Lucian FREUD

(Berlin 1922 - London 2011)

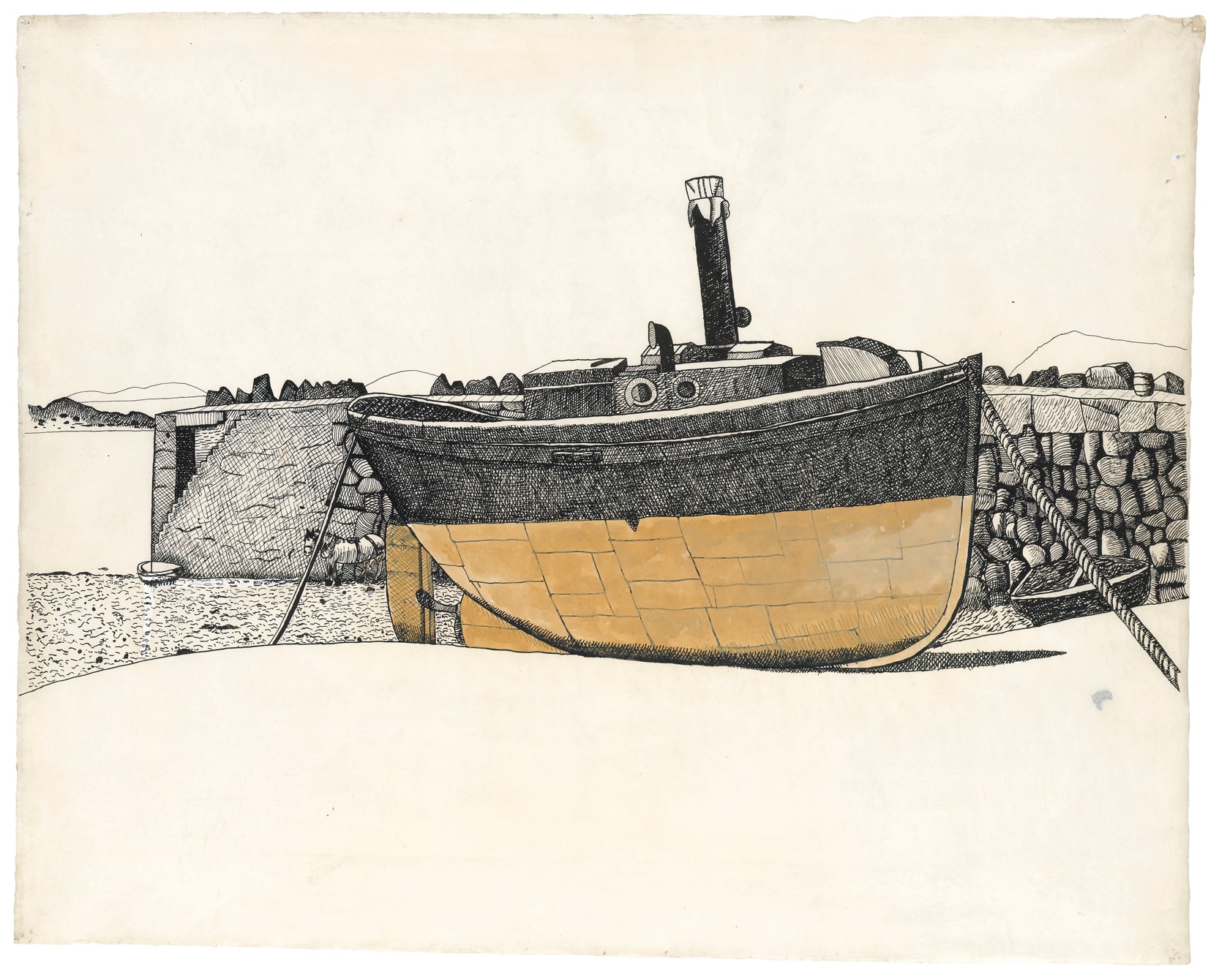

Boat, Connemara

Sold

Pen and black ink and tempera, with touches of white heightening, on thin Whatman paper.

445 x 562 mm. (17 1/2 x 22 1/8 in.)

445 x 562 mm. (17 1/2 x 22 1/8 in.)

