Adolf HIREMY-HIRSCHL

(Temesvár 1860 - Rome 1933)

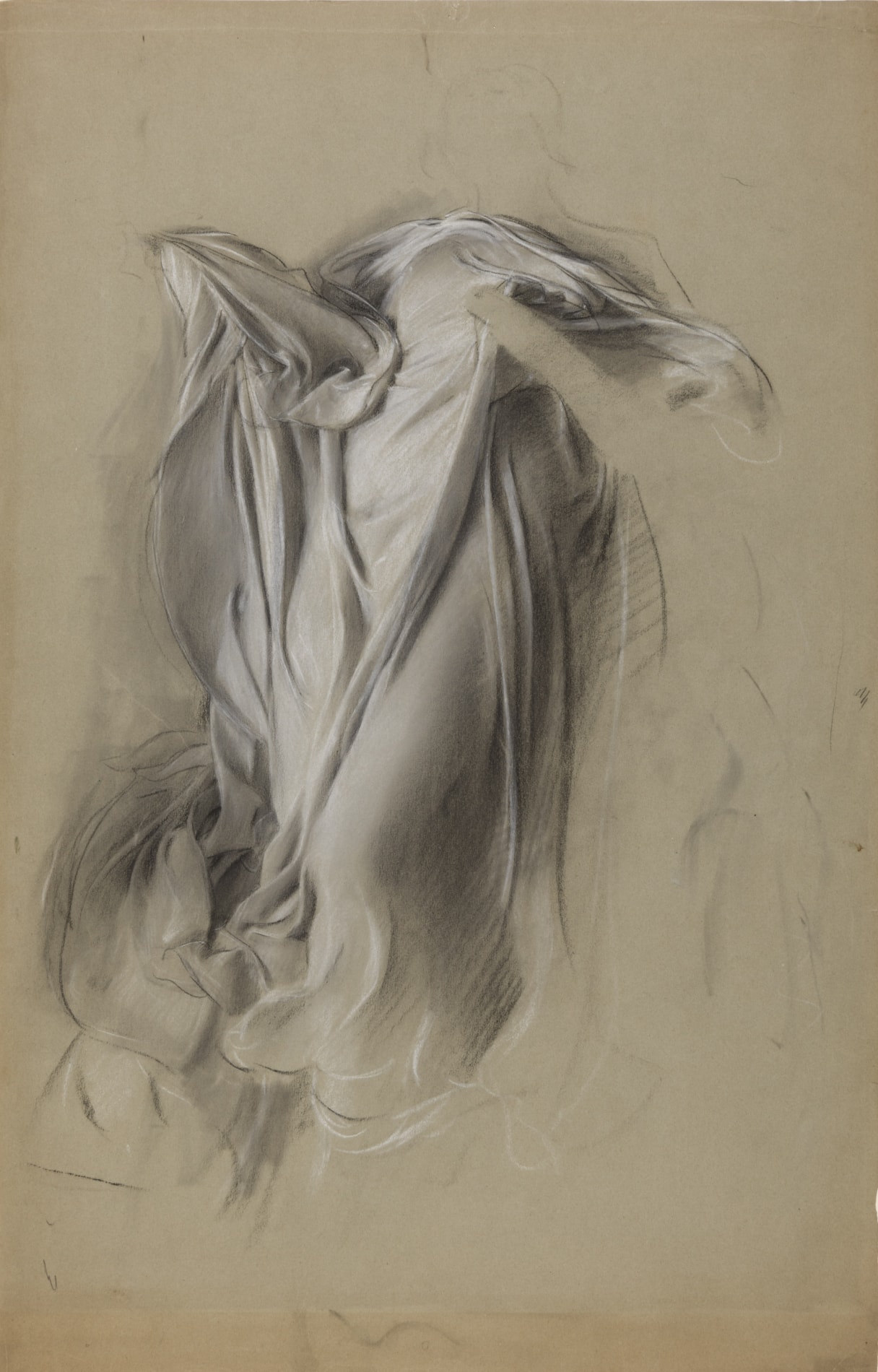

Drapery Study

Sold

Black and white chalk, with stumping, on blue-grey paper.

531 x 339 mm. (20 7/8 x 13 3/8 in.) [sheet]

531 x 339 mm. (20 7/8 x 13 3/8 in.) [sheet]

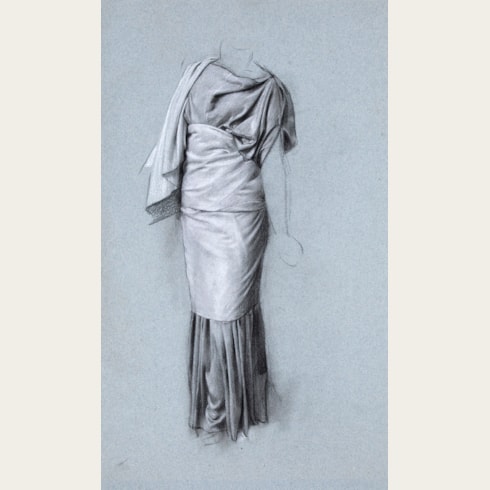

The present sheet may be a study for one of the draped women in Adolf Hirémy-Hirschl’s now-lost painting of A Wedding Procession in Ancient Rome, completed in 1891. The painting depicts the moments before a classical wedding, when the bride is led to the house of the bridegroom, accompanied by bridesmaids singing hymns to the god Hymeneus. A contemporary critic described the painting: ‘Another reminiscence of antique Rome…The bride, surrounded by her friends, who are singing, playing, and making merry, is being led to her new home. Here, too, all the figures are life-size, and here again the natural atmosphere accords with the scene being enacted under its canopy.’ The painting won the ‘Kaiserpreis’; a prize awarded by the Künstlerhaus in Vienna when it was exhibited there in 1891, and was also shown in the same year in Berlin. A smaller, closely-related drapery study was exhibited in Rome in 1981.

