Lucian FREUD

(Berlin 1922 - London 2011)

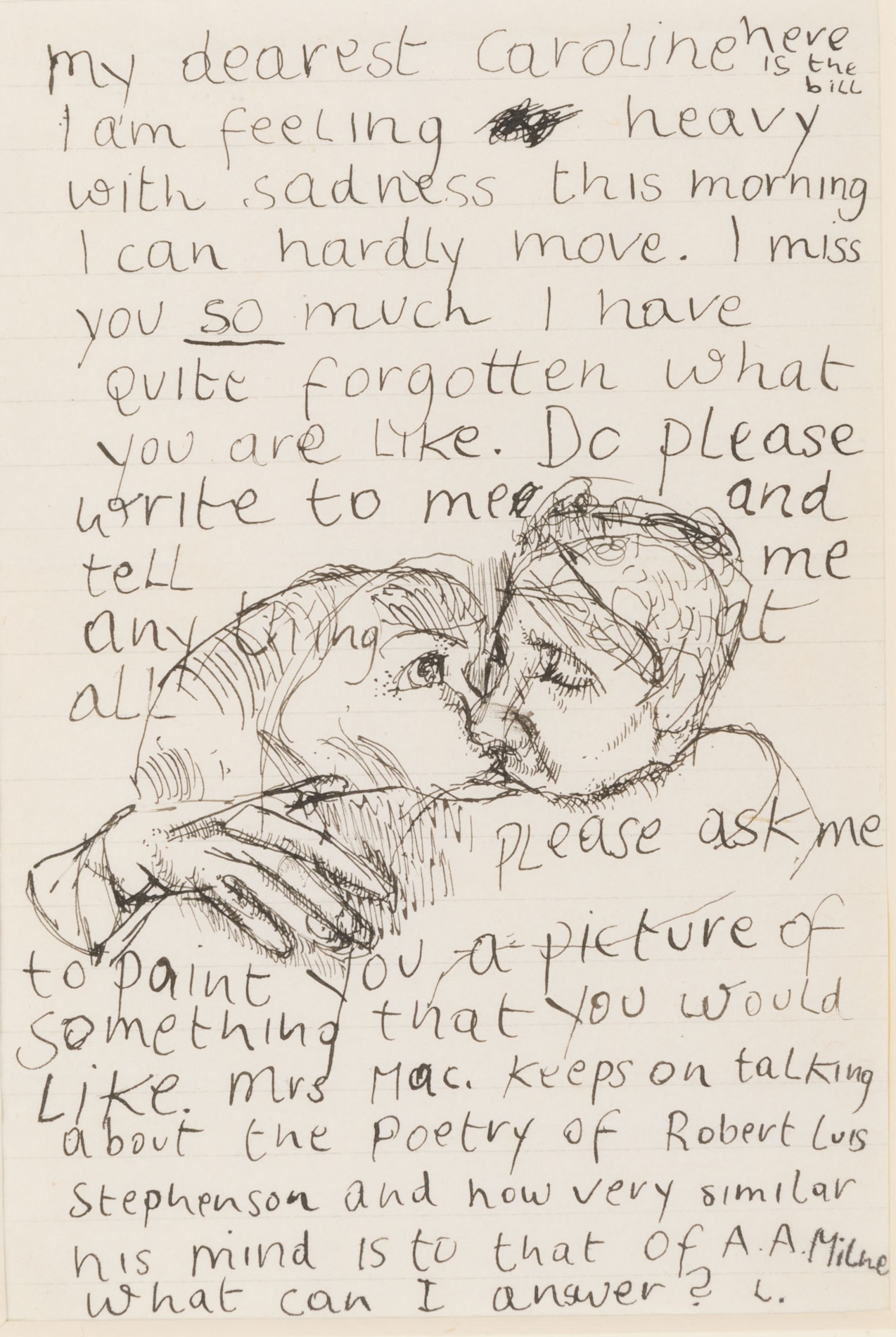

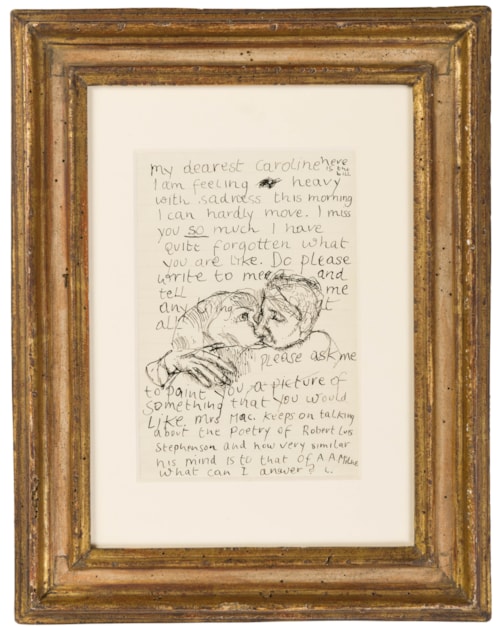

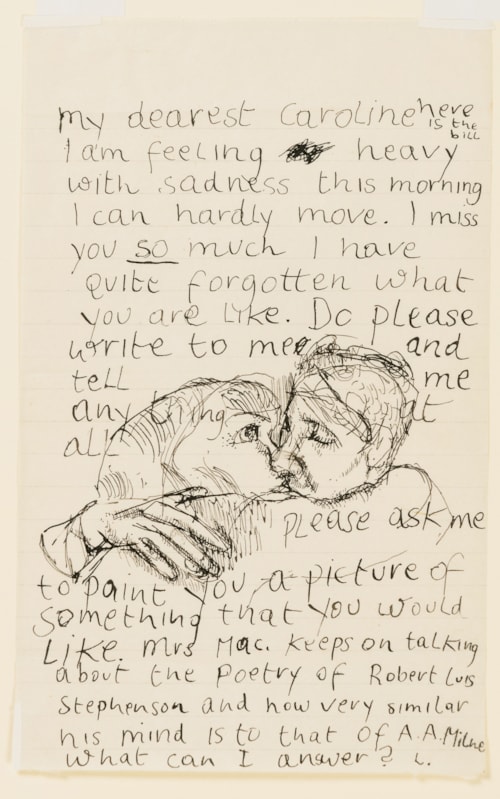

An Illustrated Letter from the Artist to Caroline Blackwood

Sold

Pen and black ink.

202 x 127 mm. (8 x 5 in.)

202 x 127 mm. (8 x 5 in.)

The letter reads:

My dearest Caroline [here is the bill]

I am feeling heavy

with sadness this morning

I can hardly move. I miss

you so much I have

quite forgotten what

you are like. Do please

write to mee and

tell me

anything at

all

Please ask me

to paint you a picture of

something that you would

like. Mrs Mac. keeps on talking

about the poetry of Robert Luis

Stephenson and how very similar

his mind is to that of A.A. Milne.

What can I answer? L.

