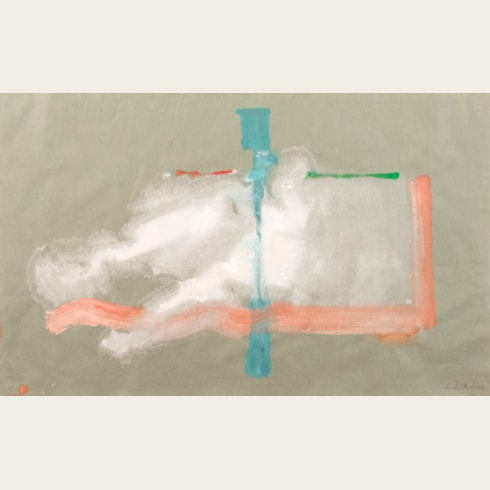

Helen FRANKENTHALER

(New York 1928 - Darien 2011)

Untitled (P94-29), 1994

Sold

Acrylic on buff paper.

Signed Frankenthaler in pencil at the lower right.

Dated Aug 94 and inscribed P94-29 in pencil on the verso.

510 x 675 mm. (20 1/8 x 26 5/8 in.)

Signed Frankenthaler in pencil at the lower right.

Dated Aug 94 and inscribed P94-29 in pencil on the verso.

510 x 675 mm. (20 1/8 x 26 5/8 in.)

As has recently been noted by one scholar, ‘Helen Frankenthaler has spoken of the intimacy of the paper medium. Her late paintings on paper embody her belief in freshness, directness, openness, and immediacy…She has used papers tinted a wide range of colors. Some pieces were executed on Japanese paper and others on very unusual lawn grass paper. Frankenthaler has utilized brushes, sponges, rubber spatulas, and scraping devices. She has thinned her pigment so that it runs and pools…With all this variety, there is a powerful and consistent sensibility. It is present in her feeling for space and form, her unique choice of colors, and in the gestural signature of her body, arm, hand, and wrist.’

Although Frankenthaler continued to create vibrant, challenging works in various media well into the 21st Century, the paintings and drawings she produced after the 1989-1990 touring retrospective of her work are somewhat less well-known than those of the previous decades. This large sheet was drawn in 1994, during a period of a decade - between 1992 and 2002 - when Frankenthaler produced very few paintings and worked almost exclusively on paper. Speaking on the occasion of an exhibition of her works on paper from the decade of the 1990s, the artist has said that ‘I get lost, whatever medium I’m working in – painting, sculpture, works on paper, graphics…for the time I am totally into creating a work. I am obsessed and the energy flows, the adrenalin flows, the ideas flow. I can’t work fast enough and that’s great. As I said before, to push is hell…I know when I started all these works on paper not too long ago, the first few felt slow and unresolved and then suddenly something clicked and I couldn’t get them out fast enough and I wanted more and more paper. Every so often I’d tear one up and my studio assistant would tremble but that’s the way it goes.’

As the critic and curator Karen Wilkin has written of Frankenthaler, ‘Over more than half a century, Frankenthaler remained a fearless explorer in the studio, investigating a remarkable range of media. She adopted acrylic paint, on canvas and paper, early on, reveling in its intensity even when thinned to a stain and in the fact that it did not produce a “halo” effect, as happened with staining with oil paint.’

In the catalogue of a recent exhibition of Frankenthaler’s work from the 1990s, the art historian Thomas Crow has written that ‘One feels that Frankenthaler…never put down a stroke or floated a wash without at least some intuition of the likely associative meanings that every such gesture would carry when conjoined with its neighbors. Her images do not fall under the heading of pleasing approximations of observed phenomena; rather, they seem truer to sense impressions, to mental events that remained inchoate until discovered in the physical action of painting and thereby lent physical form.’

Although Frankenthaler continued to create vibrant, challenging works in various media well into the 21st Century, the paintings and drawings she produced after the 1989-1990 touring retrospective of her work are somewhat less well-known than those of the previous decades. This large sheet was drawn in 1994, during a period of a decade - between 1992 and 2002 - when Frankenthaler produced very few paintings and worked almost exclusively on paper. Speaking on the occasion of an exhibition of her works on paper from the decade of the 1990s, the artist has said that ‘I get lost, whatever medium I’m working in – painting, sculpture, works on paper, graphics…for the time I am totally into creating a work. I am obsessed and the energy flows, the adrenalin flows, the ideas flow. I can’t work fast enough and that’s great. As I said before, to push is hell…I know when I started all these works on paper not too long ago, the first few felt slow and unresolved and then suddenly something clicked and I couldn’t get them out fast enough and I wanted more and more paper. Every so often I’d tear one up and my studio assistant would tremble but that’s the way it goes.’

