medium: ‘Around 1875 my inspiration came only in crayon, in charcoal, that volatile, impalpable powder that flees under the hand. And the medium, because it offered me a better means of expression, remained with me. This lacklustre material, which has no inherent beauty, was a great help in my explorations of chiaroscuro and the invisible...It should be said, however, that charcoal leaves no room for lightness; it is full of gravity and one can only use it successfully in the same spirit. Nothing that does not stimulate the mind can produce worthwhile results in charcoal. It is on the verge of something unpleasant, something ugly.’

This drawing belongs with a small group of ‘noir’ charcoal drawings of figures seen imprisoned behind bars, datable to the early 1880’s. These include a drawing entitled The Convict of 1881 in the Museum of Modern Art in New York and a Face Behind Bars, formerly in the collection of Henri Petiet and today in a private collection.

Like many of Redon’s ‘noir’ charcoal drawings, the subject of the present sheet has remained profoundly enigmatic. A closely related drawing of an identical composition, of slightly larger dimensions, was in several Dutch collections in the first half of the 20th century and was most recently recorded with the art dealer Wolfgang Wittrock in Düsseldorf in 1994. Douglas Druick and Peter Zeger’s comments on that drawing are also relevant to the present sheet: ‘Religious life is likewise the theme of the contemporary drawing Redon exhibited at Le Gaulois under the title Behind the Grating...Haloed, the host-shaped head is depicted behind bars, fingers at its chin. In this respect, it recalls the figure in The Convict. But in place of the latter’s anguish, the face of the former appears serene, its closed eyes suggesting the ability to spiritually transcend its prison of the flesh by turning inward. This is possibly the unknown element to which the drawing’s alternate title, The Secret, alludes. It may also address the spatial ambiguities implied in this image of incarceration. For, on the one hand, the drawing implies that the host – the Church – is hostage, imprisoned and anguished like the convict...On the other, it is we, the viewers, who inhabit the dark prison of matter, who are cut off from a source of light and spirituality we can see but cannot reach.’

Either the present sheet or its variant was included - under the title Derrière la grille (Behind the Grating) - in Redon’s second one-man exhibition, held at the offices of the daily newspaper Le Gaulois in Paris in March 1882.

This drawing belongs with a small group of ‘noir’ charcoal drawings of figures seen imprisoned behind bars, datable to the early 1880’s. These include a drawing entitled The Convict of 1881 in the Museum of Modern Art in New York and a Face Behind Bars, formerly in the collection of Henri Petiet and today in a private collection.

Like many of Redon’s ‘noir’ charcoal drawings, the subject of the present sheet has remained profoundly enigmatic. A closely related drawing of an identical composition, of slightly larger dimensions, was in several Dutch collections in the first half of the 20th century and was most recently recorded with the art dealer Wolfgang Wittrock in Düsseldorf in 1994. Douglas Druick and Peter Zeger’s comments on that drawing are also relevant to the present sheet: ‘Religious life is likewise the theme of the contemporary drawing Redon exhibited at Le Gaulois under the title Behind the Grating...Haloed, the host-shaped head is depicted behind bars, fingers at its chin. In this respect, it recalls the figure in The Convict. But in place of the latter’s anguish, the face of the former appears serene, its closed eyes suggesting the ability to spiritually transcend its prison of the flesh by turning inward. This is possibly the unknown element to which the drawing’s alternate title, The Secret, alludes. It may also address the spatial ambiguities implied in this image of incarceration. For, on the one hand, the drawing implies that the host – the Church – is hostage, imprisoned and anguished like the convict...On the other, it is we, the viewers, who inhabit the dark prison of matter, who are cut off from a source of light and spirituality we can see but cannot reach.’

Either the present sheet or its variant was included - under the title Derrière la grille (Behind the Grating) - in Redon’s second one-man exhibition, held at the offices of the daily newspaper Le Gaulois in Paris in March 1882.

At a very young age, Odilon Redon was sent to live with an old uncle at Peyrelebade, a vineyard and estate surrounded by an abandoned park in a barren area of the Médoc region, northwest of Bordeaux. Here the young boy, who suffered from frail health and epilepsy, was to spend much of his childhood in relative solitude. Indeed, it was not until he was eleven that he was sent to school in Bordeaux, where at fifteen he began to take drawing classes. The most important influence on the young artist was Rodolphe Bresdin, whose studio in Bordeaux he frequented, and who was to prove decisive on his artistic development. It was from Bresdin, for example, that Redon learned the techniques of etching and lithography. Nevertheless, for most of his career Redon worked in something of an artistic vacuum, aware of the work of his contemporaries but generally preferring to follow his own path. His drawings and prints allowed him to express his lifelong penchant for imaginary subject matter, and were dominated by strange and unsettling images of fantastic creatures, disembodied heads and masks, solitary eyes, menacing spiders and other dreamlike forms. For much of the first thirty years of his career Redon worked almost exclusively in black, producing his ‘noirs’ in charcoal and chalk; the drawings he described as ‘mes ombres’, or ‘my shadows’.

It was not until 1881, when he was more than forty years old, that Redon first mounted a small exhibition of his work, to almost complete indifference on the part of critics or the public. The following year, however, a second exhibition of drawings and lithographs brought him to the attention of a number of critics. Redon’s reputation began to grow, and in 1884 he exhibited at the first Salon des Indépendants, which he had helped to organize. Two years later he was invited to show at the eighth and final Impressionist exhibition, and in the same year exhibited with Les XX, a group of avant-garde artists, writers and musicians in Brussels.

Towards the end of the 19th century Redon began to move away from working mainly in charcoal and black chalk in favour of a new emphasis on colour, chiefly using the medium of pastel but also watercolour, oil paint and distemper. Indeed, after about 1900 he seems to have almost completely abandoned working in black and white. Like his noirs, his pastels of floral still lives and portraits were popular with a few collectors, and several were included in exhibitions at Durand-Ruel in 1900, 1903 and 1906, and in subsequent exhibitions of his work in Paris and abroad. Despite this change in direction, however, Redon’s work remained unpopular with the public at large, and it was left to a few enlightened collectors to support the artist in his later years. Nevertheless, an entire room was devoted to Redon at the seminal Armory Show held in New York in 1913, an honour shared by Cezanne, Gauguin, Matisse and Van Gogh.

Provenance

Private collection, Paris, by 1991

Anonymous sale, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, 20 June 2007, lot 51

Private collection, until 2013.

Literature

Alec Wildenstein, Odilon Redon: Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint et dessiné. Vol.II, Mythes et légendes, Paris, 1994, pp.160-161, no.1067, illustrated p.160.