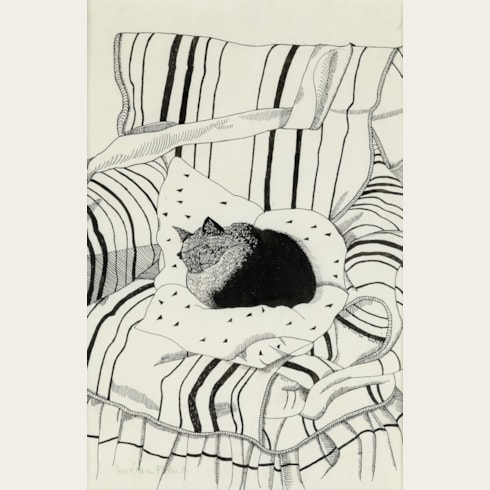

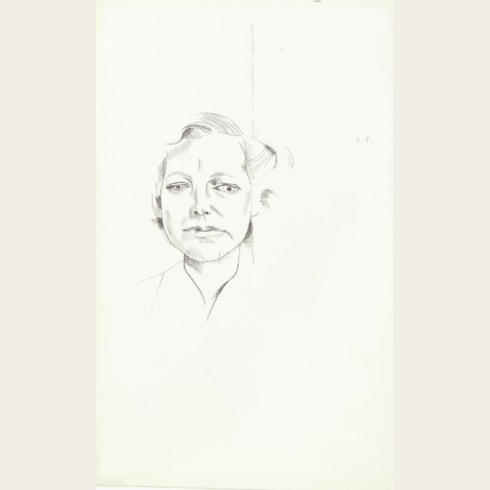

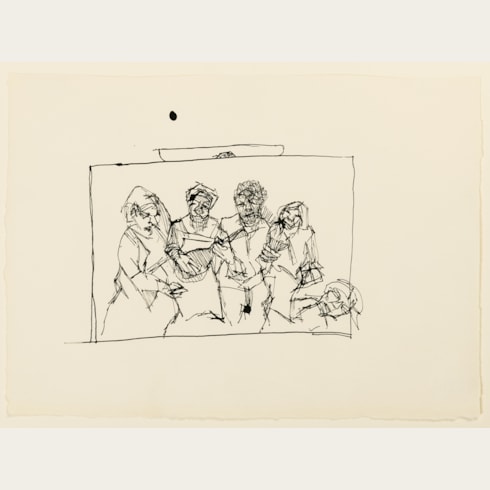

Datable to the spring or summer of 1952, this is the only known extant letter from Lucian Freud to his lover and future wife, Lady Caroline Blackwood, and was written at the height of his obsession with her. It is especially compelling since the text of the letter surrounds a pen portrait that the artist drew of himself in an embrace with his lover. The portrait of Caroline in this letter captures her unmistakable features; her large, startled eyes and blonde, sweeping hairstyle. Three of Freud’s most compelling painted portraits of Caroline Blackwood, all today in private collections, were executed in 1952, at around the same time as this letter; Girl in Bed and Girl with a Starfish Necklace, as well as a small oil on copper entitled Girl Reading. As has been noted, ‘Lucian Freud’s paintings of Caroline are among the most tender and lyrical portraits he has ever executed.’

Lady Caroline Maureen Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood (1931-1996) first briefly met Freud in 1949 at a party given by the socialite Ann Rothermere. The wife of the press magnate Lord Rothermere, Ann (who would go on to marry her lover, the novelist Ian Fleming, in 1952), was famous for her parties at her homes at Warwick House, near Green Park in London, and at White Cliffs, on St. Margaret’s Bay in Kent, and it was at one of these parties that Freud and Blackwood met again in late 1951. As the artist later recalled, in conversation with Geordie Greig, ‘[Ann Rothermere] asked me to one of those marvellous parties, semi-royal, quite a lot of them were there, and she said, “I hope you find someone you’d like to dance with”, and that sort of thing. And suddenly there was this one person and that was Caroline…She was just exciting in every way and was someone who had taken absolutely no trouble with herself…I went up to her and I danced and danced and I danced and danced...I don’t really think of myself in a dramatic romantic way. I just thought of what I wanted to do, you know, take her home alone, that sort of thing. That night I went home and started painting her.’ In an interview published in 1995, when she was sixty-three, Caroline Blackwood recalled that ‘“Lucian was fantastic, very brilliant, incredibly beautiful, though not in a movie-star way…I remember he was very mannered, he wore these long side whiskers, which nobody else had then. And he wore funny trousers, deliberately. He wanted to stand out in a crowd, and he did.”’

