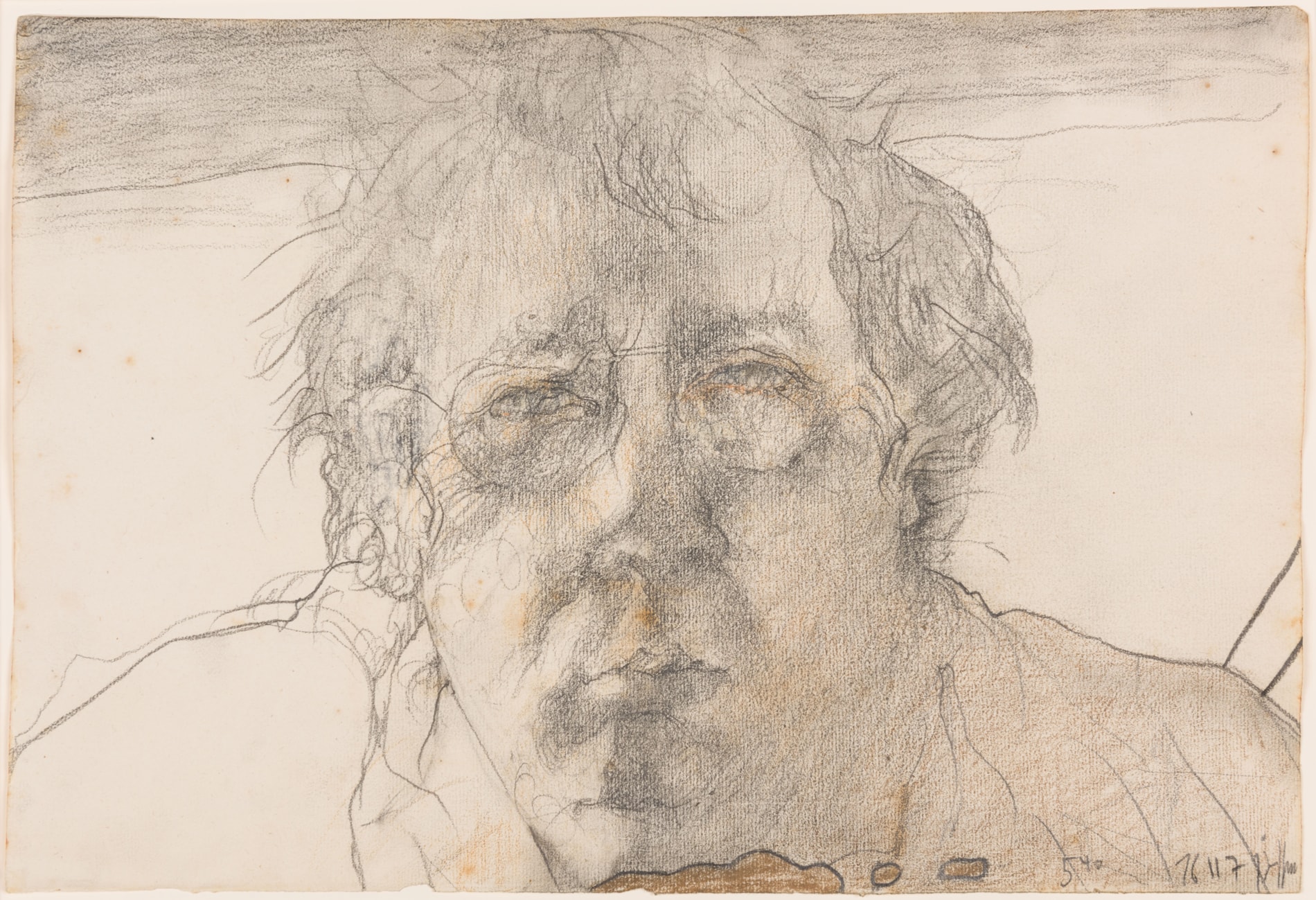

Horst JANSSEN

(Hamburg 1929 - Hamburg 1995)

Self-Portrait

Inscribed 5.40, and signed and dated 16 11 71 Janssen at the lower right.

Inscribed 96 / Fest on the verso.

261 x 382 mm. (10 1/4 x 15 in.)

Drawn on the 16th of November 1971, the present sheet may be related to a similar self-portrait drawing of about the same date, today in a private collection in London, which is the artist’s design for the poster for an exhibition of his prints at the Galerie Kornfeld in Zurich in November 1971. Another closely comparable self-portrait drawing, dated 10 March 1972 and also depicting the artist’s then-lover Gesche Tietjens, is in a different private collection.

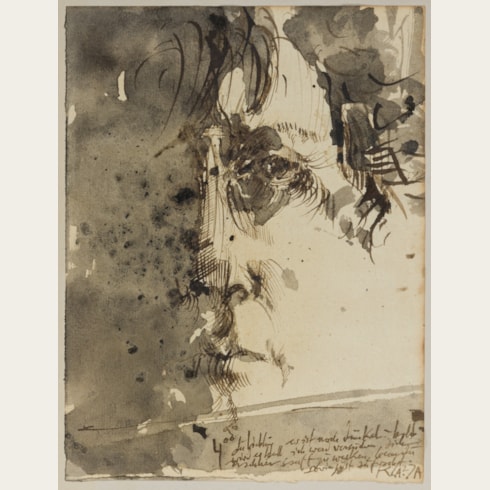

As Janssen himself wrote, in the introduction to the catalogue of an exhibition of his work in 1970, ‘Well – I was born, I played, I was filled with wisdom and now I sit here and draw; drawings for the market, drawings for presents, self portrait-drawings and drawings of every kind…I achieve the greatest effect however in the drawings of the third category – the self portraits. Partly because this discipline is hardly cultivated at all these days, partly because a comedian-like gift puts me in the position of being able to make my face appear quite convincingly, according to requirements, sometimes gay and young, sometimes melancholic, sometimes wild, and at other times bloated to the point of being destroyed, yet directly stimulating. My drawing ability in portraying the actual mirror image in a very exact manner, but with the very unusual yet important understatement, thus created the impression of that honesty so much desired by the public.’

