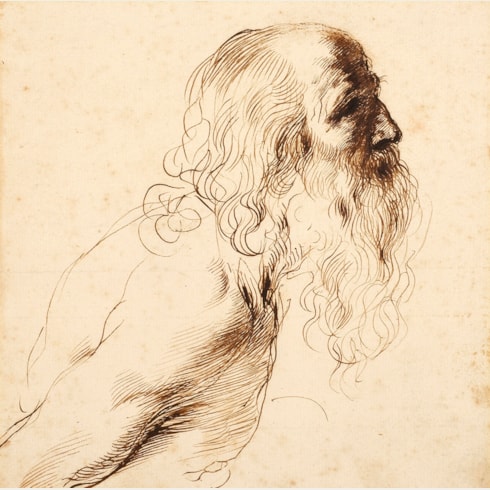

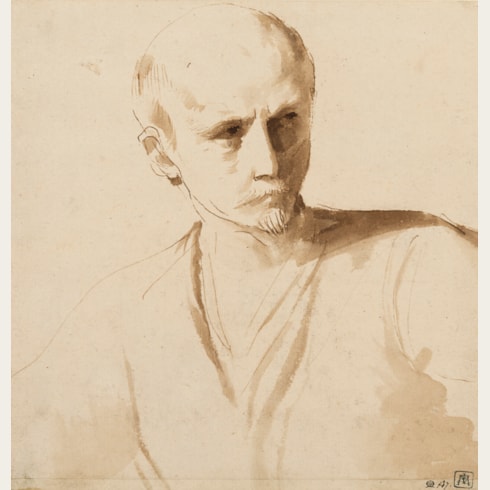

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri GUERCINO

(Cento 1591 - Bologna 1666)

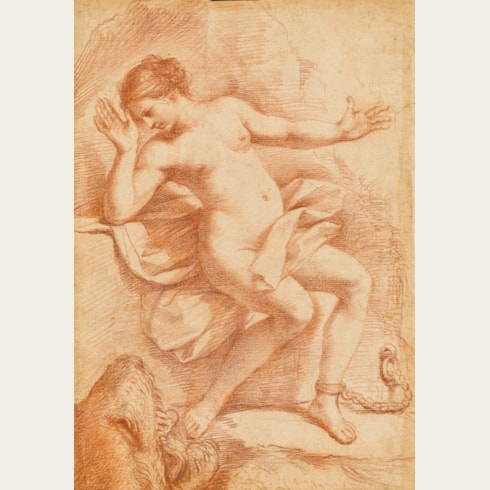

Roman Charity: Cimon and Pero

Illegibly inscribed [da Cento?] in brown ink on the verso, partly cut off at the top edge of the sheet.

251 x 236 mm. (9 7/8 x 9 1/4 in.)

The exemplary story of Cimon and Pero is taken from the Roman historian Valerius Maximus’s Factorum ac dictorum memorabilium libri IX (Nine Books of Memorable Deeds and Sayings), a compendium of stories of Ancient Rome, written around 30 BC. The aged Cimon is imprisoned and left to die of starvation, but is secretly nursed by his daughter Pero, who keeps him alive by doing so. This act of filial piety and selflessness impresses the old man’s jailers, and he is set free.