As the critic and curator Karen Wilkin has written of Frankenthaler, ‘Over more than half a century, Frankenthaler remained a fearless explorer in the studio, investigating a remarkable range of media. She adopted acrylic paint, on canvas and paper, early on, reveling in its intensity even when thinned to a stain and in the fact that it did not produce a “halo” effect, as happened with staining with oil paint.’

In the catalogue of a recent exhibition of Frankenthaler’s work from the 1990s, the art historian Thomas Crow has written that ‘One feels that Frankenthaler…never put down a stroke or floated a wash without at least some intuition of the likely associative meanings that every such gesture would carry when conjoined with its neighbors. Her images do not fall under the heading of pleasing approximations of observed phenomena; rather, they seem truer to sense impressions, to mental events that remained inchoate until discovered in the physical action of painting and thereby lent physical form.’

Born into a life of privilege on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, the American painter, draughtsman and printmaker Helen Frankenthaler was educated at Horace Mann, Brearley and the Dalton School in New York (where her first art teacher was the Mexican painter Rufino Tamayo), before completing her studies with the painter Paul Feeley at Bennington College in Vermont. Her early work was strongly influenced by the paintings of Willem de Kooning and Arshile Gorky, as well as the earlier work of Wassily Kandinsky and Joan Miró. Soon after setting up her studio in New York in 1951 Frankenthaler became close friends with the eminent art critic Clement Greenberg, with whom she was to be in a relationship for several years. When the painter Adolph Gottlieb saw her paintings at Greenberg’s apartment, he included a work by her in his selection for a group exhibition at the Kootz Gallery in 1950. The following year Frankenthaler was the youngest artist to be included in the Ninth Street Show, an exhibition organized by members of the New York School (also known as The Club), while later that year the twenty-three-year old artist had her first solo show, of eleven paintings, at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery.

Perhaps the most significant event of this period, however, was Frankenthaler’s discovery of the work of Jackson Pollock, initially at his exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1950. Greenberg introduced her to Pollock the following year, and she began closely studying his methods on visits to his studio in Long Island. The influence of Pollock on her own paintings was to be significant. As noted by the scholar Barbara Rose, in the first published monograph devoted to Frankenthaler’s work, ‘The overt physicality of Pollock’s method, the sense of the painting having been, as Frankenthaler puts it, “choreographed”, made possible a large scale, a boldness and an openness that appealed to her.’ By the end of 1951 Frankenthaler had become a part of the vibrant artistic community in New York, although younger than almost all of her contemporaries. She became friendly with Pollock and Lee Krasner, as well as with Gottlieb, Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Franz Kline, Joan Mitchell, Barnett Newman and David Smith.

In October 1952, after a trip to Nova Scotia with Greenberg, Frankenthaler painted a monumental canvas she titled Mountains and Sea, in which her characteristic stain technique first came to the fore. The painting, the largest she had attempted up to that point, became of seminal importance in heralding the direction of the artist’s later career. She had already experimented with working on the floor rather than on a painting on an easel. Now Frankenthaler began pouring and spilling paint directly onto raw, unprimed canvas. In the spring of 1953 the older painters Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis visited Frankenthaler’s studio and came away impressed with what they had seen. The three painters were soon making regular studio visits to each other, and Frankenthaler’s work was to be an influence on Louis and Noland’s development of Color Field painting.

Frankenthaler’s work began to receive more attention as she continued to have one-man exhibitions at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery between 1953 and 1958, and also had her work included in museum shows. In 1958 she married the artist Robert Motherwell, and two years later an early retrospective exhibition of her work, curated by the poet and art critic Frank O’Hara, was mounted at the Jewish Museum in New York. By this time her paintings had been acquired by the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, while in 1959 she had been represented in the Documenta II exhibition in Kassel and biennials in Paris and São Paolo. At the age of thirty, Frankenthaler was now firmly established as one of the leading painters of the second generation of the New York school of abstract painters.

Solo gallery shows of her work - in New York, Los Angeles, Paris, London and elsewhere - continued throughout the 1960s, as did several important museum surveys in which her paintings were included. (She also occasionally taught fine art classes and seminars and gave lectures during this period.) Frankenthaler was one of three artists chosen to represent the United States at the Venice Bienniale of 1966, and in 1969 was the subject of a major retrospective exhibition at the Whitney Museum in New York; a show that later travelled to England and Germany and introduced her work to a much wider public abroad. This success continued throughout the 1970s with a number of museum and gallery exhibitions, as well as some public mural commissions, executed as paintings, ceramic tiles or tapestry. She also began working productively as a printmaker at this time, producing etchings, monotypes, lithographs and colour woodcuts; the latter in particular took up much of her time in the 1990s.

