Francesco GUARDI

(Venice 1712 - Venice 1793)

The Lion of Saint Mark

Inscribed PAX / TIB / MArCE / EVA /GELIST / A / MEUS on the book. Further inscribed Dominiquain on the former mount.

203 x 300 mm. (8 x 11 3/4 in.)

The present sheet is likely to be an early drawing by Francesco Guardi. As Hylton Thomas has noted of Guardi, ‘Like other important Venetian or partly Venetian draughtsmen of his time (and Tiepolo and Piranesi spring to mind), Guardi was as versatile in the techniques he employed as he was in creating new subjects or transforming already existing ones. Ink, wash, chalks, alone and in varying combinations, were used with pen and brush.’ The use of watercolour is found in relatively few drawings by the artist, such as two designs for ceiling decorations, one in the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris and the other in the former City Museum and Art Gallery (now The Box) in Plymouth, and two large drawings of elaborate ceremonial bissone, or festival gondolas for a Venetian regatta, in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

This drawing remains unrelated to any known painting by Guardi. It may, however, have been inspired by a similar lion in a decorative painting of Cybele by his brother Antonio Guardi, in a Venetian private collection. Animal studies by Francesco Guardi are rare, and include two somewhat comparable drawings of seated lions in the Courtauld Gallery in London and a study of two dogs in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

Antonio Morassi has noted that the few drawings of animals by Guardi that are known may have been inspired by similar studies produced by the artist’s nephew, Domenico Tiepolo. Indeed, an alternative attribution to the younger artist for the present sheet has been suggested by both Ugo Ruggeri and George Knox, although Bernard Aikema rejected this proposal and preferred to maintain the attribution to Francesco Guardi. While the free underdrawing in black chalk is certainly akin to that found in many of Domenico Tiepolo’s drawings, especially of animals, the nervous penwork in the present sheet is much closer to Guardi’s manner. Furthermore, the combination of brown ink and coloured washes is not found in Domenico Tiepolo’s drawings. On balance, therefore, we have preferred to maintain an attribution to Francesco Guardi for this fine sheet.

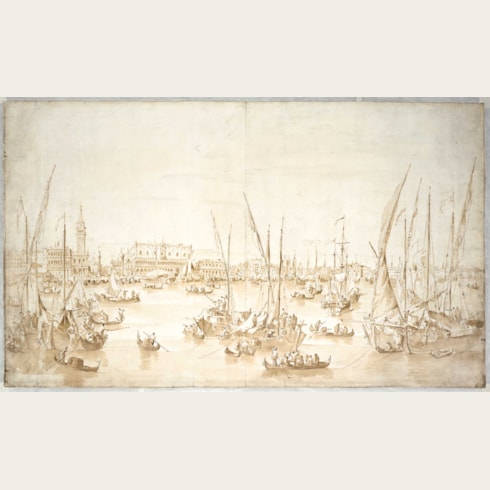

By 1761 Guardi had joined the painter’s guild in Venice, and soon established a reputation as a painter of Venetian views and imaginary landscapes, or capricci. He enjoyed a market for his views of Venice, painted with loose, spirited brushwork and transparent washes which allowed the artist the freedom to explore atmospheric effects. While he was fairly successful as a view painter, Guardi never achieved the level of fame enjoyed by Canaletto, particularly among foreign visitors to Venice. Nevertheless, his work was popular with British tourists to the city, and among his patrons was the English diplomat John Strange, the British resident in Venice between 1773 and 1790, who commissioned a series of view paintings of country villas on the terraferma. It was not until 1784, at the age of seventy-one, that Guardi was admitted to the Accademia in Venice, as a ‘pittore prospetico’. His son Giacomo was also an artist, and continued the family studio well into the 19th century.

As Rudolf Wittkower has written, ‘Francesco Guardi’s art has often been compared with the music of Mozart. Despite his modernity, Guardi was a man of his century and, more specifically, a man of the Rococo. He continued creating his spirited capriccios and limpid visions of Venice long after the spectre of a new heroic age had broken in on Europe. When he died in the fourth year of the French Revolution, few may have known or cared that the reactionary backwater of Venice…had harboured a great revolutionary of the brush.’

A gifted draughtsman, Guardi was a prolific and spirited master of the pen. (Antonio Morassi listed over 650 drawings by the artist in his catalogue raisonné of 1984.) As has been noted, ‘There was something of Watteau in his make-up; he was seldom without a sketchbook at hand in which to jot down anything that took his fancy whether or not it was used in a painting later on.’ Guardi’s drawings include sheets of studies of figures and boats, architectural scenes, designs for wall and ceiling decorations, landscape capricci and topographical Venetian views. ‘By 1765 or so’, as another scholar has written, ‘Guardi had developed his personal style, in which a nervous, flickering line and subtly and richly varied washes give an atmospheric brilliance and luminosity that transform the subject into pictorial enchantment.’

A large and varied collection of drawings by the artist is today in the Museo Correr in Venice, acquired by Count Teodoro Correr from Giacomo Guardi. These are, however, mostly sketches and quick studies for pictures, rather than large-scale, finished sheets, and as such represent the typical contents of an artist’s workshop. Smaller but significant collections of drawings by Guardi are today in the British Museum and the Courtauld Gallery in London, the Pierpont Morgan Library and Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and the Louvre in Paris.

Provenance

P. & D. Colnaghi, London, in 1997

Private collection.

Literature

Exhibition