Drawings such as the present sheet are a testament to Hirémy-Hirschl’s skill as a draughtsman. As one scholar has written of another, similar drapery study by the artist, ‘the subtle irregularity of the fluted and swirling forms…produce an extraordinary sculptural effect, as of the crispest marble carving of the Parthenon pediment figures. And, in a similar way, the curves and flutings of the drapery suggest rather than explicitly articulate the firm of the body beneath: The artist gives an organic coherency to the drapery composition that does not so much reveal the body as provide a formal analogue to it. The construction of pleats and folds out of both whites and darker tones is wonderfully expert and has an energetic amplitude of form that recalls some of the finest drapery studies of Ingres or Tissot. We may never come to think, overall, of Hirémy-Hirschl as a great master, but among his drawings there are true masterpieces, any one of which a great master would be happy to claim.’

The present sheet, together with the rest of the contents of Hirémy-Hirschl’s studio in Rome, remained in the possession of the artist’s descendants for many years after his death. This large cache of drawings, watercolours, pastels and oil sketches was only dispersed in the early 1980s.

Drawings such as the present sheet are a testament to Hirémy-Hirschl’s skill as a draughtsman. As one scholar has written of another, similar drapery study by the artist, ‘the subtle irregularity of the fluted and swirling forms…produce an extraordinary sculptural effect, as of the crispest marble carving of the Parthenon pediment figures. And, in a similar way, the curves and flutings of the drapery suggest rather than explicitly articulate the firm of the body beneath: The artist gives an organic coherency to the drapery composition that does not so much reveal the body as provide a formal analogue to it. The construction of pleats and folds out of both whites and darker tones is wonderfully expert and has an energetic amplitude of form that recalls some of the finest drapery studies of Ingres or Tissot. We may never come to think, overall, of Hirémy-Hirschl as a great master, but among his drawings there are true masterpieces, any one of which a great master would be happy to claim.’

The present sheet, together with the rest of the contents of Hirémy-Hirschl’s studio in Rome, remained in the possession of the artist’s descendants for many years after his death. This large cache of drawings, watercolours, pastels and oil sketches was only dispersed in the early 1980s.

Born in the Hungarian town of Temesvár, Adolf Hirschl was raised in Vienna, where in 1878 he obtained a scholarship to the Akademie der bildenden Künste. In 1880 his first major canvas, Farewell: Scene from Hannibal Crossing the Alps, won a prize for historical painting. This was followed two years later by a second prize that allowed him to visit Rome, where he lived until 1884. His experiences in Rome were to have a profound effect on his work, notably in his preference for scenes from ancient Roman history. On his return to Vienna Hirschl exhibited a large canvas of The Plague in Rome, painted in 1884, to considerable acclaim. He soon established a successful career as a painter, receiving numerous commissions and producing grand, complex compositions of historical or allegorical subjects that were widely praised by critics and connoisseurs. Dramatic subjects such as Ahasuerus at the End of the World, painted around 1888, reveal another aspect of the artist’s imaginative approach to subject and composition. Hirschl’s paintings were exhibited throughout Europe, and the artist reached the peak of his Viennese career when he won the Imperial Prize in 1891. Despite his status as one of the leading artists in fin-de-siècle Vienna, as the turn of the century approached his work began to be overshadowed by the more progressive and radical paintings of Gustav Klimt and the artists of the Vienna Secession movement.

In 1898 Hirschl married an Austrian-born Englishwoman who divorced her husband to marry him; the wedding scandalized polite society in Vienna and led the artist to sever his links with the city. Adopting the Hungarian name Hirémy, he soon afterwards moved to Rome, where he spent the last thirty-five years of his career, and where a retrospective exhibition of seventy of his works was held in 1904. Four years later, in 1908, his painting of Souls on the Banks of the Acheron, painted a decade earlier in 1898, was exhibited at the Imperial Jubilee exhibition in Vienna, where it was purchased by the state.

An eminent member of the expatriate artistic community in Rome, Hirémy-Hirschl was admitted into the Accademia di San Luca in 1911. He remained largely immune to the latest avant-garde trends in art, both in Vienna and in Rome, preferring to work in his own distinctive manner. As one contemporary critic wrote, ‘He is a very hard as well as a very scrupulous worker, and one who goes on his own way undaunted, never imitating or letting himself be influenced by what others are doing.’1 Unfortunately, a number of the artist’s important history paintings are lost, notably The Plague in Rome of 1884. One of his last large-scale canvases was the huge polyptych Sic Transit..., a vast allegory of the fall of the Roman Empire and the rise of the Christian era, completed in 1912 and exhibited in Vienna the following year. During the First World War, Hirémy-Hirschl worked as a war correspondent for Austria, making drawings of the naval bases at Trieste and elsewhere. He continued to live and work in Rome until his death, devoting much of his time to smaller paintings, seascapes and nature studies. He also produced a number of book illustrations, designs for frontispieces, and other graphic work, as well as several etchings and a handful of sculptures.

Provenance

The artist’s studio, Rome, and by descent to his daughter Maud

Thence by descent to a private collection

Galleria Carlo Virgilio, Rome

Private collection, London.

Thence by descent to a private collection

Galleria Carlo Virgilio, Rome

Private collection, London.