Freud promptly fell deeply in love. Despite the fact that he was married to Kitty Garman and the father of a new baby girl, he pursued Caroline with a passion that bordered on obsession. As Grieg has noted, ‘Ignoring what everyone else thought, as he nearly always did, he was utterly bewitched by Caroline…Lucian adored Caroline’s careless abandon which merged into self-centredness. As an artist, he understood selfishness. In some ways, with Caroline he had met his match.’ As Blackwood’s biographer has written, ‘At eighteen Caroline was fair-haired, dishevelled, slender, athletic, intense, puckish, and shy. She no doubt satisfied Lucian’s aesthetic sense, but she also possessed intelligence and courage. And, perhaps equally important, she was an aristocrat and a Guinness heiress.’

Despite the severe disapproval of her mother, the Dowager Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava, Caroline eloped with Freud to Paris in 1952. Something of the intensity of the couple’s relationship in captured in a letter from the writer and biographer James Pope-Hennessy to his friend Nolwen de Janzé, written from London at the end of September 1953: ‘Lucian and Caroline turned up here unexpectedly this morning, had baths and breakfast and wandered away again…They were sweet, but like somnambulists and wrapped in that impenetrable unawareness of people in love – do you know what I mean? - entirely unaware of the outside world, and rather expecting everybody else to do things for them. People in love are rather like royalty, I think. I can’t see any sense whatever in their marrying; but this, in Paris, they propose to do.’ Freud and Blackwood were married in London a few weeks later, on December 9th, 1953, a day after the artist’s thirty-first birthday.

By 1956, however, the marriage was in difficulties, with Caroline increasingly unhappy. That year she had left him and fled to Rome, eventually filing for divorce in 1957. By most accounts, Freud was devastated by Caroline’s decision to abandon the marriage, and was left deeply unhappy. (Both the artist Michael Andrews and the art critic David Sylvester later recalled that this was the only time they had ever seen Freud weeping.) As the artist’s biographer has noted, ‘Freud felt injured as well as distraught. Not so much because it was she who had left but because, ultimately, she had gone even further than he in nullifying the marriage. “Things could have been better for her with different behaviour on my part...”’ The writer and diarist Joan Wyndham, who had had a brief affair with Freud in 1945, later opined that ‘Caroline was the great love of Lucian’s life…With Caroline he behaved terribly well. Very unusual. He didn’t love any of us, really…he must have known that she loved him, which was a great thing.’ This period also seems to have led to a change in the way the artist depicted women in his paintings, with much less of the tenderness found in the earlier portraits. As Caroline herself noted, ‘Lucian’s painting changed violently after I left him…Lucian painted me in a different way to how he’s painting other people. There’s much more lyricism in these early works.’

Following the divorce, Caroline – who never seems to have spoken badly of Freud throughout the rest of her life – became a gifted writer, and in later years was married to two equally brilliant men; the composer Israel Citkowitz and the poet Robert Lowell. In January 1996, when she had been diagnosed with an inoperable cancer and had checked into the Mayfair Hotel in New York to spend her final weeks, Freud phoned her from London and they had a long conversation. Caroline’s daughter Ivana Lowell, listening to her mother speaking on the telephone to Freud, some forty years after the end of their relationship, recalls being struck by how youthful and girlish her mother’s voice became as she spoke to the artist for the last time.

The genesis of the pen and ink drawing that dominates the present sheet is found in Freud’s close friendship with his fellow artist Francis Bacon. For much of their time together, Lucian and Caroline spent a considerable amount of time with Bacon. and after their wedding and their move to a house in Dean Street in Soho, they saw him almost daily. (As Caroline was later to recall, ‘I had dinner with [Bacon] nearly every night for more or less the whole of my marriage to Lucian.’) Caroline remained friendly with Bacon long after the breakup of her marriage to Freud.

This letter dates from the early months of the couple’s courtship. It was, in fact, during a weekend spent with Bacon and his lover Peter Lacy, possibly at Henley-on-Thames in Oxfordshire, that this tender image of the two lovers embracing had its origins. As Freud told the previous owner of this illustrated letter, he was with Caroline in Bacon’s studio when Francis pulled out a camera he had just bought, pointed it at them and called out to Lucian to ‘kiss her’. Freud further recalled that he had just received the photograph from Bacon in the mail, and it was sitting on his desk when he wrote this letter to Caroline. As David Dawson and Martin Gayford have noted of the present sheet, in their recent catalogue of Freud's early letters, ‘It is therefore an example of an initiative from Bacon leading Freud into attempting a subject out of his normal range.’

