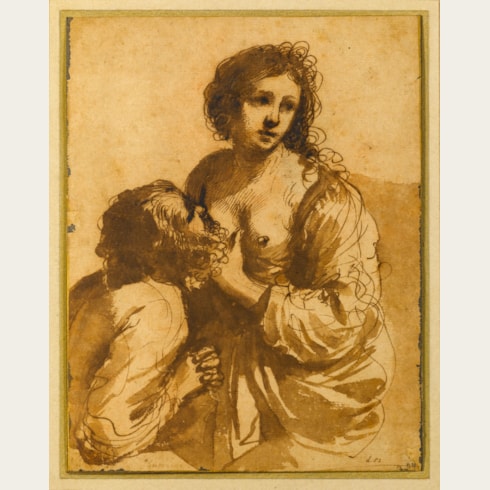

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri GUERCINO

(Cento 1591 - Bologna 1666)

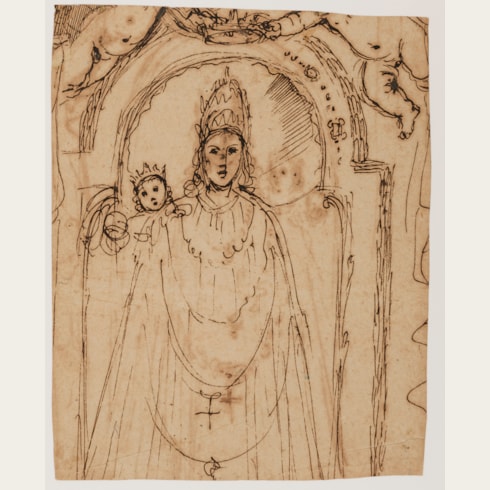

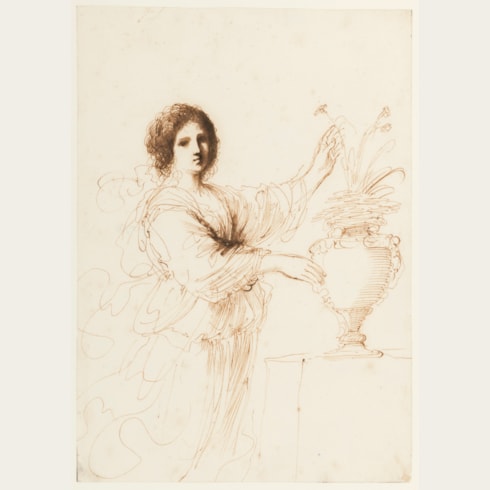

A Sibyl

Two small made up areas at the lower left corner and the left centre, near the figure’s proper right shoulder.

Laid down on an 18th or 19th century mount.

185 x 211 mm. (7 1/4 x 8 3/8 in.)

Nicholas Turner has suggested that the present sheet may be related to a half-length painting of theSibyl Hellespontica, today in the collection of the National Trust at Ickworth House in Suffolk. (Sometimes also known as the Trojan Sibyl, the Hellespontine Sibyl was the priestess of the Oracle of Apollo at Dardania and is said to have predicted the crucifixion of Christ.) The painting is recorded as a work by Guercino when in the collection of Frederick Hervey, 1st Marquess of Bristol (1769-1859), and is noted as hanging in the library at Ickworth House in the 1830s. The composition is not known in any other version, and is not listed in Guercino’s Libro dei Conti. Until recently the painting was thought to be later in date and was attributed to Guercino’s nephew and pupil Benedetto Gennari the Younger. However, the high quality of the Ickworth canvas has led to a recent reassessment of it as, at least in part, an autograph work by the master, although its dating has remained something of a question mark.

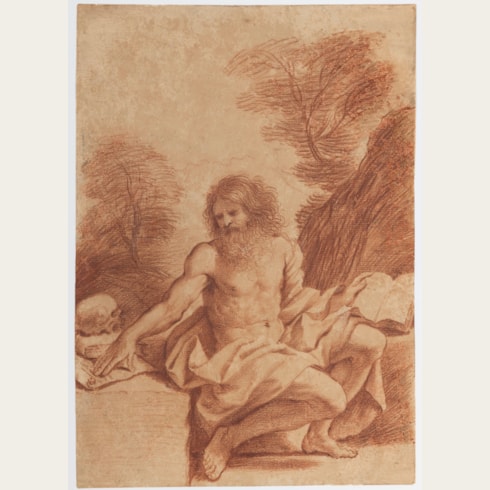

Turner has compared the present sheet with two red chalk studies for the seated sibyls painted by Guercino in the Duomo in Piacenza in 1627, one in the Nasjonalgaleriet in Oslo and the other in the Szépmüvészeti Múzeum in Budapest. David Stone has, however, noted that the present sheet is more likely to be a later work of the first half of the 1630s. A comparison, on stylistic grounds, may be made with such red chalk drawings by Guercino as A Peasant Woman with a Basket of Grapes in the Uffizi in Florence, as well as two sheets at Windsor Castle; A Woman Showing a Nude Baby to Two Attendants and Saint Geneviève of Paris. Likewise similar in technique and handling is a drawing of The Virgin and Child in red chalk which appeared on the art market in 1998 and 2001.