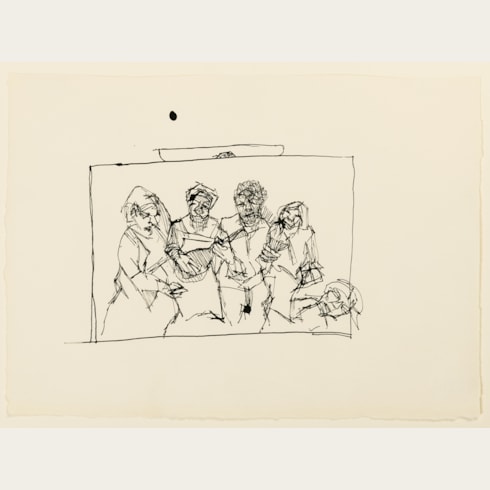

One of Lucian Freud’s finest drawings, this superb and unusually large sheet is a major addition to his oeuvre. Purchased from the artist soon after it was made, the drawing remained in the same private collection for over sixty years, and until recently was completely unknown to scholars. With its masterly technique of pen and ink and tempera, this impressive sheet is a testament to Freud’s powers of observation, and his remarkable skill as a draughtsman.

The early years of Freud’s career were largely devoted to drawing, and the practice would remain a vital part of the artist’s development throughout the 1940s and early 1950s. At his first solo exhibition at the Lefevre Gallery in the winter of 1944, as well as in a second show in early 1946, a number of drawings were shown. As Freud himself recalled, many years later, ‘I would have thought I did 200 drawings to every painting in those early days. I very much prided myself on my drawing. My work was in a sense very linear.’ This was a period of sustained activity in drawing, with Freud creating an important series of self-contained works in charcoal, ink, watercolour, coloured crayons, pencil and chalk. As William Feaver has noted, ‘By the mid-1940’s, Freud’s drawings had an extraordinary allure. In charcoal, conté and chalk on Ingres paper he caught every texture from bamboo to corduroy...’ Another scholar has written of Freud’s early drawings that ‘One is struck not just by evidence of close observation but by a certain stylised, self-preening stance towards the subject – one not immune to the appeal of pattern and repetition, yet adhering strictly to the literal over the abstract. The two modes – patterning and description – are not in opposition; rather, they are made to enhance one another...these new, more precise modes of rendering were all part of an attempt by Freud to endow his subjects with a heightened presence. It became possible in this new register to make inanimate, utterly still things vibrate with immediacy.’

From the middle of the 1940s onwards, Freud’s drawings began to display a greater confidence in his powers of observation and expression, and his draughtsmanship reaches new heights of refinement. At this time, the artist’s drawings - whether in pen, pencil or crayon - began to display techniques associated with printmaking, like hatching, stippling and dotting, and it is perhaps not surprising that it was around this time that he began to experiment with etching. However, by the middle of the 1950s Freud had begun to abandon drawing altogether, fearing that the predominantly linear, graphic quality of his paintings was impeding his brushwork. (As he stated, ‘people thought and said and wrote that I was a very good draughtsman but my paintings were linear and defined by my drawing. [They said] you could tell what a good draughtsman I was from my painting…I thought if that’s at all true I must stop.’) After the mid-1950s Freud produced drawings relatively infrequently, and certainly without the sustained productivity of the 1940s and early 1950s. The medium of etching, in many respects, took the place of drawing as his preferred graphic medium.

The present sheet had been thought to date from a period of three weeks that Freud spent in Ireland in August 1948, not long after his marriage to Kitty Garman and the birth of their daughter Annie. Together with his then lover, the young English painter Anne Dunn (b.1929), Freud stayed at the Zetland Arms hotel overlooking Cashel Bay in Connemara, in County Galway on the west coast of Ireland. It has long been assumed that the only work Freud produced during this trip is the pastel drawing Interior Scene, which depicts Dunn half hidden behind a curtain, standing by a window in a room at the Zetland Arms.

This drawing, however, instead dates from a second visit that Freud made to Connemara a few years later, in 1951. Anne Dunn recalls the present drawing as having been executed in the summer of 1951, when she and her husband Michael Wishart returned to Connemara, along with Freud and Kitty, with the two couples staying in a pair of rented cottages.

Observed with Freud’s keen, analytical eye for a composition, this sizeable drawing depicts a small steamboat drawn up at low tide on the beach near the Zetland Arms, on an inlet in Cashel Bay. Behind the boat, which was used to ferry travellers across the bay, is the low stone pier, built around 1860 and still standing, with Cashel Hill behind. (The spot on which the artist stood to make the drawing was just below and about a hundred metres west of the Zetland Arms, with his back to the hotel. Just to his right, unseen in the drawing, is the R342 road, which follows the shore of Cashel Bay.) In the left background can be seen a Connemara pony - a breed originating in County Galway, where the harsh landscape resulted in a hardy, tough breed of horse - which would have been used to haul loads of seaweed and kelp from the bay, while a small rowboat is visible in the right background.

