Odilon REDON

(Bordeaux 1840 - Paris 1916)

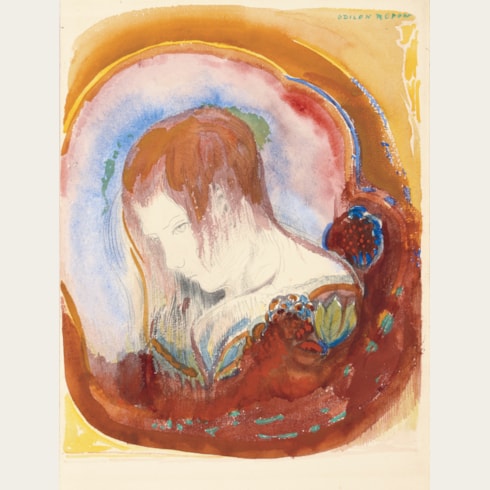

The Sleeping Child

Sold

Watercolour, gouache and pencil on card.

Dedicated and signed a / Simone / Fayet / - / 1 Janv. / 1916 / Od.R at the lower left.

Further signed ODILON REDON vertically at the lower left.

178 x 257 mm. (7 x 10 1/8 in.)

Dedicated and signed a / Simone / Fayet / - / 1 Janv. / 1916 / Od.R at the lower left.

Further signed ODILON REDON vertically at the lower left.

178 x 257 mm. (7 x 10 1/8 in.)

Although Odilon Redon had worked in watercolour as a youth at the beginning of the 1860’s, it was not until some thirty years later that he began again to work seriously in the medium. His watercolours, however, reflect a more reserved side of his experiments with colour, and his work in this fluid medium seems to have been done largely for his own pleasure. Redon’s use of the watercolour medium is largely confined to the later years of his career, as one scholar has noted, ‘when he turned from working primarily in black to enthusiastically embrace color. Indeed, the watercolors seem to have had a somewhat more private role in his oeuvre than his work in other media. Although he discussed his noirs, or fusains (charcoal drawings), his prints, pastels, and paintings in his correspondence – and in his posthumously published writings on art – watercolor is never discussed. The mature watercolors, however, treat themes that concerned the artist throughout his career, and some...are complete and accomplished works of art.’ Redon’s late watercolours were never exhibited in his lifetime and seem to have been retained by the artist until his death, shortly after which a number of examples were sold by his widow to private collectors. Redon’s watercolours were first seen by the public only in posthumous exhibitions of his work, such as that held at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune in 1917.

This extraordinary watercolour, which was given by Odilon Redon to Simone Fayet (1899-1961), the eldest daughter of his friend and patron Gustave Fayet, on New Year’s Day of 1916. A painter, collector and museum curator, Gustave Fayet (1865-1925) was a champion of several modern artists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in particular Gauguin and Redon. He owned over a hundred works by Gauguin and also collected many works by Redon, mainly from 1908 onwards. Fayet first met Redon in 1900, and in 1910 he commissioned two large murals from Redon to decorate the library of the Cistercian abbey of Fontfroide, near Narbonne, which Fayet had purchased and begun restoring in 1908.

The sleeping child in this drawing is depicted enclosed and protected by a sort of colourful aura or shell; a motif that is found in a number of Redon’s paintings, watercolours and pastels of the second decade of the 20th century. This tender and delicate composition, however, differs from Redon’s more sensual and, at times, disturbing images of Venus or Andromeda-like figures similarly enclosed in these organic shell-like forms, which are also sometimes reminiscent of underwater flowers.

Gustave Fayet’s daughter Simone would have been about fifteen years old at the time that Redon gave her this vibrant watercolour. The artist had, several years earlier, painted two pastel portraits of Simone as a young girl. In 1919 Simone Fayet married Paul Bacou, a government minister and diplomat; their daughter Roseline Bacou was to become one of the leading scholars of Redon’s oeuvre, and organized the first major modern retrospective of the artist’s work in Paris in 1956.

Given to Simone Fayet just six months before the artist’s death, and never before published or exhibited, this splendid watercolour remained in the possession of the Fayet and Bacou families until 2011.

