David HOCKNEY

(Bradford Born 1937)

Dettifoss from the Other Side

Sold

Watercolour on four sheets of paper.

Signed and dated D.H. ’02 at the lower left.

915 x 1216 mm. (36 x 47 7/8 in.) overall dimensions

Signed and dated D.H. ’02 at the lower left.

915 x 1216 mm. (36 x 47 7/8 in.) overall dimensions

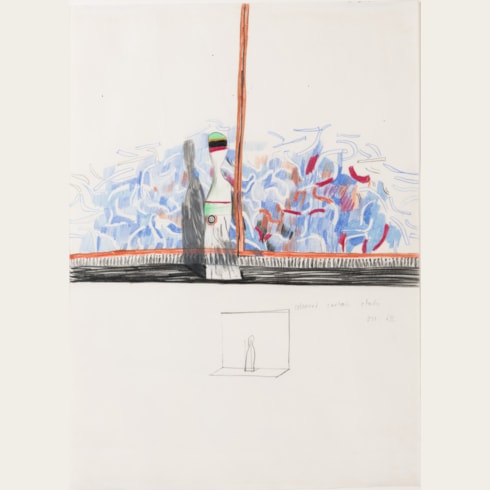

David Hockney came to watercolour relatively late in his career. As he has recently said, ‘It’s not an easy medium but I like the discipline it gives you. Once you put down the marks, that’s it. You know you can’t fudge it. There are certain ways you have to work. You can’t put a light colour on a dark colour…one watercolour technique you use is with transparent colours and the white of the paper. How many layers you put on depends on how much glow there’ll be. If there are too many layers, the image will become dull.’

In March 2002 Hockney made several visits to the exhibition American Sublime at Tate Britain in London. The exhibition, devoted to the 19th century tradition of epic landscape painting in America, made a particular impression on the artist. As he recalled later that year, ‘The subject matter of American Sublime – the large landscape – made me, in April 2002, think of going North. I know sunsets don’t last long in the South West. To have longer periods of twilight (when colour is not bleached but extremely rich) one has to go North. I made a trip to Norway in May, was very taken with the dramatic landscape and returned to go much further north, when in June the sun never sets at all. You can see the landscape at all hours, 24 hours a day. There is no night. I found myself deeply attracted to it, and then went to Iceland twice to tour the island.’

These trips to Scandinavia and Iceland, close to the Arctic Circle, resulted in a series of large-scale, panoramic watercolours, drawn on several sheets of paper of equal size. These large watercolour drawings, made up of several joined sheets of paper, were in turn based on a series of double-page drawings in small sketchbooks, which remain in the artist’s collection. Hockney has noted of these monumental works that ‘overcoming the technical difficulties of the watercolour medium for large scale works was a solvable problem. The main difficulty is that washes have to be put on horizontally, but drawing really has to be done vertically to enable one to see it. As all this developed it opened out the medium, leading eventually to the large double portraits…’

The present sheet depicts the waterfall of Dettifoss in Iceland, one of the largest and most powerful waterfalls in Europe. There the river Jökulsá á Fjöllum, one hundred metres wide, plunges over a basaltic cliff some forty-five metres in height into a deep gorge in the Jökulsárgljúfur canyon. Access to the waterfall is difficult, and the site can only be reached by a rough road.

In March 2002 Hockney made several visits to the exhibition American Sublime at Tate Britain in London. The exhibition, devoted to the 19th century tradition of epic landscape painting in America, made a particular impression on the artist. As he recalled later that year, ‘The subject matter of American Sublime – the large landscape – made me, in April 2002, think of going North. I know sunsets don’t last long in the South West. To have longer periods of twilight (when colour is not bleached but extremely rich) one has to go North. I made a trip to Norway in May, was very taken with the dramatic landscape and returned to go much further north, when in June the sun never sets at all. You can see the landscape at all hours, 24 hours a day. There is no night. I found myself deeply attracted to it, and then went to Iceland twice to tour the island.’

These trips to Scandinavia and Iceland, close to the Arctic Circle, resulted in a series of large-scale, panoramic watercolours, drawn on several sheets of paper of equal size. These large watercolour drawings, made up of several joined sheets of paper, were in turn based on a series of double-page drawings in small sketchbooks, which remain in the artist’s collection. Hockney has noted of these monumental works that ‘overcoming the technical difficulties of the watercolour medium for large scale works was a solvable problem. The main difficulty is that washes have to be put on horizontally, but drawing really has to be done vertically to enable one to see it. As all this developed it opened out the medium, leading eventually to the large double portraits…’

The present sheet depicts the waterfall of Dettifoss in Iceland, one of the largest and most powerful waterfalls in Europe. There the river Jökulsá á Fjöllum, one hundred metres wide, plunges over a basaltic cliff some forty-five metres in height into a deep gorge in the Jökulsárgljúfur canyon. Access to the waterfall is difficult, and the site can only be reached by a rough road.