This large and imposing drawing is a tour de force of Freud’s masterful penwork, with the stones of the pier, the water, and the boat and its ropes drawn with a precise technique of hatched and cross-hatched pen lines. The lower hull of the boat – the only part of the drawing with any colour - is drawn in an ochre tone using tempera, to represent the copper hull sheathing of the boat. Compositionally, Freud has chosen to leave the foreground and the sky blank, with the upper and lower part of the paper untouched, allowing the subject of the drawing to be concentrated in the precise centre of the sheet.

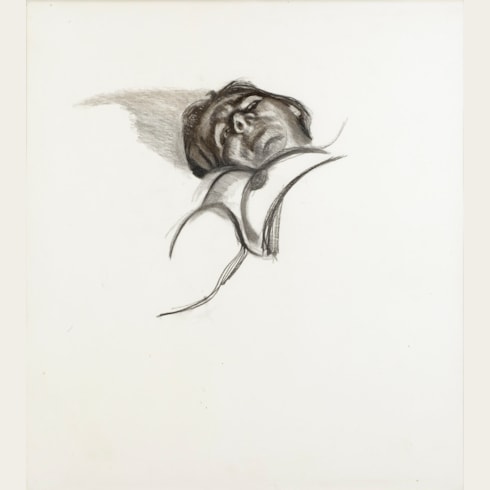

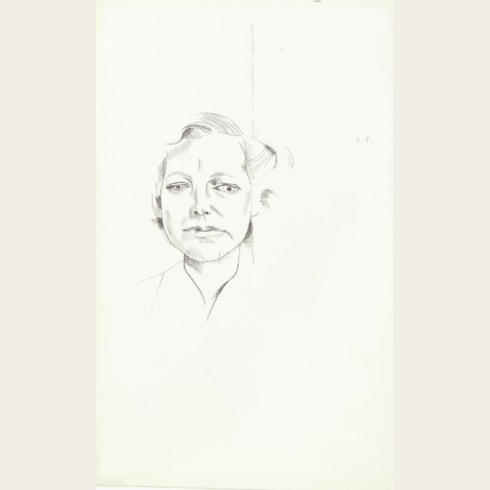

In its use of a fine calligraphic pen line applied with a combination of stippling, dotting, hatching and crosshatching in the manner of an etching, the present sheet may be likened to drawings of the late 1940s or early 1950s such as Man at Night (Self-Portrait), a large drawing of 1947-1948, or in such smaller-scale pen drawings as one of the artist’s young neighbour Charlie Lumley as Narcissus, a drawing of 1948-1949 in the Tate, or a drawing of Herculesof 1949. The same precision is also found in a number of pencil and crayon drawings of this date intended as illustrations for William Samson’s book The Equilibriad, published in 1948.

Soon after it was drawn, the present sheet was acquired directly from the artist by the architect and collector William Gough Howell (1922-1974). Having served in the Royal Air Force during the Second World War, in the course of which he was awarded the DFC in 1943, Howell returned to civilian life and became a student of architecture at Cambridge. There he founded the Cambridge Contemporary Art Trust, a picture-loan scheme open to any student or resident of Cambridge. Howell built an impressive collection for the Trust, buying works of art directly from artist’s studios, as well as gaining the patronage of such prominent figures as Henry Moore, Kenneth Clark and Herbert Read. In 1948 Howell organized the first exhibition of the Cambridge Contemporary Art Trust, which included some works by Freud, as well as John Craxton and other artists. Howell acquired the present sheet for his own collection, possibly around 1954, when the artist and his second wife, Lady Caroline Blackwood, moved into a flat in Soho that had been previously occupied by Howell. The drawing remained in the possession of Howell’s descendants until 2012.

