Gustav KLIMT

(Vienna 1862 - Vienna 1918)

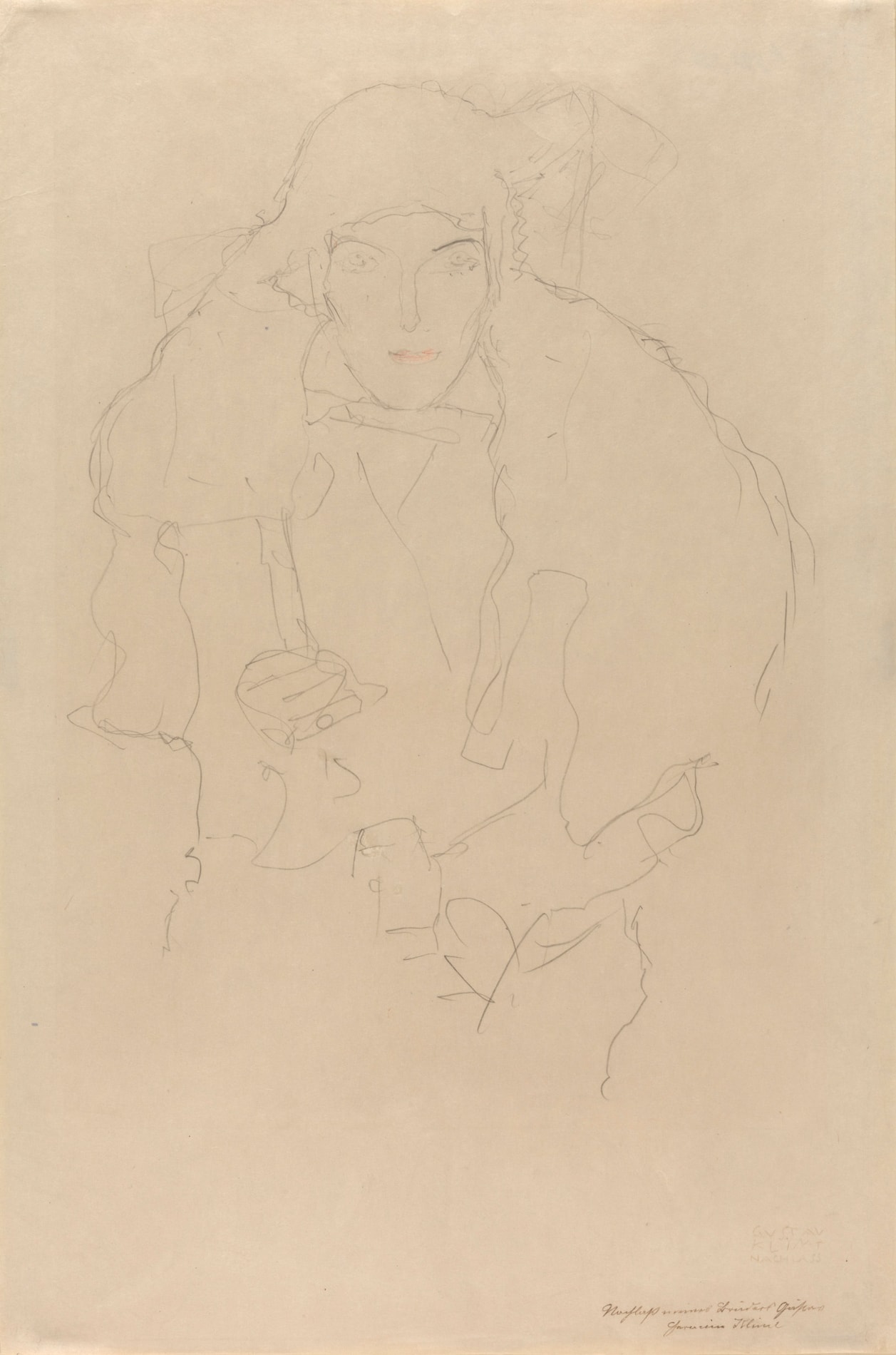

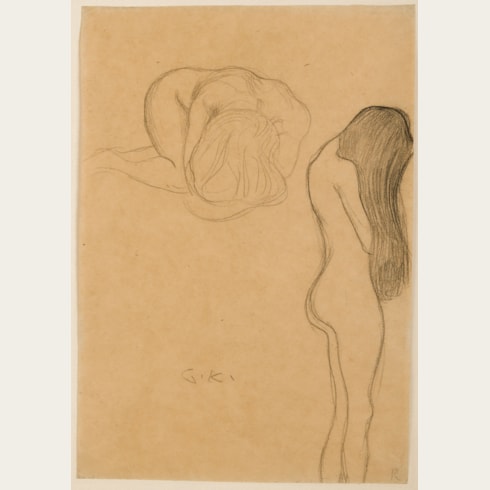

Portrait of a Woman

Sold

Pencil, with touches of red chalk.

