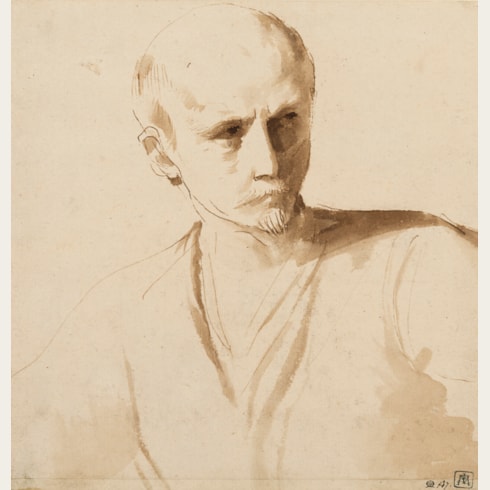

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri GUERCINO

(Cento 1591 - Bologna 1666)

A Soldier in Armour Facing Right, Holding a Shield and Looking to the Left

Some small made-up areas along the bottom edge and at the lower right corner.

270 x 197 mm. (10 5/8 x 7 3/4 in.)

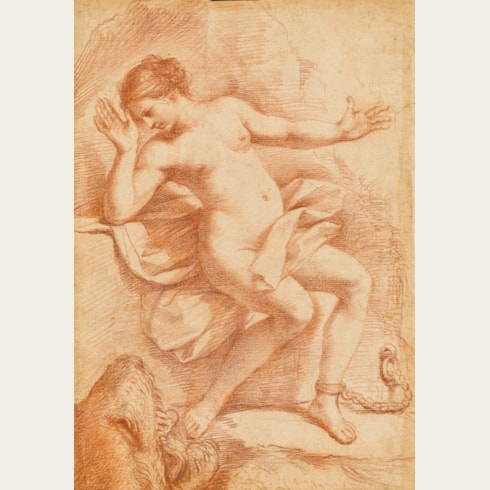

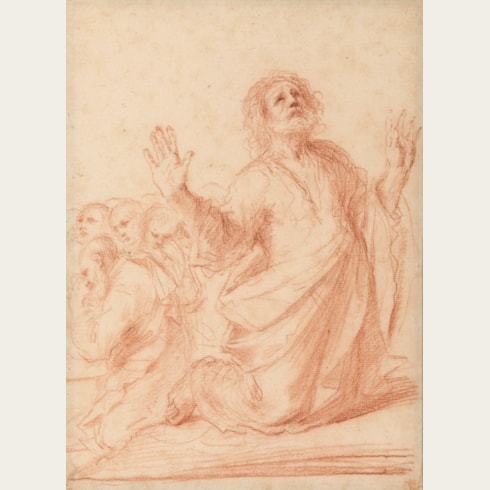

This splendid drawing – recently described by David Stone as ‘a delicate sketch in black chalk of a soldier, looking left but moving towards the right…a stunning drawing from Guercino’s mature period, fully consonant with drawings and paintings of the 1640s’ – has been related by Stone to Guercino’s large canvas of Hersilia Intervening Between Romulus and Tatius (or The Sabine Women Intervening to Bring Peace Between the Romans and the Sabines), painted in 1645 for the Parisian collector Louis Phélypeaux de La Vrillière and now in the Louvre. The drawing would appear to represent an early and unused idea for the pose of the striding warrior – usually identified as Titus Tatius, King of the Sabines - at the left of the composition, although in the final painting this figure is shown with a short beard. While the youthful appearance of the figure in the present sheet would seem to argue against it being a study for the bearded and apparently slightly older warrior in the painting, it would not be unusual for Guercino to experiment with different ideas for the facial appearance of this figure. Indeed, another preparatory drawing that can be definitively related to the Louvre canvas - a pen and ink sheet in a private American collection - depicts several profile studies of the head of the same warrior, some of which show him unbearded.

The warrior in this drawing, wearing armour and a helmet akin to that of the equivalent figure in the Louvre painting, and holding a similar oval shield, looks behind him, and seems to be in the act of placing his shield on the ground. It is conceivable, therefore, that when planning the composition Guercino had initially considered having the Sabine princess Hersilia approach Tatius from the left to beseech him to lay down his arms, and to show him beginning to lower his shield. In the end, however, Guercino chose to depict the more dramatic episode of the combat between the Sabine king Tatius and his Roman challenger Romulus about to commence, before the truce brought about by Hersilia’s mediation.

The present sheet can be likened to another drawing in black chalk that has also been related to the painting of Hersilia Intervening Between Romulus and Tatius of 1645; a head of a helmeted warrior, similarly youthful and unbearded, in the collection of the Teyler Museum in Haarlem. A pen and ink drawing of a soldier in a similar helmet, in the Princeton University Art Museum, has also been tentatively related to the Louvre picture. Among a handful of other drawings that served as preparatory studies for the Hersilia Intervening Between Romulus and Tatius is a stylistically comparable study in black chalk for the figure of Hersilia, today in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle.

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, known as Il Guercino (‘the squinter’) because he was cross-eyed, was by the second decade of the 17th century one of the leading painters in the province of Emilia. Born in Cento, a small town between Bologna and Ferrara, Guercino was largely self-taught, although his early work was strongly influenced by the paintings of Ludovico Carracci. In 1617 he was summoned to Bologna by Alessandro Ludovisi, the Cardinal Archbishop of Bologna, and there painted a number of important altarpieces, typified by the Saint William Receiving the Monastic Habit, painted in 1620 and now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna. When Ludovisi was elected Pope Gregory XV in 1621, Guercino was summoned to Rome to work for the pontiff and his nephew, Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi. It was in Rome that Guercino painted some of his most celebrated works, notably the ceiling fresco of Aurora in the Casino Ludovisi and the large altarpiece of The Burial and Reception into Heaven of Saint Petronilla for an altar in Saint Peter’s. The papacy of Gregory XV was short-lived, however, and on the death of the Pope in 1623 Guercino returned to his native Cento. He remained working in Cento for twenty years, though he continued to receive commissions from patrons throughout Italy and beyond, and turned down offers of employment at the royal courts in London and Paris. Following the death of Guido Reni in 1642, Guercino moved his studio to Bologna, where he received commissions for religious pictures of the sort that Reni had specialized in, and soon inherited his position as the leading painter in the city.

Guercino was among the most prolific draughtsmen of the 17th century in Italy, and his preferred medium was pen and brown ink, although he also worked in red chalk, black chalk, and charcoal. He appears to have assiduously kept his drawings throughout his long career, and to have only parted with a few of them. Indeed, more drawings by him survive today than by any other Italian artist of the period. On his death in 1666 all of the numerous surviving sheets in his studio passed to his nephews and heirs, the painters Benedetto and Cesare Gennari, known as the ‘Casa Gennari’.

The drawings of Guercino, which include figural and compositional studies, landscapes, caricatures and genre scenes, have always been coveted by later collectors and connoisseurs. Indeed, the 18th century amateur Pierre-Jean Mariette noted of the artist that ‘Ce peintre a outre cela une plume tout-à-faite séduisante’. The largest extant group of drawings by Guercino is today in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle; these were acquired from the Gennari family by King George III’s librarian, Richard Dalton, between about 1758 and 1764.

Provenance

Anonymous sale, Rome, Bertolami Fine Art, 9 May 2019, lot 4

Maurizio Nobile Fine Art, Bologna, Milan and Paris.

Literature