Francesco GUARDI

(Venice 1712 - Venice 1793)

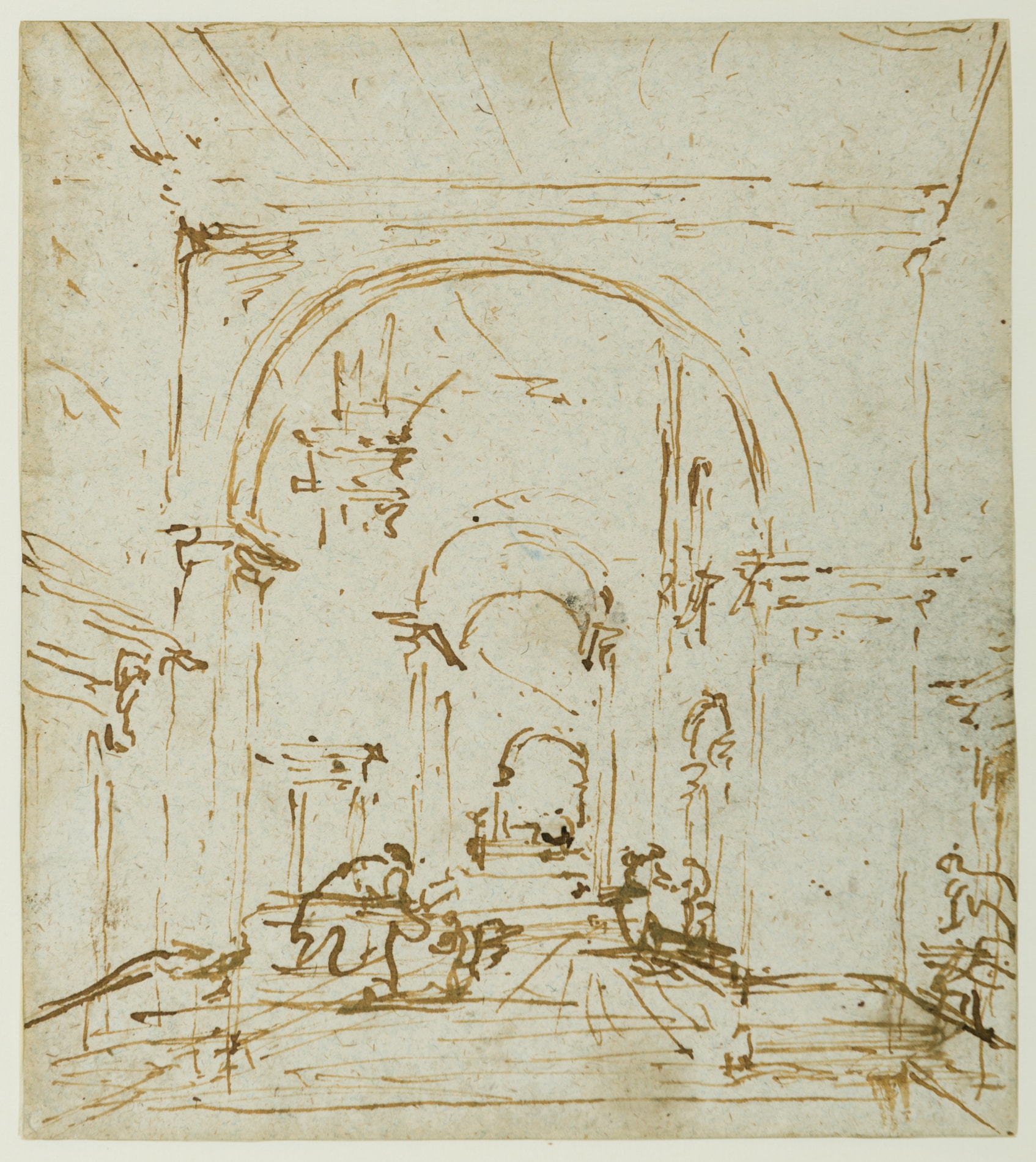

Perspective Study of a Venetian Colonnade

A sketch of the ceiling of a colonnade in black chalk and brown ink on the verso.

171 x 152 mm. (6 3/4 x 6 in.)

Guardi’s capriccio studies are perhaps the artist’s most individual works as a draughtsman. In his survey of Guardi’s drawings, published in 1951, James Byam Shaw noted that drawings of architectural capricci, such as the present sheet, were ‘evidently more to the taste of Venetian collectors than of foreign visitors at the time. The Venetian gentleman needed no souvenir: he could admire the gay scene in the Piazza any day of his life, or watch the Regatta, if he chose, from his balcony on the Grand Canal. But a Capriccio was something à la mode, a work of the imagination, a work of art. It is the Veduta ideata (imaginary view), as opposed to the Veduta presa dal Luogo(view taken on the spot)….but this particular category, which is so characteristic of Guardi, consists in the combination of motives taken from Venetian or other architecture, some of which are introduced with variations again and again…the Architectural Capriccio, whether in drawing or painting - and many of the drawings of this kind were adapted eventually on canvas or panel – is clearly distinct from the Venetian View in intention. It is a composition and not a view…even where a motive derives from the realities of the Venetian scene, the spirit is elsewhere, in the region of fancy.’

