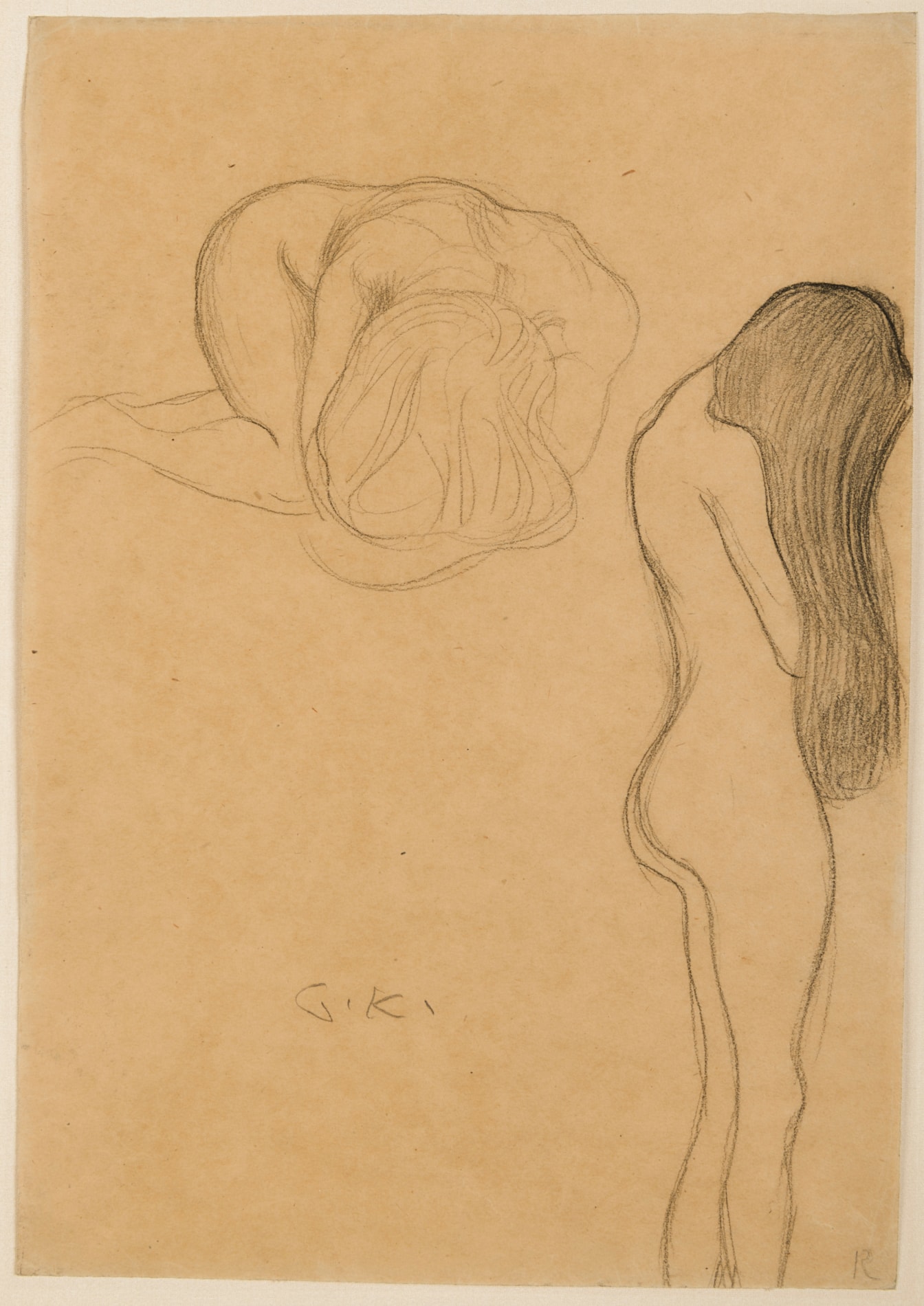

Gustav KLIMT

(Vienna 1862 - Vienna 1918)