The early years of Freud’s career were largely devoted to drawing, and the practice would remain a vital part of the artist’s development throughout the 1940s and early 1950s. At his first solo exhibition at the Lefevre Gallery in the winter of 1944, as well as in a second show in early 1946, a number of drawings were shown. As Freud himself recalled, many years later, ‘I would have thought I did 200 drawings to every painting in those early days. I very much prided myself on my drawing. My work was in a sense very linear.’ This was a period of sustained activity in drawing, with Freud creating an important series of self-contained works in charcoal, ink, watercolour, coloured crayons, pencil and chalk. As William Feaver has noted, ‘By the mid-1940’s, Freud’s drawings had an extraordinary allure. In charcoal, conté and chalk on Ingres paper he caught every texture from bamboo to corduroy...’ Another scholar has written of Freud’s early drawings that ‘One is struck not just by evidence of close observation but by a certain stylised, self-preening stance towards the subject – one not immune to the appeal of pattern and repetition, yet adhering strictly to the literal over the abstract. The two modes – patterning and description – are not in opposition; rather, they are made to enhance one another...these new, more precise modes of rendering were all part of an attempt by Freud to endow his subjects with a heightened presence. It became possible in this new register to make inanimate, utterly still things vibrate with immediacy.’

From the middle of the 1940s onwards, Freud’s drawings began to display a greater confidence in his powers of observation and expression, and his draughtsmanship reaches new heights of refinement. At this time, the artist’s drawings - whether in pen, pencil or crayon - began to display techniques associated with printmaking, like hatching, stippling and dotting, and it is perhaps not surprising that it was around this time that he began to experiment with etching. However, by the middle of the 1950s Freud had begun to abandon drawing altogether, fearing that the predominantly linear, graphic quality of his paintings was impeding his brushwork. (As he stated, ‘people thought and said and wrote that I was a very good draughtsman but my paintings were linear and defined by my drawing. [They said] you could tell what a good draughtsman I was from my painting…I thought if that’s at all true I must stop.’) After the mid-1950s Freud produced drawings relatively infrequently, and certainly without the sustained productivity of the 1940s and early 1950s. The medium of etching, in many respects, took the place of drawing as his preferred graphic medium.

The present sheet had been thought to date from a period of three weeks that Freud spent in Ireland in August 1948, not long after his marriage to Kitty Garman and the birth of their daughter Annie. Together with his then lover, the young English painter Anne Dunn (b.1929), Freud stayed at the Zetland Arms hotel overlooking Cashel Bay in Connemara, in County Galway on the west coast of Ireland. It has long been assumed that the only work Freud produced during this trip is the pastel drawing Interior Scene, which depicts Dunn half hidden behind a curtain, standing by a window in a room at the Zetland Arms.

This drawing, however, instead dates from a second visit that Freud made to Connemara a few years later, in 1951. Anne Dunn recalls the present drawing as having been executed in the summer of 1951, when she and her husband Michael Wishart returned to Connemara, along with Freud and Kitty, with the two couples staying in a pair of rented cottages.

Observed with Freud’s keen, analytical eye for a composition, this sizeable drawing depicts a small steamboat drawn up at low tide on the beach near the Zetland Arms, on an inlet in Cashel Bay. Behind the boat, which was used to ferry travellers across the bay, is the low stone pier, built around 1860 and still standing, with Cashel Hill behind. (The spot on which the artist stood to make the drawing was just below and about a hundred metres west of the Zetland Arms, with his back to the hotel. Just to his right, unseen in the drawing, is the R342 road, which follows the shore of Cashel Bay.) In the left background can be seen a Connemara pony - a breed originating in County Galway, where the harsh landscape resulted in a hardy, tough breed of horse - which would have been used to haul loads of seaweed and kelp from the bay, while a small rowboat is visible in the right background.

This large and imposing drawing is a tour de force of Freud’s masterful penwork, with the stones of the pier, the water, and the boat and its ropes drawn with a precise technique of hatched and cross-hatched pen lines. The lower hull of the boat – the only part of the drawing with any colour - is drawn in an ochre tone using tempera, to represent the copper hull sheathing of the boat. Compositionally, Freud has chosen to leave the foreground and the sky blank, with the upper and lower part of the paper untouched, allowing the subject of the drawing to be concentrated in the precise centre of the sheet.

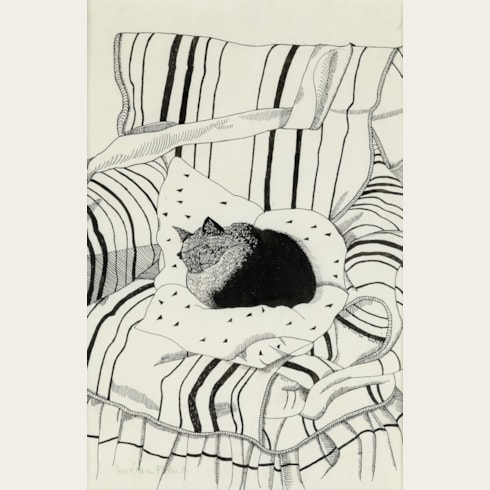

In its use of a fine calligraphic pen line applied with a combination of stippling, dotting, hatching and crosshatching in the manner of an etching, the present sheet may be likened to drawings of the late 1940s or early 1950s such as Man at Night (Self-Portrait), a large drawing of 1947-1948, or in such smaller-scale pen drawings as one of the artist’s young neighbour Charlie Lumley as Narcissus, a drawing of 1948-1949 in the Tate, or a drawing of Herculesof 1949. The same precision is also found in a number of pencil and crayon drawings of this date intended as illustrations for William Samson’s book The Equilibriad, published in 1948.