Helen Frankenthaler has said that ‘A really good picture looks as if it’s happened at once. It’s an immediate image. For my own work, when a picture looks labored and overworked, and you can read in it – well, she did this and then she did that, and then she did that – there is something in it that has not got to do with beautiful art to me. And I usually throw those out, though I think very often it takes ten of those over-labored efforts to produce one really beautiful wrist motion that is synchronized with your head and heart, and you have it, and therefore it looks as if it were born in a minute.’

Perhaps the most significant event of this period, however, was Frankenthaler’s discovery of the work of Jackson Pollock, initially at his exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1950. Greenberg introduced her to Pollock the following year, and she began closely studying his methods on visits to his studio in Long Island. The influence of Pollock on her own paintings was to be significant. As noted by the scholar Barbara Rose, in the first published monograph devoted to Frankenthaler’s work, ‘The overt physicality of Pollock’s method, the sense of the painting having been, as Frankenthaler puts it, “choreographed”, made possible a large scale, a boldness and an openness that appealed to her.’ By the end of 1951 Frankenthaler had become a part of the vibrant artistic community in New York, although younger than almost all of her contemporaries. She became friendly with Pollock and Lee Krasner, as well as with Gottlieb, Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Franz Kline, Joan Mitchell, Barnett Newman and David Smith.

In October 1952, after a trip to Nova Scotia with Greenberg, Frankenthaler painted a monumental canvas she titled Mountains and Sea, in which her characteristic stain technique first came to the fore. The painting, the largest she had attempted up to that point, became of seminal importance in heralding the direction of the artist’s later career. She had already experimented with working on the floor rather than on a painting on an easel. Now Frankenthaler began pouring and spilling paint directly onto raw, unprimed canvas. In the spring of 1953 the older painters Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis visited Frankenthaler’s studio and came away impressed with what they had seen. The three painters were soon making regular studio visits to each other, and Frankenthaler’s work was to be an influence on Louis and Noland’s development of Color Field painting.

Frankenthaler’s work began to receive more attention as she continued to have one-man exhibitions at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery between 1953 and 1958, and also had her work included in museum shows. In 1958 she married the artist Robert Motherwell, and two years later an early retrospective exhibition of her work, curated by the poet and art critic Frank O’Hara, was mounted at the Jewish Museum in New York. By this time her paintings had been acquired by the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, while in 1959 she had been represented in the Documenta II exhibition in Kassel and biennials in Paris and São Paolo. At the age of thirty, Frankenthaler was now firmly established as one of the leading painters of the second generation of the New York school of abstract painters.

Solo gallery shows of her work - in New York, Los Angeles, Paris, London and elsewhere - continued throughout the 1960s, as did several important museum surveys in which her paintings were included. (She also occasionally taught fine art classes and seminars and gave lectures during this period.) Frankenthaler was one of three artists chosen to represent the United States at the Venice Bienniale of 1966, and in 1969 was the subject of a major retrospective exhibition at the Whitney Museum in New York; a show that later travelled to England and Germany and introduced her work to a much wider public abroad. This success continued throughout the 1970s with a number of museum and gallery exhibitions, as well as some public mural commissions, executed as paintings, ceramic tiles or tapestry. She also began working productively as a printmaker at this time, producing etchings, monotypes, lithographs and colour woodcuts; the latter in particular took up much of her time in the 1990s.

Helen Frankenthaler has said that ‘A really good picture looks as if it’s happened at once. It’s an immediate image. For my own work, when a picture looks labored and overworked, and you can read in it – well, she did this and then she did that, and then she did that – there is something in it that has not got to do with beautiful art to me. And I usually throw those out, though I think very often it takes ten of those over-labored efforts to produce one really beautiful wrist motion that is synchronized with your head and heart, and you have it, and therefore it looks as if it were born in a minute.’

Provenance

Bobbie Greenfield Gallery, Santa Monica, in 1995

Bernard Jacobson Gallery, London, in 2000

Private collection, London.

Bernard Jacobson Gallery, London, in 2000

Private collection, London.

Exhibition

Santa Monica, Bobbie Greenfield Gallery, Helen Frankenthaler: Recent Prints and Paintings on Paper, 1995, unnumbered; London, Bernard Jacobson Gallery, Frankenthaler: On Paper 1990-1999, 2000, no.5.