A coarsely reworked counterproof of this drawing is in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, part of an extensive collection of nearly 240 offsets of red chalk drawings by Guercino acquired from the Casa Gennari in Bologna, in the late 1750s or early 1760s, by Richard Dalton for King George III. Although the dimensions of the Windsor counterproof are slightly larger than the present sheet, the scale is identical, and it would appear that this drawing has been trimmed slightly at the left and right edges. Another retouched counterproof at Windsor, of slightly larger dimensions, shows the same woman in an identical pose, but without the scroll and with much more sketchy outlines, and may record a lost initial sketch by Guercino for the present composition.

The album of counterproofs of Guercino drawings acquired by Dalton from the Gennari heirs in the 18th century contained offsets of original drawings by the master that were part of the contents of the artist’s studio in Bologna. While some of these counterproofs were pulled during Guercino’s lifetime, it would seem that most of them were done some time after his death, in order to preserve records of the original drawings before they were sold from the Casa Gennari. As Denis Mahon and Nicholas Turner have noted, ‘It is possible that the Windsor offsets were sold by Guercino’s heirs instead of the original red chalk drawings that they were either unwilling to sell to Richard Dalton or that he was unwilling to buy; he was apparently satisfied with the purchase of some of these ‘reproductions’ as supplements to the large group of autograph drawings he had already secured.’ It is likely, therefore, that the provenance of the present sheet can be traced back to the Casa Gennari.

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, known as Il Guercino (‘the squinter’) because he was cross-eyed, was by the second decade of the 17th century one of the leading painters in the province of Emilia. Born in Cento, a small town between Bologna and Ferrara, Guercino was largely self-taught, although his early work was strongly influenced by the paintings of Ludovico Carracci. In 1617 he was summoned to Bologna by Alessandro Ludovisi, the Cardinal Archbishop of Bologna, and there painted a number of important altarpieces, typified by the Saint William Receiving the Monastic Habit, painted in 1620 and now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna. When Ludovisi was elected Pope Gregory XV in 1621, Guercino was summoned to Rome to work for the pontiff and his nephew, Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi. It was in Rome that Guercino painted some of his most celebrated works, notably the ceiling fresco of Aurora in the Casino Ludovisi and the large altarpiece of The Burial and Reception into Heaven of Saint Petronilla for an altar in Saint Peter’s. The papacy of Gregory XV was short-lived, however, and on the death of the Pope in 1623 Guercino returned to his native Cento. He remained working in Cento for twenty years, though he continued to receive commissions from patrons throughout Italy and beyond, and turned down offers of employment at the royal courts in London and Paris. Following the death of Guido Reni in 1642, Guercino moved his studio to Bologna, where he received commissions for religious pictures of the sort that Reni had specialized in, and soon inherited his position as the leading painter in the city.

Guercino was among the most prolific draughtsmen of the 17th century in Italy, and his preferred medium was pen and brown ink, although he also worked in red chalk, black chalk, and charcoal. He appears to have assiduously kept his drawings throughout his long career, and to have only parted with a few of them. Indeed, more drawings by him survive today than by any other Italian artist of the period. On his death in 1666 all of the numerous surviving sheets in his studio passed to his nephews and heirs, the painters Benedetto and Cesare Gennari, known as the ‘Casa Gennari’.

The drawings of Guercino, which include figural and compositional studies, landscapes, caricatures and genre scenes, have always been coveted by later collectors and connoisseurs. Indeed, the 18th century amateur Pierre-Jean Mariette noted of the artist that ‘Ce peintre a outre cela une plume tout-à-faite séduisante’. The largest extant group of drawings by Guercino is today in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle; these were acquired from the Gennari family by King George III’s librarian, Richard Dalton, between about 1758 and 1764.

Provenance

Thence by descent to Carlo Gennari, Bologna, and probably sold in the second half of the 18th century

Anonymous sale, London, Rosebery’s, 4 June 2020, lot 109 (as Workshop of Guercino)

Private collection.