Soon after it was drawn, the present sheet was acquired directly from the artist by the architect and collector William Gough Howell (1922-1974). Having served in the Royal Air Force during the Second World War, in the course of which he was awarded the DFC in 1943, Howell returned to civilian life and became a student of architecture at Cambridge. There he founded the Cambridge Contemporary Art Trust, a picture-loan scheme open to any student or resident of Cambridge. Howell built an impressive collection for the Trust, buying works of art directly from artist’s studios, as well as gaining the patronage of such prominent figures as Henry Moore, Kenneth Clark and Herbert Read. In 1948 Howell organized the first exhibition of the Cambridge Contemporary Art Trust, which included some works by Freud, as well as John Craxton and other artists. Howell acquired the present sheet for his own collection, possibly around 1954, when the artist and his second wife, Lady Caroline Blackwood, moved into a flat in Soho that had been previously occupied by Howell. The drawing remained in the possession of Howell’s descendants until 2012.

The early years of Lucian Freud’s career were largely devoted to drawing, and the practice would remain a vital part of the artist’s development throughout the 1940’s and early 1950’s. As Freud himself recalled, many years later, ‘I would have thought I did 200 drawings to every painting in those early days. I very much prided myself on my drawing. My work was in a sense very linear.’ The 1940’s in particular were a period of sustained activity in drawing, with the artist creating an important series of self-contained works in charcoal, ink, watercolour, coloured crayons, pencil and chalk. As Lawrence Gowing has noted, ‘Freud’s drawings in 1943 and 1944 have already a quality of resolved classical line, with the minimum of inflexions to make legible its formal message, which is otherwise the property of only the very best painters of twenty years before...Style and capacity developed rapidly in these drawings...’ William Feaver further comments that ‘By the mid-1940’s, Freud’s drawings had an extraordinary allure. In charcoal, conté and chalk on Ingres paper he caught every texture from bamboo to corduroy...’

Freud had his first solo exhibition at the Lefevre Gallery in London in the winter of 1944, followed by a second show in early 1946, and in both exhibitions a number of drawings were shown. Writing of the artist’s drawings of this period, Robert Hughes noted of Freud that ‘there is no doubt that part of his reputation as a boy prodigy in London art circles in the war years rested on his single-minded commitment to linear description rather than painterly evocation…The precocity of the early work, some of which...reveals a degree of control extraordinary in an artist of 21, lies in the fierce independence of its delineation.’ However, by the middle of the 1950’s the artist had abandoned drawing altogether, fearing that the predominantly linear, graphic quality of his paintings was impeding his brushwork. Since then he produced drawings relatively infrequently, and certainly without the sustained productivity of the 1940’s and early 1950’s. The medium of etching, in many respects, took the place of drawing as his preferred graphic medium.

Provenance

Acquired from the artist by William G. Howell, Cambridge and London, probably in the early 1950s

Thence by descent.

Thence by descent.

Literature

Phoebe Hoban, Lucian Freud: Eyes Wide Open, Boston and New York, 2014, pp.41-42; Paris, Société du Salon du dessin, 25e Anniversaire du Salon du Dessin 1991-2016, 2016, illustrated p.237; James Finch, ‘Circa 1950; Lucian Freud at the Hanover Gallery’, in Christina Kennedy and Nathan O’Donnell, ed., Life Above Everything: Lucian Freud and Jack B. Yeats, exhibition catalogue, 2019, pp.102-103, illustrated p.99; Aidan Dunne, ‘Lucian Freud and Jack B. Yeats: A couple of outsiders side by side’, The Irish Times, 3 July 2019; Tom Walker, ‘An unlikely couple? Lucian Freud and Jack B. Yeats, reviewed’, Apollo-Magazine.com, 6 August 2019.

Exhibition

Dublin, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Life Above Everything: Lucian Freud and Jack B. Yeats, 2019-2020.