Inscribed (by the artist’s sister Hermine Klimt) Nachlass meines Bruders Gustav / Hermine Klimt at the lower right.

565 x 370 mm. (22 1/4 x 14 1/2 in.)

Inscribed (by the artist’s sister Hermine Klimt) Nachlass meines Bruders Gustav / Hermine Klimt at the lower right.

565 x 370 mm. (22 1/4 x 14 1/2 in.)

This large drawing is closely related to an unfinished, bust-length oil portrait by Gustav Klimt of an unknown woman [see comparative image], painted around 1917-1918, towards the end of the artist’s life. One of several incomplete canvases found in Klimt’s studio at the time of his sudden death in February 1918, the painting is today in the collection of the Lentos Kunstmuseum in Linz, Austria.

The Linz painting has been described as ‘one of [Klimt’s] most striking portraits of women. The ghostly blue skin tint and the intense gaze of pale yellow irises under arched brows give a disturbing Expressionist exaggeration to her features...Initially, Klimt uses the brush like a pencil on crayon on paper, freely sketching the broad outlines of the figure on canvas before turning in more detail to the facial features.’ The painting evinces something of the effect of a drawing, and sheds some insight into Klimt’s working process, notably the way in which he seems to have begun by painting the sitter’s face, while leaving much of her dress and the background only briefly worked in. The identity of the sitter of the Linz portrait, and likewise of this drawing, has, however, thus far remained a mystery.

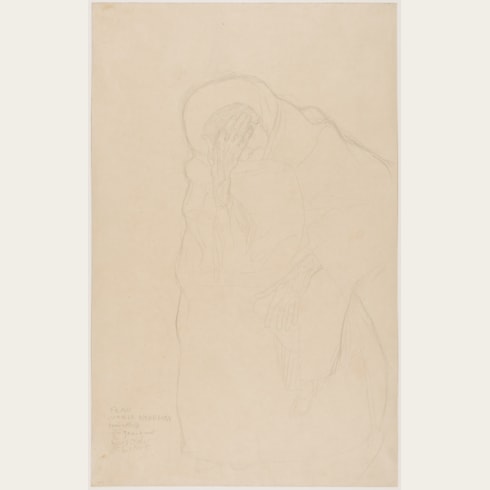

In her catalogue raisonné of Klimt’s drawings, Alice Strobl identified a handful of drawings as preparatory studies or first ideas for the Linz portrait, of which the present sheet offers perhaps the most direct comparison. One drawing related to the Linz painting is today in the Albertina in Vienna, another was formerly in the Serge Sabarsky collection in New York and was recently on the art market, while four others are in private collections. These drawings all show an unidentified woman wearing a hat, fur stole and a long dress. Some of the drawings depict the sitter either standing or sitting, which would suggest that Klimt may have originally intended the painting as a full-length composition.

As has been noted, ‘Like many of the paintings begun in the last year of Klimt’s life...the Linz Portrait of a Woman is unfinished, yet appreciated as an autonomous work of art today...Indeed, Portrait of a Woman is sufficiently realized to reflect a move by Klimt toward expressive freedom in his late portrait painting, perhaps influenced by the younger artist Egon Schiele.’

The Linz painting has been described as ‘one of [Klimt’s] most striking portraits of women. The ghostly blue skin tint and the intense gaze of pale yellow irises under arched brows give a disturbing Expressionist exaggeration to her features...Initially, Klimt uses the brush like a pencil on crayon on paper, freely sketching the broad outlines of the figure on canvas before turning in more detail to the facial features.’ The painting evinces something of the effect of a drawing, and sheds some insight into Klimt’s working process, notably the way in which he seems to have begun by painting the sitter’s face, while leaving much of her dress and the background only briefly worked in. The identity of the sitter of the Linz portrait, and likewise of this drawing, has, however, thus far remained a mystery.

In her catalogue raisonné of Klimt’s drawings, Alice Strobl identified a handful of drawings as preparatory studies or first ideas for the Linz portrait, of which the present sheet offers perhaps the most direct comparison. One drawing related to the Linz painting is today in the Albertina in Vienna, another was formerly in the Serge Sabarsky collection in New York and was recently on the art market, while four others are in private collections. These drawings all show an unidentified woman wearing a hat, fur stole and a long dress. Some of the drawings depict the sitter either standing or sitting, which would suggest that Klimt may have originally intended the painting as a full-length composition.

As has been noted, ‘Like many of the paintings begun in the last year of Klimt’s life...the Linz Portrait of a Woman is unfinished, yet appreciated as an autonomous work of art today...Indeed, Portrait of a Woman is sufficiently realized to reflect a move by Klimt toward expressive freedom in his late portrait painting, perhaps influenced by the younger artist Egon Schiele.’