Some fifty years later, seeing the letter for the first time since he had written it, Freud remarked that it was a very good likeness of her, but that he found his own demeanour somewhat awkward. Perhaps this reaction was due to the uncharacteristic display of vulnerability evident in the image of the artist kissing his lover while he is lost in the moment, his eyes firmly closed. The letter itself underscores the intense nature of this early stage of their relationship. Caroline and Lucian were separated for lengthy stretches during this time due to health issues as well as the machinations of her scheming mother, thus necessitating written correspondence. This letter serves as a testament to the fact that Caroline Blackwood was one of Freud’s great loves, the subject of an all-consuming passion at the time this letter was written. Seeing it again, half a century later, Freud may also have regarded it as an uncomfortable reminder that Caroline was the only woman who had ever left him.

It has been suggested that the ‘Mrs. Mac’ referred to in this letter may be Jean Howard MacGibbon, a children’s book author and wife of the publisher James MacGibbon. The MacGibbons were neighbours of Freud and his first wife Kitty Garman at Clifton Hill in St. John’s Wood, where they had moved in 1948. That same year, James and Jean MacGibbon, together with their friend Robert Kee, set up the publishing firm of MacGibbon and Kee, and a few months later Freud was commissioned by them to provide illustrations for Rex Warner’s book Men and Gods. Freud’s illustrations were, however, rejected by James MacGibbon, and were never used. As Dawson and Gayford point out, as an author of children’s books, Jean MacGibbon was ‘therefore a person likely to hold views on A. A. Milne (which Lucian obviously regarded as too ridiculous for comment).’ They further note of this letter that ‘One can only guess what the bill that he enclosed with his tender love letter, apparently as an afterthought, was for. But there is evidence that at the beginning of 1952 Lucian was (as so often) seriously short of money. At this point, he had a family to support, a new aristocratic lover, a position in high society to maintain, and a gambling habit.’

My dearest Caroline [here is the bill]

I am feeling heavy

with sadness this morning

I can hardly move. I miss

you so much I have

quite forgotten what

you are like. Do please

write to mee and

tell me

anything at

all

Please ask me

to paint you a picture of

something that you would

like. Mrs Mac. keeps on talking

about the poetry of Robert Luis

Stephenson and how very similar

his mind is to that of A.A. Milne.

What can I answer? L.

Datable to the spring or summer of 1952, this is the only known extant letter from Lucian Freud to his lover and future wife, Lady Caroline Blackwood, and was written at the height of his obsession with her. It is especially compelling since the text of the letter surrounds a pen portrait that the artist drew of himself in an embrace with his lover. The portrait of Caroline in this letter captures her unmistakable features; her large, startled eyes and blonde, sweeping hairstyle. Three of Freud’s most compelling painted portraits of Caroline Blackwood, all today in private collections, were executed in 1952, at around the same time as this letter; Girl in Bed and Girl with a Starfish Necklace, as well as a small oil on copper entitled Girl Reading. As has been noted, ‘Lucian Freud’s paintings of Caroline are among the most tender and lyrical portraits he has ever executed.’