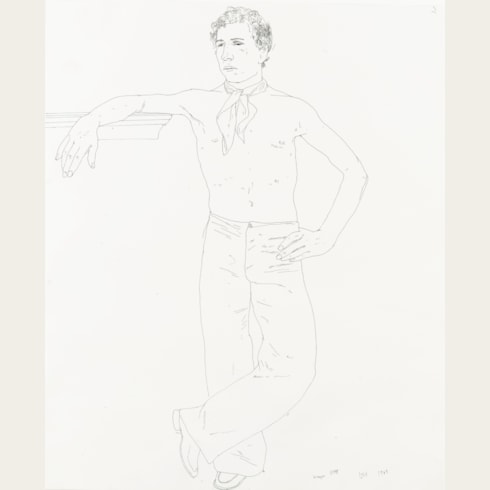

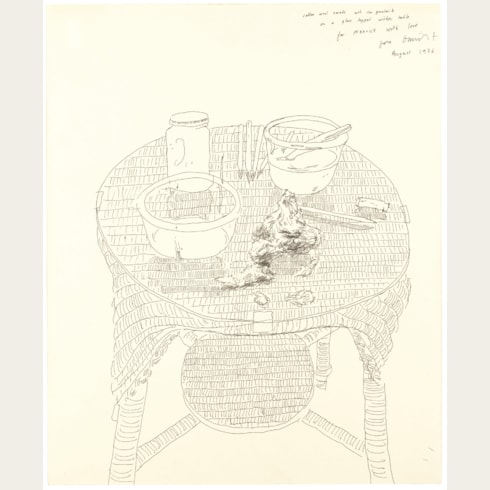

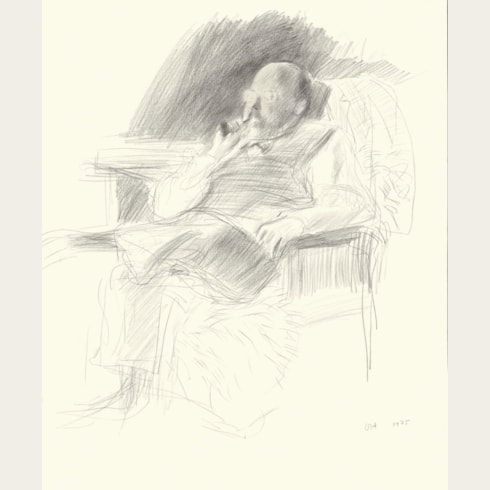

Although David Hockney made his first portraits and self-portraits as a teenager, it was not until the mid-1960’s that he began to seriously apply himself to portraiture, inspired by a new relationship with a young lover, Peter Schlesinger. Since that time, he has continued to produce portraits in the form of paintings, drawings, prints and photographs throughout his long and successful career. Portraiture has, indeed, been a central theme in much of his work. His sitters, with few exceptions, have been made up of friends, family, and lovers; people whom he knew well, and with whom he felt comfortable. As he himself has noted, ‘Naturally I’ve always liked drawing people, so one tends to draw one’s friends and the people one knows around you – anybody does…I think the way I draw, the more I know and react to people, the more interesting the drawings will be. I don’t really like struggling for a likeness. It seems a bit of a waste of effort, in a sense, just doing that. And you’d never know, anyway. If you don’t know the person, you don’t really know if you’ve got a likeness at all. You can’t really see everything in the face. I think it takes quite a lot of time.’ As a recent scholar has written, ‘the intensity of drawing meant that Hockney tended only to make portraits of friends who were sufficiently patient and understanding, and with whom he was sufficiently familiar to be able to capture the changes and variation in their appearance.’

Hockney’s portraits have been executed in almost every medium in which he has worked, including oil paint and acrylic, pencil, pen and ink, charcoal, coloured crayons, pastel and, more recently, watercolour, as well as in the form of etchings, lithographs, Polaroid photographs and photographic collages. Whatever the medium or technique, however, Hockney’s portraiture is invariably characterized by the artist’s close observation of his subject. As Marco Livingstone has noted, ‘All of the artist’s portrait drawings were made in the presence of the sitter, for in Hockney’s view a portrait by definition has to be done from life or very soon after. This, however, by no means excludes the possibility of incorporating elements from memory, since previous knowledge of how someone behaves or looks can alter one’s apprehension of that person on a later occasion. Hockney is convinced that having recourse to information gathered from past experience, in conjunction with the evidence of the moment, has allowed him to make livelier and more animated faces than might otherwise have been possible.’

Provenance

L. A. Louver Gallery, Los Angeles.