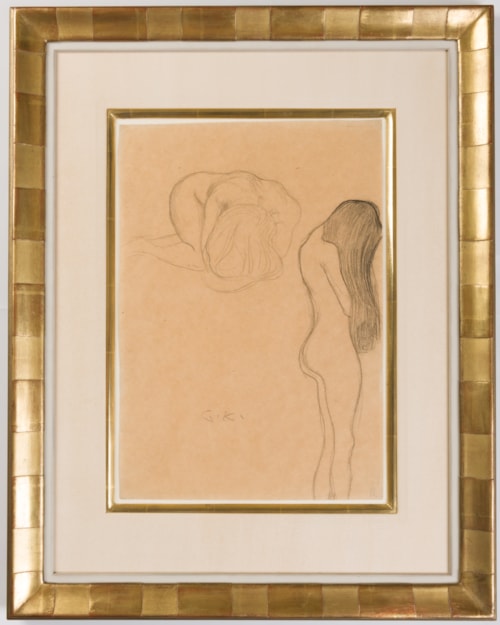

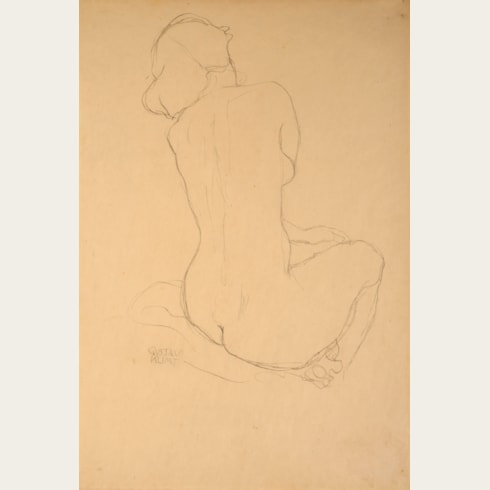

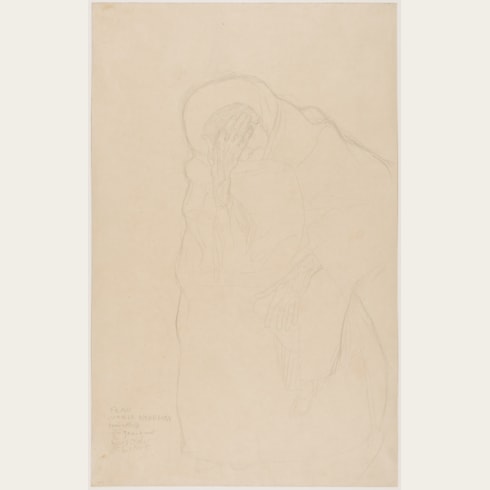

Two Female Nudes

Sold

Black chalk on buff paper.

Signed with the artist’s initials G. K. at the lower centre and inscribed R at the lower right.

Numbered 21 in a circle on the verso.

443 x 309 mm. (17 3/8 x 12 1/8 in.)

Signed with the artist’s initials G. K. at the lower centre and inscribed R at the lower right.

Numbered 21 in a circle on the verso.

443 x 309 mm. (17 3/8 x 12 1/8 in.)

The present sheet is part of a group of figure drawings that can be related to one of Gustav Klimt’s most significant public works; the monumental Beethoven Frieze (Beethovenfries) fresco of 1901-1902, designed for the Secession Building in Vienna, on the occasion of the 14th Secession exhibition of 1902. The Secession exhibition that year was unusual in that it was devoted to the presentation of a single work; a large sculpture of Beethoven by the German artist Max Klinger. Flanking the gallery that housed this sculpture were two side rooms, and it was the frieze decoration of one of these that was entrusted to Klimt. Originally intended as an ephemeral, temporary decorative scheme, to be destroyed after the Secession exhibition, Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze was instead acquired by the Austrian industrialist Carl Reininghaus, and by 1915 had passed to the Viennese collector August Lederer. The entire ensemble, divided into eight panels, is today in the collection of the Österreichische Galerie in Vienna and on permanent display in the Secession Building.

