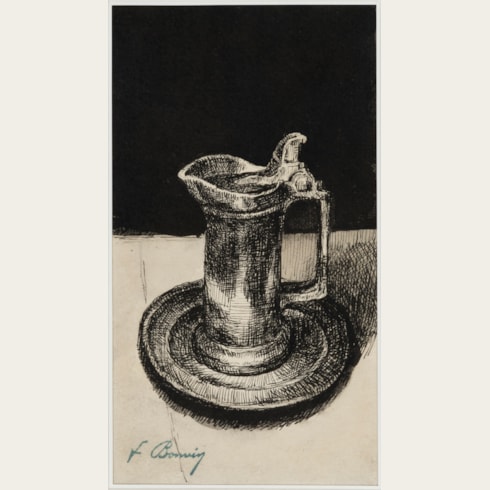

François BONVIN

(Vaugirard 1817 - Saint-Germain-en-Laye 1887)

A Standing Man Holding a Jug

Sold

Black, red and white chalk.

Signed and dated 76. f. Bonvin at the lower right.

201 x 142 mm. (7 7/8 x 5 5/8 in.)

Signed and dated 76. f. Bonvin at the lower right.

201 x 142 mm. (7 7/8 x 5 5/8 in.)

Dated 1876, the present sheet is a fine and typical example of the sort of finished drawing that the artist would have intended for sale. As has been noted of this period of François Bonvin’s career, ‘The year 1876 was difficult for the artist, who lost family (his step-mother, Adélaïde Beurier, and his half-brother, Antoine), and his friends [the] painters [Eugène] Fromentin and [Narcisse Virgilio] Diaz. He has several serious flare-ups of his kidney stones, especially in the summer of that year…However, there were also lighter moments in the midst of his gloom. He attended several cheerful meals reuniting old friends…There were some excursions, giving rise to charming scenes… Above all, there was as ‘a nice little success’ with the two paintings sent to the Salon of 1876, two landscapes, or rather, seascapes…the first purchased by Lefebvre, the second by Valancourt, a new friend.’

Stylistically comparable drawings by Bonvin of the same date include several figure studies - two in the Louvre, one in the Cleveland Museum of Art and one in a private collection - for the now-lost painting Le couvreur tombé (scène d’hôpital), and it is possible that the present sheet may be related to the same composition.

Le couvreur tombé (The Fallen Roofer) was the only painting Bonvin sent to the Salon of 1877, and no image of the work survives. Indeed, its composition is known only from a description of it in the 1888 sale catalogue of the collection of its first owner, the artist’s friend and neighbour M. Seure, who came to own over fifty paintings by Bonvin. Gabriel Weisberg describes Le couvreur tombé as ‘a multi-figured composition [which] records an accident which has befallen a worker at the moment when, surrounded by companions and gawkers, lying on a stretcher, he is receiving first aid from a doctor.’

What may be a small compositional sketch for the lost painting, signed and dated 1877, that was recently on the art market.

Stylistically comparable drawings by Bonvin of the same date include several figure studies - two in the Louvre, one in the Cleveland Museum of Art and one in a private collection - for the now-lost painting Le couvreur tombé (scène d’hôpital), and it is possible that the present sheet may be related to the same composition.

Le couvreur tombé (The Fallen Roofer) was the only painting Bonvin sent to the Salon of 1877, and no image of the work survives. Indeed, its composition is known only from a description of it in the 1888 sale catalogue of the collection of its first owner, the artist’s friend and neighbour M. Seure, who came to own over fifty paintings by Bonvin. Gabriel Weisberg describes Le couvreur tombé as ‘a multi-figured composition [which] records an accident which has befallen a worker at the moment when, surrounded by companions and gawkers, lying on a stretcher, he is receiving first aid from a doctor.’

What may be a small compositional sketch for the lost painting, signed and dated 1877, that was recently on the art market.

Born into poverty, François Bonvin studied at the Ecole de Dessin in Paris between 1828 and 1830, but had to abandon his studies to begin work as a typesetter and printer. His earliest known works date from the late 1830’s, by which time Bonvin was also working as a police clerk. He eventually returned to his studies at the Ecole de Dessin – a school geared primarily towards the decorative arts - and in 1843 began attending life-drawing classes at the Académie Suisse. Around this time he met his mentor, the painter François-Marius Granet, who encouraged him to study 17th century Dutch and Flemish painting as a way of refining his approach to genre subjects. Perhaps with the support of Granet, who was on the jury, Bonvin made his Salon debut in 1847, and he continued to show there until 1880, earning a particular reputation as a painter of genre and interior scenes and still-lifes.

Bonvin rose to become one of the leaders of a group of Realist painters in 19th century France who found inspiration in subjects and scenes taken from contemporary urban life. Many of the models for his drawings and paintings seem to have been habitués of the inn owned by his father in Vaugirard. In 1859 a number of his paintings were accepted for exhibition at the Salon, though Realist works by such friends and colleagues as Henri Fantin-Latour, Alphonse Legros, Théodule Ribot and James McNeill Whistler were rejected. As a result, Bonvin invited these artists to exhibit their rejected works at his studio, known as the Atelier Flamand, an offer repeated after the Salon of 1863. Later that year his wife left him, and Bonvin found it difficult to concentrate on his paintings, preferring instead to make numerous drawings. In his final years he grew blind and suffered from paralysis. Although a retrospective exhibition of his work was held in 1886, followed a few months later by a benefit auction intended to raise funds for a pension for the artist, Bonvin died in impoverished circumstances in 1887.

Bonvin’s modern reputation rests largely on his drawings. His first dated works were executed in 1845 and 1846, while he still worked as a civil servant. At this time he would exhibit his drawings informally under the arcades of the Institut de France, and it was there that he met his first significant patron, Louis Laperlier. At the start of his artistic career Bonvin would not be able to afford models, and would often make use of friends and their families as models, as well as washerwomen, cooks, nuns, children, peasants and beggars.

Provenance

Probably Gustave Tempelaere, Paris

Galerie F. & J. Tempelaere, Paris

Paul Brandt, Amsterdam, in 1977.

Galerie F. & J. Tempelaere, Paris

Paul Brandt, Amsterdam, in 1977.

Exhibition

Laren, Singer Museum, 19e en 20e eeuwse Franse kunst: aquarellen en tekeningen uit de collectie Paul Brandt, Amsterdam, 1977, no.5.