Giovanni Domenico TIEPOLO

(Venice 1727 - Venice 1804)

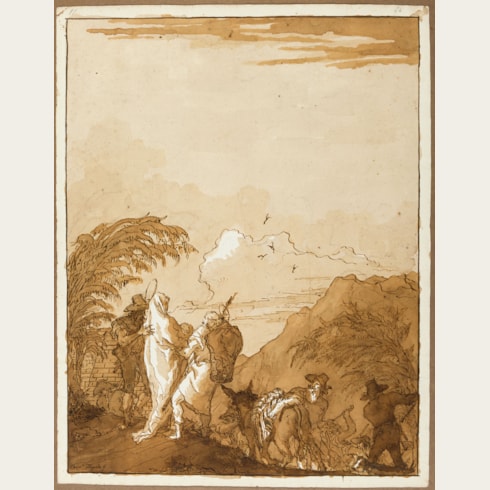

A Reclining Centaur and a Satyress in a Landscape

Signed Dom.o Tiepolo f. at the lower right and numbered 9 at the upper left.

Inscribed Gli amori de’ centauri colle ninfe boschereccie - disegno originale / di Domenico Tiepolo col nome autografo – fr. 5. on the verso.

Numbered 294 on the verso.

194 x 269 mm. (7 5/8 x 10 5/8 in.)

Among other drawings of a languid centaur with an acquiescent nymph or satyress are examples in the British Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, as well as several in private collections, while the subject is also found in a large drawing of The Lady and the Centaur in the Cleveland Museum of Art, one of the artist’s late Punchinello cycle of finished drawings. A similar arrangement of an amorous centaur and satyress also appears, albeit in reverse, in one of the frescoes painted by Domenico for the Tiepolo villa at Zianigo, now in the Ca’ Rezzonico in Venice.

In his seminal article on this fascinating group of drawings, Jean Cailleux praised ‘the inexhaustible inventiveness,...the freedom and unerringness of touch,...the fluidity of Domenico Tiepolo’s use of wash in this series which never becomes monotonous.’ Unlike most of the artist’s other series of independent pen and wash drawings, such as the ‘Large Biblical Series’ or the Punchinello drawings, there is no obvious narrative thread that ties these scenes together, though they are nevertheless linked by being of similar size and technique, and containing the same cast of mythological characters; centaurs, satyrs, nymphs and fauns. As James Byam Shaw has noted, ‘The drawings of this series are perhaps the most charming and original of all Domenico’s drawings – original because less dependent on the inventions of other artists than some of his other series...and catching exactly the charm and gaiety of the pagan mythology.’

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo is assumed to have begun his career in the family studio by copying his father’s drawings, although he also created his own drawings as designs for etchings, a practice which occupied much of his time in the 1740s and 1750s. His first independent drawings for paintings are those related to a series of fourteen paintings of the Stations of the Cross for the Venetian church of San Polo, completed when he was just twenty. Between 1750 and 1770, Domenico worked closely with his father as an assistant, notably in Würzburg, at the Villa Valmarana in Vicenza and the Villa Pisani at Strà, and in Madrid. From the late 1740s he also began to be entrusted with his own independent commissions, and the drawings for these display a manner somewhat different from that of his father, with a particular interest in lighthearted genre motifs.

Soon after Giambattista Tiepolo’s sudden death in Madrid in 1770, Domenico returned to his native Venice, where he enjoyed much success as a decorative painter. He continued to expound the grand manner of history painting established by his father - the ‘Tiepolo style’, as it were – and by 1780 his reputation was such that he was named president of the Accademia di Belle Arti in Venice. Within a few years, however, he seems to have largely abandoned painting. In his sixties and living effectively in retirement at the Tiepolo family villa at Zianigo, on the Venetian mainland, he produced a large number of pen and wash drawings that are a testament to his inexhaustible gift for compositional invention.

For much of the last twenty years of his career, Domenico Tiepolo seems to have painted only occasionally, and instead worked primarily as a draughtsman, producing a large number of pen and wash drawings that may collectively be regarded as perhaps his finest artistic legacy. These drawings were, for the most part, executed as a series of several dozen or more themed drawings, many of which were numbered. Among these are several series of drawings of religious and mythological subjects, as well as a varied group of genre scenes, numbering around a hundred sheets, generally referred to as the so-called ‘Scenes of Contemporary Life’, and a celebrated series of 104 drawings entitled the Divertimenti per li regazzi, illustrating scenes from the life of Punchinello, a popular character from the Commedia dell’Arte.

Domenico’s highly finished late drawings, almost all of which were signed, were undoubtedly intended as fully realized, autonomous works of art. While it is certainly possible that they were produced as works of art to be offered for sale to collectors, almost none of the drawings appear to have been dispersed in Domenico’s lifetime. The fact, too, that many of the drawings are numbered, possibly by the artist himself, and that most remained together in groups for many years after his death, would also suggest that they were retained in his studio throughout his life, as indeed he also kept numerous albums of drawings by his father. It is most likely, therefore, that these late drawings by Domenico were done simply for his own pleasure. Nevertheless, they have consistently enjoyed immense popularity since the artist’s death, and continue to entice collectors today. As Catherine Whistler has noted, ‘Domenico’s spirited and inventive independent sheets have long been appreciated, particularly by French and American collectors of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; his quirky sense of humor, acutely observant eye, and zestful approach to his subjects lend his drawings a peculiarly modern appeal.’

As Michael Levey has also noted of the artist, ‘Domenico Tiepolo’s drawings provide us with the more private side of him, but they also serve to represent his career at all stages. He drew continually: sometimes very closely in the manner of his father; at the opposite remove, in the late Punchinello drawings for example, his manner and matter could never be mistaken for anyone else’s...The key to Domenico is in drawings: he began as a draughtsman and, one is tempted to say, all his paintings betray the draughtsman.’

Provenance

Literature