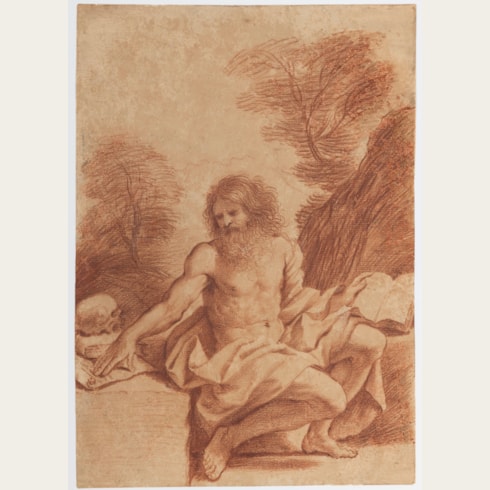

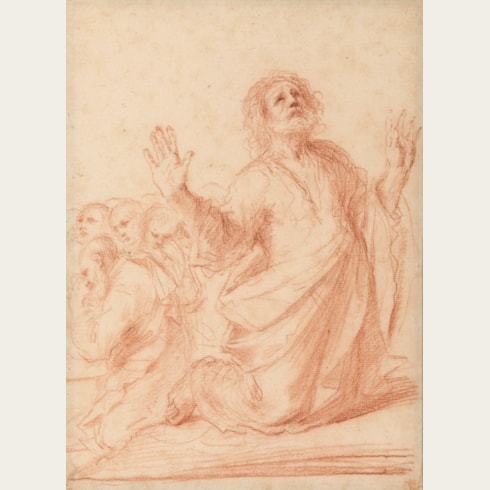

At least four other drawings of this subject by Guercino are known, all of which may be related to the 1639 Bentivoglio commission. A pen and ink drawing of Cimon and Pero, from the Casa Gennari, Bouverie, Earls of Gainsborough and Oppé collections, appeared at auction in 1971 and 2006 and is now in a private collection in Germany, while another pen drawing of the same subject was on the art market in 1994. A third pen and ink drawing, formerly in the collections of Padre Sebastiano Resta, Lord Somers and Richard Houlditch, was with Stephen Ongpin Fine Art in 2014 and reappeared on the art market in Paris in 2019. In all three of these drawings the arrangement of the figures is identical to that seen in the present sheet. A drawing of Roman Charity in red chalk, with the figures transposed so that Cimon is at the right and Pero at the left, was at one time in the H. S. Reitlinger collection and was sold at auction in 1953. What appears to be a copy of the present sheet was on the art market in New York in 2012 and is now in a private collection.

As David Stone has noted of this recent addition to the corpus of Guercino’s drawings, ‘Of the many preparatory sheets [for the 1639 painting] thus far identified, the present sheet is closest to the scheme realized...As in the latter, Cimon’s shackle and chains on the stone block feature prominently in the newly identified drawing, which has wonderfully realized shadows for the individual links of the chains. Guercino’s treatment of Cimon’s right hand is particularly sensitive, giving the viewer a sense of the man’s age and fragility. The daughter’s left hand, meanwhile, simultaneously conceals and reveals: with her fingers, with a degree of modesty, she holds her right breast to give suck to her prisoner-father; with her thumb she presses up against the contours of her left breast, reinforcing the voluptuousness of her body.’ An interesting pentiment is noticeable in the present sheet, where Guercino first drew Pero’s head angled more to the left and looking down at Cimon, before deciding to tilt her head to the right to look away from her father as he nurses at her breast.

Stone has further pointed out of the present sheet that ‘Guercino’s drawing has a strong vertical red-chalk line running prominently down the left side of the sheet, leaving a considerable margin. Perhaps early on, as he confronted a blank or nearly blank sheet, he wanted to set the proportions of his painting (typical of Guercino, he may not have yet fully settled on making a horizontal composition; he was constantly experimenting). But he seems to have regretted this line, and drew right over it (and also, in a sense, lessened its impact with hatching in the upper left.)’ A reworked offset or counterproof of this drawing is in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle. Since the album of counterproofs of Guercino drawings acquired from the Gennari heirs for the Royal Collection, sometime between 1758 and 1763, contained offsets of original drawings by the master that were part of the contents of the artist’s studio, it is almost certain that the present sheet was once part of the very large corpus of drawings by Guercino in the Casa Gennari.

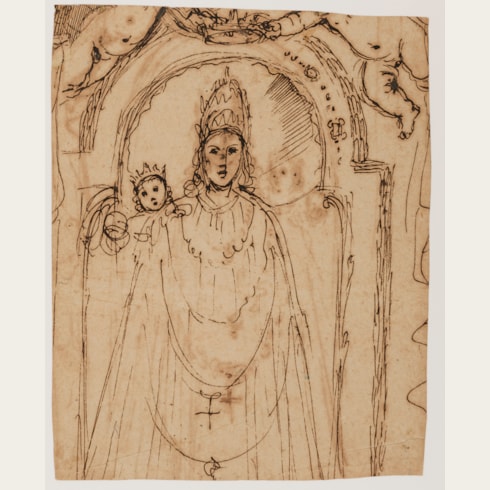

Guercino also treated the closely related subject of The Roman Daughter, in which a woman suckles her imprisoned mother, in two pen and ink drawings; one in the Royal Collection at Windsor and the other sold at auction in 1999 and now in a private collection in Switzerland.

An early 19th century etching after a lost Guercino drawing of the subject of Roman Charity, published in 1808 by the painter and printmaker Antonio Bresciani (1720-1817), shares some compositional similarities with the present sheet.