Drawn with a summary technique in pen alone, without wash, the present sheet may be compared with a handful of equally freely-drawn perspectival studies by Guardi of his late period, in particular a drawing of The Rialto Bridge with the Palazzo Manin in the collection of the Museo Correr in Venice, as well as two pen sketches of the Portico of the Torre dell’Orologio Looking Towards the Piazzetta and The Cortile of the Palazzo Soranzo van Axel, both also in the Museo Correr. Also comparable is an architectural sketch of the part of Rialto bridge on the verso of a drawing in the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York and a Vestibule and Staircase of a Palace in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

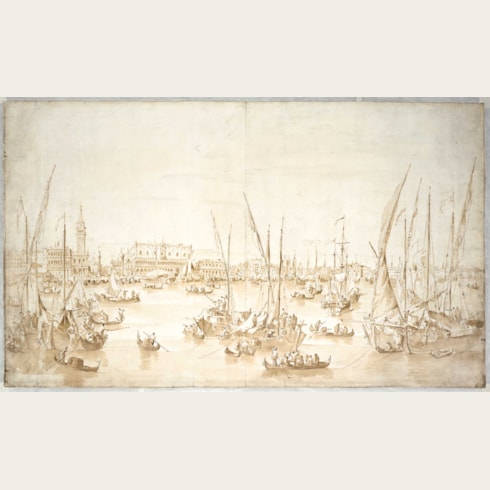

By 1761 Guardi had joined the painter’s guild in Venice, and soon established a reputation as a painter of Venetian views and imaginary landscapes, or capricci. He enjoyed a market for his views of Venice, painted with loose, spirited brushwork and transparent washes which allowed the artist the freedom to explore atmospheric effects. While he was fairly successful as a view painter, Guardi never achieved the level of fame enjoyed by Canaletto, particularly among foreign visitors to Venice. Nevertheless, his work was popular with British tourists to the city, and among his patrons was the English diplomat John Strange, the British resident in Venice between 1773 and 1790, who commissioned a series of view paintings of country villas on the terraferma. It was not until 1784, at the age of seventy-one, that Guardi was admitted to the Accademia in Venice, as a ‘pittore prospetico’. His son Giacomo was also an artist, and continued the family studio well into the 19th century.

As Rudolf Wittkower has written, ‘Francesco Guardi’s art has often been compared with the music of Mozart. Despite his modernity, Guardi was a man of his century and, more specifically, a man of the Rococo. He continued creating his spirited capriccios and limpid visions of Venice long after the spectre of a new heroic age had broken in on Europe. When he died in the fourth year of the French Revolution, few may have known or cared that the reactionary backwater of Venice…had harboured a great revolutionary of the brush.’

A gifted draughtsman, Guardi was a prolific and spirited master of the pen. (Antonio Morassi listed over 650 drawings by the artist in his catalogue raisonné of 1984.) As has been noted, ‘There was something of Watteau in his make-up; he was seldom without a sketchbook at hand in which to jot down anything that took his fancy whether or not it was used in a painting later on.’ Guardi’s drawings include sheets of studies of figures and boats, architectural scenes, designs for wall and ceiling decorations, landscape capricci and topographical Venetian views. ‘By 1765 or so’, as another scholar has written, ‘Guardi had developed his personal style, in which a nervous, flickering line and subtly and richly varied washes give an atmospheric brilliance and luminosity that transform the subject into pictorial enchantment.’

A large and varied collection of drawings by the artist is today in the Museo Correr in Venice, acquired by Count Teodoro Correr from Giacomo Guardi. These are, however, mostly sketches and quick studies for pictures, rather than large-scale, finished sheets, and as such represent the typical contents of an artist’s workshop. Smaller but significant collections of drawings by Guardi are today in the British Museum and the Courtauld Gallery in London, the Pierpont Morgan Library and Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and the Louvre in Paris.

Provenance

Thence by descent in the Verdé-Delisle family to a private collection, Belgium

Anonymous sale, Neuilly-sur-Seine, Hôtel de Ventes [Aguttes], 27 March 2012, lot 18 (as Attributed to Francesco Guardi)

Jean-Luc Baroni Ltd., London, in 2014

Private collection, New York.