The artist further described the process of making a self-portrait drawing: ‘So I sit down in the morning under the lamp when it is still dark and look across at myself for a moment: the right side of my face in reflection is shadowed. A light-hearted mischievousness does not make me see the most intense darkness a little to the right of the right extremity of the reflection of my face, where the most intense darkness actually is, but in the middle of the same to the right next to the nose, and the top and bottom lips running into the nick of the chin. The left eye strikes me as being quiet, soft and large because its gaze is not fixed on any one object. From this moment on I have to be careful not to destroy this completely ‘Nazarene’ expression, by not looking at my reflection too penetratingly or by not making it grin by remembering a joke. This can only happen as a form of recovery after the fixing of a momentary image. Once this has happened, the two of us can allow ourselves a coffee, a cigarette and a short chat to recover, which affords us considerable pleasure since we have the same needs and pleasures in everything. In the ensuing period the already determined concept is filled in quasi-automatically. From time to time I glance across at him seeking correction or merely confirmation and he glances back to me, showing a sympathetic understanding for my intentions. Thus this tender portrait comes to an end by itself, in this corresponding hour of the morning. I also put a crude signature underneath just of figures indicating the time – like a concluding farewell as an emphatic ending to a successful and clarifying discussion. And then a few seconds afterwards, when I am alone, I laugh out loud: Duped. And the day can begin.’

The present sheet once belonged to the artist’s close friend, the German historian, editor and critic Joachim Fest (1926-2006), who knew Janssen for over twenty-five years and assembled a large collection of his graphic work. Best known for his writings on the Nazi era, Fest also served as culture editor of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung between 1973 and 1993. Fest published two books on the artist; the first, Horst Janssen: Selbstbildnis von fremder Hand, appeared in 2001 and was followed five years later by Die schreckliche Lust des Auges: Erinnerungen an Horst Janssen, a memoir of their long friendship.

The German draughtsman, illustrator and printmaker Horst Janssen was raised in the city of Oldenburg by his mother and grandparents, and never knew his father. Between 1946 and 1951 he studied at the Landeskunstschule in Hamburg, where his teacher was the painter and engraver Alfred Mahlau. (He was later offered a professorship at the Hamburg academy, but turned down the opportunity.) In 1948 he published a children’s book and in the early 1950s began developing his skills as a printer and lithographer.

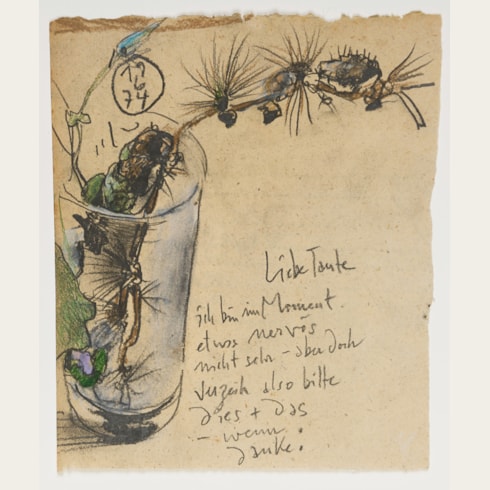

Hugely prolific, Janssen produced a large number of drawings, etchings, lithographs, woodcuts and wood engravings characterized by dreamlike and often erotic imagery, creating a distinctive body of work – landscapes, still life subjects, portraits and self-portraits, often incorporating literary references and texts - that was quite unusual within the context of postwar European art. In the early part of his career he rarely exhibited his work outside Hamburg, and if he sold a print or drawing it was usually for a relatively modest amount – between 50 and 100 Marks for a print and between 200 and 850 Marks for a drawing – to a small coterie of collectors whom he knew. As he said at around this time, ‘I want to know who has my pictures. Out of vanity. Besides, I love them.’

Janssen’s first retrospective exhibition of almost 180 drawings and prints was held in 1965 at the Kestner-Gesellschaft in Hanover, leading the director of that institution, Wieland Schmied, to describe the artist as ‘the greatest draughtsman apart from Picasso. But Picasso is a different generation.’ The exhibition later travelled to several cities in Germany and also to Basel, and led to Janssen’s work becoming much more widely known outside Hamburg.

His output never slackened, and his intensely personal vision continued to find new avenues of expression. He also often created drawings and prints inspired by foreign works of art, and in 1972 published an appreciation of the printed landscapes of the 19th century Japanese artist Hokusai. During his lifetime, Janssen won several important prizes and awards – including the first prize for graphic art at the Venice Biennale of 1968 - and his drawings and prints were widely exhibited throughout Europe, as well as in America, Russia and Japan. Significant exhibitions of his work were held in Mannheim in 1976, at the Documenta VI in Kassel the following year, at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1980 and the Albertina in Vienna in 1982. Janssen died in Hamburg in 1995, at the age of sixty-five. Five years later the Horst Janssen Museum in the artist’s hometown of Oldenburg, dedicated to the artist’s work, was inaugurated.

Provenance

Anonymous sale, Berlin, Villa Grisebach, 31 May 2012, lot 48

Bernd Schultz, Berlin.