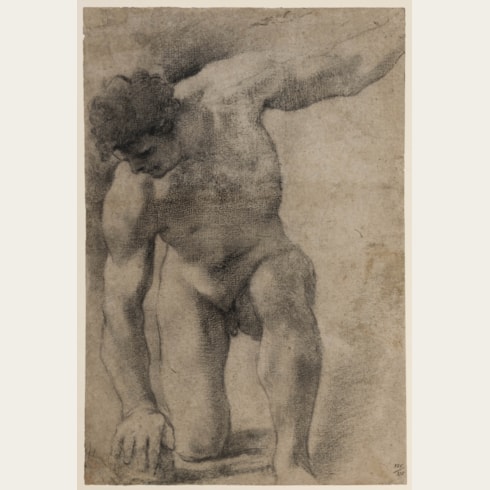

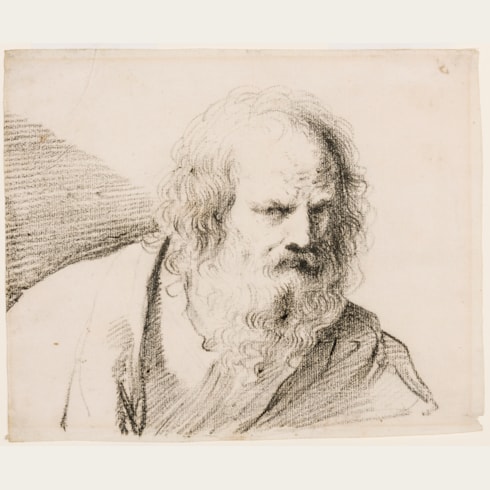

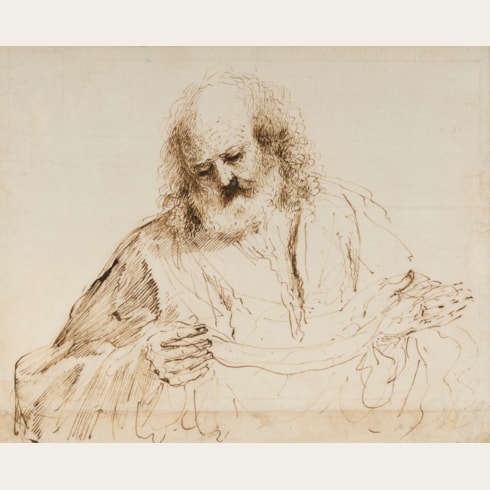

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, known as Il Guercino (‘the squinter’) because he was cross-eyed, was by the second decade of the 17th century one of the leading painters in the province of Emilia. Born in Cento, a small town between Bologna and Ferrara, Guercino was largely self-taught, although his early work was strongly influenced by the paintings of Ludovico Carracci. In 1617 he was summoned to Bologna by Alessandro Ludovisi, the Cardinal Archbishop of Bologna, and there painted a number of important altarpieces, typified by the Saint William Receiving the Monastic Habit, painted in 1620 and now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna. When Ludovisi was elected Pope Gregory XV in 1621, Guercino was summoned to Rome to work for the pontiff and his nephew, Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi. It was in Rome that Guercino painted some of his most celebrated works, notably the ceiling fresco of Aurora in the Casino Ludovisi and the large altarpiece of The Burial and Reception into Heaven of Saint Petronilla for an altar in Saint Peter’s. The papacy of Gregory XV was short-lived, however, and on the death of the Pope in 1623 Guercino returned to his native Cento. He remained working in Cento for twenty years, though he continued to receive commissions from patrons throughout Italy and beyond, and turned down offers of employment at the royal courts in London and Paris. Following the death of Guido Reni in 1642, Guercino moved his studio to Bologna, where he received commissions for religious pictures of the sort that Reni had specialized in, and soon inherited his position as the leading painter in the city.

Guercino was among the most prolific draughtsmen of the 17th century in Italy, and his preferred medium was pen and brown ink, although he also worked in red chalk, black chalk, and charcoal. He appears to have assiduously kept his drawings throughout his long career, and to have only parted with a few of them. Indeed, more drawings by him survive today than by any other Italian artist of the period. On his death in 1666 all of the numerous surviving sheets in his studio passed to his nephews and heirs, the painters Benedetto and Cesare Gennari, known as the ‘Casa Gennari’.

The drawings of Guercino, which include figural and compositional studies, landscapes, caricatures and genre scenes, have always been coveted by later collectors and connoisseurs. Indeed, the 18th century amateur Pierre-Jean Mariette noted of the artist that ‘Ce peintre a outre cela une plume tout-à-faite séduisante’. The largest extant group of drawings by Guercino is today in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle; these were acquired from the Gennari family by King George III’s librarian, Richard Dalton, between about 1758 and 1764.

Provenance

Thence by descent to Carlo Gennari, Bologna and probably sold in the second half of the 18th century

Private collection; Fondantico, Bologna.