As Tobias Natter has noted of the origins of the Beethoven Frieze project, ‘The development of the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk – or total work of art – and its realization in a number of exhibitions and architectural schemes can possibly be considered the most significant achievement of the artistic revolution in Vienna around 1900. Artists, architects and designers as well as poets, dramatists and musicians created sophisticated works of art in intense collaboration, attempting to create an artistic and stylistic whole executed to the highest standards of craftsmanship and material authenticity. The pinnacle of the purposeful integration of all arts was the fourteenth Secession exhibition from April to June 1902, the ‘Beethoven Exhibition’…In the Beethoven exhibition, architecture, painting and sculpture came together in a coherent whole around the celebration of the life and music of the composer Ludwig van Beethoven and his Ninth Symphony in particular. Klimt’s magnificent Beethoven Frieze, the artist’s largest surviving integrated scheme, was intended as part of the Secession’s homage to the composer, represented by the Leipzig artist Max Klinger’s polychrome sculpture, which formed the centrepiece of the show. The Secession deliberately set out to realize an ambitious scheme that fully utilized painting and sculpture in a carefully designed interior space devoted to the worship of the artistic genius of Beethoven.’

Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze was situated in one of the two wings of the Secession building, placed within a staging designed by the architect Josef Hoffman, and was comprised of two long side walls and a short end wall. Running along the top of all three walls, the frieze measures just over two metres in height and is some thirty-four metres long. The elaborate allegorical narrative of the frieze, intended to be read from left to right, depicted a series of figures representing, as one scholar has noted, ‘humanity’s journey and struggle against adversity in its yearning for happiness with the eventual triumphant wish for fulfilment expressed in communal joy...Klimt’s Friezerepresents an idiosyncratic homage to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in which the artist interprets a musical piece through a highly inventive and imaginative visual narrative.’

As Rainer Metzger has noted of Klimt’s preparatory process for the Beethoven Frieze, ‘a large number of studio sketches were produced that explored the individual figures and groups of the Beethoven Frieze, the male and the female, the young and the old. Klimt applied the casein paint directly to the plaster on the basis of this collection of materials. The drawings were put on paper in full knowledge of their subsequent use, many of them including poses that can be found on the wall. The figures are often shown as very compact silhouettes or clearly outlined shapes, in the same way that they appear on the large surface of the frieze. These preliminary drawings had a very specific purpose, and the fact that they were to be included in a frieze was already implicit in their form. This gives them a concision and self-containedness that other drawings lack.’

In her catalogue raisonné of Klimt’s drawings, Alice Strobl suggested that the present sheet contains the artist’s first ideas for the nude figure of ‘Gnawing Sorrow’ (‘Nagender Kummer’) in the Beethoven Frieze. Neither figure was used in the final work, however, although the standing figure may have been referred to a year or so later, when Klimt was developing the poses of the criminals in the canvas of Jurisprudence painted for the ceiling of the great hall of the University of Vienna between 1903 and 1907; a work destroyed during the Second World War.

The first owner of the present sheet was the Viennese industrialist and art collector August Lederer (1857-1936). The second wealthiest family in Vienna, after the Rothschilds, the Lederers assembled a superb art collection, mostly devoted to artists of the Vienna Secession. August Lederer, his wife Serena and eldest son Erich were also the most important patrons and collectors of Gustav Klimt’s work. They owned some twenty paintings by Klimt, including the Beethoven Frieze fresco, as well as numerous drawings, although much of their collection of paintings was destroyed during the Second World War. As Christian Nebehay has noted, ‘Special mention must be made of the Klimt drawings in the Lederer Collection, which fortunately survived the chaos of the war years. One could justly claim that this collection is, for sheer quality, the finest known. We find here, selected by a discriminating taste, a large number of Klimt’s most notable drawings.’

As Tobias Natter has noted of the origins of the Beethoven Frieze project, ‘The development of the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk – or total work of art – and its realization in a number of exhibitions and architectural schemes can possibly be considered the most significant achievement of the artistic revolution in Vienna around 1900. Artists, architects and designers as well as poets, dramatists and musicians created sophisticated works of art in intense collaboration, attempting to create an artistic and stylistic whole executed to the highest standards of craftsmanship and material authenticity. The pinnacle of the purposeful integration of all arts was the fourteenth Secession exhibition from April to June 1902, the ‘Beethoven Exhibition’…In the Beethoven exhibition, architecture, painting and sculpture came together in a coherent whole around the celebration of the life and music of the composer Ludwig van Beethoven and his Ninth Symphony in particular. Klimt’s magnificent Beethoven Frieze, the artist’s largest surviving integrated scheme, was intended as part of the Secession’s homage to the composer, represented by the Leipzig artist Max Klinger’s polychrome sculpture, which formed the centrepiece of the show. The Secession deliberately set out to realize an ambitious scheme that fully utilized painting and sculpture in a carefully designed interior space devoted to the worship of the artistic genius of Beethoven.’

Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze was situated in one of the two wings of the Secession building, placed within a staging designed by the architect Josef Hoffman, and was comprised of two long side walls and a short end wall. Running along the top of all three walls, the frieze measures just over two metres in height and is some thirty-four metres long. The elaborate allegorical narrative of the frieze, intended to be read from left to right, depicted a series of figures representing, as one scholar has noted, ‘humanity’s journey and struggle against adversity in its yearning for happiness with the eventual triumphant wish for fulfilment expressed in communal joy...Klimt’s Friezerepresents an idiosyncratic homage to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in which the artist interprets a musical piece through a highly inventive and imaginative visual narrative.’

As Rainer Metzger has noted of Klimt’s preparatory process for the Beethoven Frieze, ‘a large number of studio sketches were produced that explored the individual figures and groups of the Beethoven Frieze, the male and the female, the young and the old. Klimt applied the casein paint directly to the plaster on the basis of this collection of materials. The drawings were put on paper in full knowledge of their subsequent use, many of them including poses that can be found on the wall. The figures are often shown as very compact silhouettes or clearly outlined shapes, in the same way that they appear on the large surface of the frieze. These preliminary drawings had a very specific purpose, and the fact that they were to be included in a frieze was already implicit in their form. This gives them a concision and self-containedness that other drawings lack.’

In her catalogue raisonné of Klimt’s drawings, Alice Strobl suggested that the present sheet contains the artist’s first ideas for the nude figure of ‘Gnawing Sorrow’ (‘Nagender Kummer’) in the Beethoven Frieze. Neither figure was used in the final work, however, although the standing figure may have been referred to a year or so later, when Klimt was developing the poses of the criminals in the canvas of Jurisprudence painted for the ceiling of the great hall of the University of Vienna between 1903 and 1907; a work destroyed during the Second World War.

The first owner of the present sheet was the Viennese industrialist and art collector August Lederer (1857-1936). The second wealthiest family in Vienna, after the Rothschilds, the Lederers assembled a superb art collection, mostly devoted to artists of the Vienna Secession. August Lederer, his wife Serena and eldest son Erich were also the most important patrons and collectors of Gustav Klimt’s work. They owned some twenty paintings by Klimt, including the Beethoven Frieze fresco, as well as numerous drawings, although much of their collection of paintings was destroyed during the Second World War. As Christian Nebehay has noted, ‘Special mention must be made of the Klimt drawings in the Lederer Collection, which fortunately survived the chaos of the war years. One could justly claim that this collection is, for sheer quality, the finest known. We find here, selected by a discriminating taste, a large number of Klimt’s most notable drawings.’

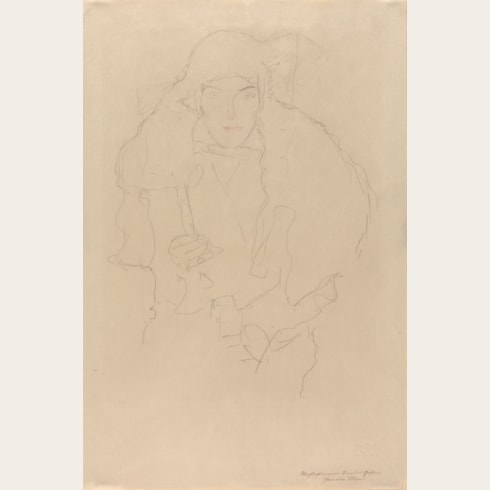

Gustav Klimt was one of the foremost draughtsmen of the early 20th century. Over four thousand drawings by him are known today, the vast majority of which are drawn in black chalk or pencil, and occasionally in coloured pencils, as well as, more rarely, pen and ink. Many more drawings have been lost, however; the artist is known to have often thrown away his drawings, while some fifty sketchbooks were destroyed in a fire in 1945. Klimt regarded his drawings purely as working studies, and thus never sold them, although he would occasionally give some away. When a sheet left his studio in this way he would invariably sign it, but otherwise he rarely signed his drawings.

