Horst JANSSEN

(Hamburg 1929 - Hamburg 1995)

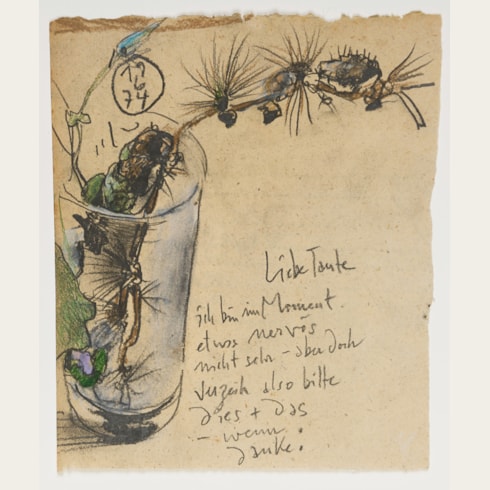

Letter to Viola Rackow, with a Still Life of a Champagne Cork and a Cigarette Butt

Dated and inscribed 14 / 7 / 77 730 / Lieb Vriederich / du hast mich immer noch nicht begriffen: / das einzigewas du mir zu sagen hast, / während du mit deinem Schlüssel in der / Hand mich aus dem wenigsten schlaf reisst, / ist: “die Kinder sind so enttäuscht – ich tu / das nicht wieder”. / das ist so widerlich egozentrisch / + so unfair – es Könnte von mir sein. / Runge. at the bottom half of the sheet.

261 x 241 mm. (10 1/4 x 9 1/2 in.) at greatest dimensions

‘Dear Vriedrich,

You still haven’t understood me: The only thing that you have to say to me, with your keys in your hand while you snatch me out of my meagre sleep, is “the children are so disappointed - I will not do this again”.

That is so disgustingly egocentric and so unfair - it could be from me.

Runge.’

Horst Janssen’s love affair with Viola Rackow (b.1941) resulted in a long friendship and correspondence, with the artist sending her numerous illustrated letters. In many of these letters, such as the present sheet, the artist addresses Viola as ‘Vriederich’ or ‘Vriedrich’ and signs himself as ‘Runge’. This stems from the fact that Janssen often went to see the important group of paintings by the German Romantic artists Philipp Otto Runge and Caspar David Friedrich in the collection of the Kunsthalle in Hamburg. His obsession with these works resulted in Viola’s once jokingly referring to him as ‘Runge’, to which Janssen responded by calling her ‘Vriederich’ (with a V for Viola instead of an F), and it seems that both nicknames stuck.

As Jutta Siegmund-Schultze has noted, ‘As can be learned from the letters, Horst Janssen loved Viola – ‘your agility, your verve, your serenity + nimbleness’ or, as it says in a beautiful folk-song-like passage: ‘...I love you / I love your little face / I love you / I love your sweet little face / I love you /I love your body / excessively. / YES’. But the other side of the coin is: ‘You are still too young for me in your development. You do not yet have a relationship with the painfulness of life…’ [or] ‘I love you and it is hopeless for my longing.’ Conclusion: ‘You’re a pretty tough cookie, and I love you very much.’ In this relationship, in which Janssen, perhaps for the first time, not only has a loving, tender woman, but also a worthy opponent, it goes without saying that sometimes the sparks fly, that fights are called for, that jealousy and misunderstandings accumulate, which cannot be avoided given the equally distributed temperament of the two. But it's also touching to read how Janssen keeps trying to understand and educate Viola, to clear up these damned misunderstandings and put things in order, especially with himself, and to find the serenity that he so desperately needs and which means the truth to him. These letters to Viola are not only the very personal testimony of a love between two extraordinary people, they also provide an insight into the life of one of the greatest artists of our time, into his struggles against himself and his ailing body, into his longings and fears, which always revolve around creativity and the end of everything, death, and for which, just as much as for his joy on a beautiful morning, he needs his beloved to listen and to be ‘at peace’ with everything.’

The German draughtsman, illustrator and printmaker Horst Janssen was raised in the city of Oldenburg by his mother and grandparents, and never knew his father. Between 1946 and 1951 he studied at the Landeskunstschule in Hamburg, where his teacher was the painter and engraver Alfred Mahlau. (He was later offered a professorship at the Hamburg academy, but turned down the opportunity.) In 1948 he published a children’s book and in the early 1950s began developing his skills as a printer and lithographer.

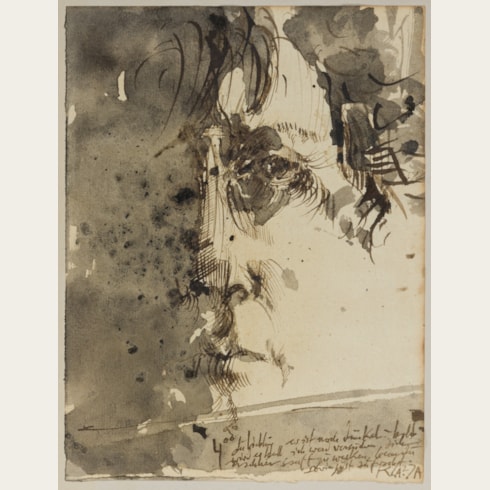

Hugely prolific, Janssen produced a large number of drawings, etchings, lithographs, woodcuts and wood engravings characterized by dreamlike and often erotic imagery, creating a distinctive body of work – landscapes, still life subjects, portraits and self-portraits, often incorporating literary references and texts - that was quite unusual within the context of postwar European art. In the early part of his career he rarely exhibited his work outside Hamburg, and if he sold a print or drawing it was usually for a relatively modest amount – between 50 and 100 Marks for a print and between 200 and 850 Marks for a drawing – to a small coterie of collectors whom he knew. As he said at around this time, ‘I want to know who has my pictures. Out of vanity. Besides, I love them.’

Janssen’s first retrospective exhibition of almost 180 drawings and prints was held in 1965 at the Kestner-Gesellschaft in Hanover, leading the director of that institution, Wieland Schmied, to describe the artist as ‘the greatest draughtsman apart from Picasso. But Picasso is a different generation.’ The exhibition later travelled to several cities in Germany and also to Basel, and led to Janssen’s work becoming much more widely known outside Hamburg.

His output never slackened, and his intensely personal vision continued to find new avenues of expression. He also often created drawings and prints inspired by foreign works of art, and in 1972 published an appreciation of the printed landscapes of the 19th century Japanese artist Hokusai. During his lifetime, Janssen won several important prizes and awards – including the first prize for graphic art at the Venice Biennale of 1968 - and his drawings and prints were widely exhibited throughout Europe, as well as in America, Russia and Japan. Significant exhibitions of his work were held in Mannheim in 1976, at the Documenta VI in Kassel the following year, at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1980 and the Albertina in Vienna in 1982. Janssen died in Hamburg in 1995, at the age of sixty-five. Five years later the Horst Janssen Museum in the artist’s hometown of Oldenburg, dedicated to the artist’s work, was inaugurated.

Provenance

By descent to Nicolaus Rackow, Eppendorf, Hamburg.

Literature