This extraordinary watercolour, which was given by Odilon Redon to Simone Fayet (1899-1961), the eldest daughter of his friend and patron Gustave Fayet, on New Year’s Day of 1916. A painter, collector and museum curator, Gustave Fayet (1865-1925) was a champion of several modern artists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in particular Gauguin and Redon. He owned over a hundred works by Gauguin and also collected many works by Redon, mainly from 1908 onwards. Fayet first met Redon in 1900, and in 1910 he commissioned two large murals from Redon to decorate the library of the Cistercian abbey of Fontfroide, near Narbonne, which Fayet had purchased and begun restoring in 1908.

The sleeping child in this drawing is depicted enclosed and protected by a sort of colourful aura or shell; a motif that is found in a number of Redon’s paintings, watercolours and pastels of the second decade of the 20th century. This tender and delicate composition, however, differs from Redon’s more sensual and, at times, disturbing images of Venus or Andromeda-like figures similarly enclosed in these organic shell-like forms, which are also sometimes reminiscent of underwater flowers.

Gustave Fayet’s daughter Simone would have been about fifteen years old at the time that Redon gave her this vibrant watercolour. The artist had, several years earlier, painted two pastel portraits of Simone as a young girl. In 1919 Simone Fayet married Paul Bacou, a government minister and diplomat; their daughter Roseline Bacou was to become one of the leading scholars of Redon’s oeuvre, and organized the first major modern retrospective of the artist’s work in Paris in 1956.

Given to Simone Fayet just six months before the artist’s death, and never before published or exhibited, this splendid watercolour remained in the possession of the Fayet and Bacou families until 2011.

At a very young age, Odilon Redon was sent to live with an old uncle at Peyrelebade, a vineyard and estate surrounded by an abandoned park in a barren area of the Médoc region, northwest of Bordeaux. Here the young boy, who suffered from frail health and epilepsy, was to spend much of his childhood in relative solitude. Indeed, it was not until he was eleven that he was sent to school in Bordeaux, where at fifteen he began to take drawing classes. The most important influence on the young artist was Rodolphe Bresdin, whose studio in Bordeaux he frequented, and who was to prove decisive on his artistic development. It was from Bresdin, for example, that Redon learned the techniques of etching and lithography. Nevertheless, for most of his career Redon worked in something of an artistic vacuum, aware of the work of his contemporaries but generally preferring to follow his own path. His drawings and prints allowed him to express his lifelong penchant for imaginary subject matter, and were dominated by strange and unsettling images of fantastic creatures, disembodied heads and masks, solitary eyes, menacing spiders and other dreamlike forms. For much of the first thirty years of his career Redon worked almost exclusively in black, producing his ‘noirs’ in charcoal and chalk; the drawings he described as ‘mes ombres’, or ‘my shadows’.

It was not until 1881, when he was more than forty years old, that Redon first mounted a small exhibition of his work, to almost complete indifference on the part of critics or the public. The following year, however, a second exhibition of drawings and lithographs brought him to the attention of a number of critics. Redon’s reputation began to grow, and in 1884 he exhibited at the first Salon des Indépendants, which he had helped to organize. Two years later he was invited to show at the eighth and final Impressionist exhibition, and in the same year exhibited with Les XX, a group of avant-garde artists, writers and musicians in Brussels.

Towards the end of the 19th century Redon began to move away from working mainly in charcoal and black chalk in favour of a new emphasis on colour, chiefly using the medium of pastel but also watercolour, oil paint and distemper. Indeed, after about 1900 he seems to have almost completely abandoned working in black and white. Like his noirs, his pastels of floral still lives and portraits were popular with a few collectors, and several were included in exhibitions at Durand-Ruel in 1900, 1903 and 1906, and in subsequent exhibitions of his work in Paris and abroad. Despite this change in direction, however, Redon’s work remained unpopular with the public at large, and it was left to a few enlightened collectors to support the artist in his later years. Nevertheless, an entire room was devoted to Redon at the seminal Armory Show held in New York in 1913, an honour shared by Cezanne, Gauguin, Matisse and Van Gogh.

Provenance

Presented by the artist to Simone Fayet, Béziers, on 1 January 1916

Thence by descent until 2011.