Gustav Klimt was one of the foremost draughtsmen of the early 20th century. Over four thousand drawings by him are known today, the vast majority of which are drawn in black chalk or pencil, and occasionally in coloured pencils, as well as, more rarely, pen and ink. Many more drawings have been lost, however; the artist is known to have often thrown away his drawings, while some fifty sketchbooks were destroyed in a fire in 1945. Klimt regarded his drawings purely as working studies, and thus never sold them, although he would occasionally give some away. When a sheet left his studio in this way he would invariably sign it, but otherwise he rarely signed his drawings.

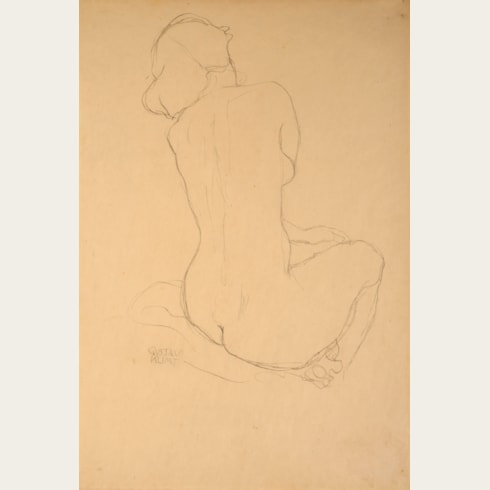

As has been noted, after about 1900 Klimt’s drawings ‘are almost exclusively of the human body, mostly rapid sketches in which he recorded a certain posture or detail of movement…The drawings were done very rapidly, and Klimt does not appear to have valued them once they had fulfilled their purpose.’ That Klimt did not regard his drawings too highly is seen in an anecdote recounted by the artist’s friend, the Austrian art critic Arthur Rössler: ‘Klimt valued this abundant evidence of his industrious and penetrating study of nature only as means to an end, and he destroyed thousands of leaves when they had fulfilled their purpose, or if they failed to combine maximum expressiveness with the application of a minimum of technique. On one occasion when I was sitting with Klimt, leafing through a heap of five hundred or so [drawings], surrounded by eight or nine cats meowing or purring, which chased each other around so the rustling leaves flew through the air, I asked him in astonishment why he let them carry on like that, spoiling hundreds of the best drawings. Klimt answered, “No matter if they crumple or tear a few of the leaves – they piss on the others and that’s the best fixative!”’

The Klimt scholar Marian Bisanz-Prakken has written of the artist that ‘His intensive study of the human – primarily the female – figure centred on the individual…Klimt drew obsessively, subjecting himself to a highly disciplined approach. He usually worked from life, whereby he would subordinate the models’ poses and gestures to an overarching design…As a creative draughtsman, Klimt was a law unto himself; as a result, the body of his works on paper is so rich and comprehensive that it must be viewed as a parallel universe, existing alongside his painterly oeuvre.’

As has been noted, after about 1900 Klimt’s drawings ‘are almost exclusively of the human body, mostly rapid sketches in which he recorded a certain posture or detail of movement…The drawings were done very rapidly, and Klimt does not appear to have valued them once they had fulfilled their purpose.’ That Klimt did not regard his drawings too highly is seen in an anecdote recounted by the artist’s friend, the Austrian art critic Arthur Rössler: ‘Klimt valued this abundant evidence of his industrious and penetrating study of nature only as means to an end, and he destroyed thousands of leaves when they had fulfilled their purpose, or if they failed to combine maximum expressiveness with the application of a minimum of technique. On one occasion when I was sitting with Klimt, leafing through a heap of five hundred or so [drawings], surrounded by eight or nine cats meowing or purring, which chased each other around so the rustling leaves flew through the air, I asked him in astonishment why he let them carry on like that, spoiling hundreds of the best drawings. Klimt answered, “No matter if they crumple or tear a few of the leaves – they piss on the others and that’s the best fixative!”’

The Klimt scholar Marian Bisanz-Prakken has written of the artist that ‘His intensive study of the human – primarily the female – figure centred on the individual…Klimt drew obsessively, subjecting himself to a highly disciplined approach. He usually worked from life, whereby he would subordinate the models’ poses and gestures to an overarching design…As a creative draughtsman, Klimt was a law unto himself; as a result, the body of his works on paper is so rich and comprehensive that it must be viewed as a parallel universe, existing alongside his painterly oeuvre.’

Provenance

The estate of the artist, with the Nachlass Gustav Klimt estate stamp (Lugt 1575) at the lower right

Possibly Gustav Nebehay, Vienna

Anonymous sale, New York, Sotheby’s, 19 April 1984, lot 6

Private collection, London.

Literature

Alice Strobl, Gustav Klimt: Die Zeichnungen. Vol.III: 1912-1918, Salzburg, 1984, pp.131-132 and p.140, no.2663 (as location unknown); Colin B. Bailey, ed., Gustav Klimt: Modernism in the Making, exhibition catalogue, Ottawa, 2001, p.224, note 5, under no.36; Alfred Weidinger, ed., Gustav Klimt, Munich, London and New York, 2007, p.307, under no.249; Tobias G. Natter, ed., Gustav Klimt: The Complete Paintings, Cologne, 2012, p.639, under no.239.