As has been noted, after about 1900 Klimt’s drawings ‘are almost exclusively of the human body, mostly rapid sketches in which he recorded a certain posture or detail of movement…The drawings were done very rapidly, and Klimt does not appear to have valued them once they had fulfilled their purpose.’ That Klimt did not regard his drawings too highly is seen in an anecdote recounted by the artist’s friend, the Austrian art critic Arthur Rössler: ‘Klimt valued this abundant evidence of his industrious and penetrating study of nature only as means to an end, and he destroyed thousands of leaves when they had fulfilled their purpose, or if they failed to combine maximum expressiveness with the application of a minimum of technique. On one occasion when I was sitting with Klimt, leafing through a heap of five hundred or so [drawings], surrounded by eight or nine cats meowing or purring, which chased each other around so the rustling leaves flew through the air, I asked him in astonishment why he let them carry on like that, spoiling hundreds of the best drawings. Klimt answered, “No matter if they crumple or tear a few of the leaves – they piss on the others and that’s the best fixative!”’

The Klimt scholar Marian Bisanz-Prakken has written of the artist that ‘His intensive study of the human – primarily the female – figure centred on the individual…Klimt drew obsessively, subjecting himself to a highly disciplined approach. He usually worked from life, whereby he would subordinate the models’ poses and gestures to an overarching design…As a creative draughtsman, Klimt was a law unto himself; as a result, the body of his works on paper is so rich and comprehensive that it must be viewed as a parallel universe, existing alongside his painterly oeuvre.’

As has been noted, after about 1900 Klimt’s drawings ‘are almost exclusively of the human body, mostly rapid sketches in which he recorded a certain posture or detail of movement…The drawings were done very rapidly, and Klimt does not appear to have valued them once they had fulfilled their purpose.’ That Klimt did not regard his drawings too highly is seen in an anecdote recounted by the artist’s friend, the Austrian art critic Arthur Rössler: ‘Klimt valued this abundant evidence of his industrious and penetrating study of nature only as means to an end, and he destroyed thousands of leaves when they had fulfilled their purpose, or if they failed to combine maximum expressiveness with the application of a minimum of technique. On one occasion when I was sitting with Klimt, leafing through a heap of five hundred or so [drawings], surrounded by eight or nine cats meowing or purring, which chased each other around so the rustling leaves flew through the air, I asked him in astonishment why he let them carry on like that, spoiling hundreds of the best drawings. Klimt answered, “No matter if they crumple or tear a few of the leaves – they piss on the others and that’s the best fixative!”’

The Klimt scholar Marian Bisanz-Prakken has written of the artist that ‘His intensive study of the human – primarily the female – figure centred on the individual…Klimt drew obsessively, subjecting himself to a highly disciplined approach. He usually worked from life, whereby he would subordinate the models’ poses and gestures to an overarching design…As a creative draughtsman, Klimt was a law unto himself; as a result, the body of his works on paper is so rich and comprehensive that it must be viewed as a parallel universe, existing alongside his painterly oeuvre.’

Provenance

August Lederer, Vienna

By descent to his son, Erich Lederer, Vienna and Geneva

The Piccadilly Gallery, London, in 1973

Private collection.

By descent to his son, Erich Lederer, Vienna and Geneva

The Piccadilly Gallery, London, in 1973

Private collection.

Literature

London, The Piccadilly Gallery and New York, Spencer A. Samuels Gallery, Gustav Klimt, exhibition catalogue, 1973, unpaginated, no.24; Alice Strobl, Gustav Klimt: Die Zeichnungen. Vol.I: 1878-1903, Salzburg, 1980, pp.242-243, no.821, fig.821 (where dated 1902).

Exhibition

London, The Piccadilly Gallery, Gustav Klimt, 1973, no.24.