Lady Caroline Maureen Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood (1931-1996) first briefly met Freud in 1949 at a party given by the socialite Ann Rothermere. The wife of the press magnate Lord Rothermere, Ann (who would go on to marry her lover, the novelist Ian Fleming, in 1952), was famous for her parties at her homes at Warwick House, near Green Park in London, and at White Cliffs, on St. Margaret’s Bay in Kent, and it was at one of these parties that Freud and Blackwood met again in late 1951. As the artist later recalled, in conversation with Geordie Greig, ‘[Ann Rothermere] asked me to one of those marvellous parties, semi-royal, quite a lot of them were there, and she said, “I hope you find someone you’d like to dance with”, and that sort of thing. And suddenly there was this one person and that was Caroline…She was just exciting in every way and was someone who had taken absolutely no trouble with herself…I went up to her and I danced and danced and I danced and danced...I don’t really think of myself in a dramatic romantic way. I just thought of what I wanted to do, you know, take her home alone, that sort of thing. That night I went home and started painting her.’ In an interview published in 1995, when she was sixty-three, Caroline Blackwood recalled that ‘“Lucian was fantastic, very brilliant, incredibly beautiful, though not in a movie-star way…I remember he was very mannered, he wore these long side whiskers, which nobody else had then. And he wore funny trousers, deliberately. He wanted to stand out in a crowd, and he did.”’

Freud promptly fell deeply in love. Despite the fact that he was married to Kitty Garman and the father of a new baby girl, he pursued Caroline with a passion that bordered on obsession. As Grieg has noted, ‘Ignoring what everyone else thought, as he nearly always did, he was utterly bewitched by Caroline…Lucian adored Caroline’s careless abandon which merged into self-centredness. As an artist, he understood selfishness. In some ways, with Caroline he had met his match.’ As Blackwood’s biographer has written, ‘At eighteen Caroline was fair-haired, dishevelled, slender, athletic, intense, puckish, and shy. She no doubt satisfied Lucian’s aesthetic sense, but she also possessed intelligence and courage. And, perhaps equally important, she was an aristocrat and a Guinness heiress.’

Despite the severe disapproval of her mother, the Dowager Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava, Caroline eloped with Freud to Paris in 1952. Something of the intensity of the couple’s relationship in captured in a letter from the writer and biographer James Pope-Hennessy to his friend Nolwen de Janzé, written from London at the end of September 1953: ‘Lucian and Caroline turned up here unexpectedly this morning, had baths and breakfast and wandered away again…They were sweet, but like somnambulists and wrapped in that impenetrable unawareness of people in love – do you know what I mean? - entirely unaware of the outside world, and rather expecting everybody else to do things for them. People in love are rather like royalty, I think. I can’t see any sense whatever in their marrying; but this, in Paris, they propose to do.’ Freud and Blackwood were married in London a few weeks later, on December 9th, 1953, a day after the artist’s thirty-first birthday.

By 1956, however, the marriage was in difficulties, with Caroline increasingly unhappy. That year she had left him and fled to Rome, eventually filing for divorce in 1957. By most accounts, Freud was devastated by Caroline’s decision to abandon the marriage, and was left deeply unhappy. (Both the artist Michael Andrews and the art critic David Sylvester later recalled that this was the only time they had ever seen Freud weeping.) As the artist’s biographer has noted, ‘Freud felt injured as well as distraught. Not so much because it was she who had left but because, ultimately, she had gone even further than he in nullifying the marriage. “Things could have been better for her with different behaviour on my part...”’ The writer and diarist Joan Wyndham, who had had a brief affair with Freud in 1945, later opined that ‘Caroline was the great love of Lucian’s life…With Caroline he behaved terribly well. Very unusual. He didn’t love any of us, really…he must have known that she loved him, which was a great thing.’ This period also seems to have led to a change in the way the artist depicted women in his paintings, with much less of the tenderness found in the earlier portraits. As Caroline herself noted, ‘Lucian’s painting changed violently after I left him…Lucian painted me in a different way to how he’s painting other people. There’s much more lyricism in these early works.’

Following the divorce, Caroline – who never seems to have spoken badly of Freud throughout the rest of her life – became a gifted writer, and in later years was married to two equally brilliant men; the composer Israel Citkowitz and the poet Robert Lowell. In January 1996, when she had been diagnosed with an inoperable cancer and had checked into the Mayfair Hotel in New York to spend her final weeks, Freud phoned her from London and they had a long conversation. Caroline’s daughter Ivana Lowell, listening to her mother speaking on the telephone to Freud, some forty years after the end of their relationship, recalls being struck by how youthful and girlish her mother’s voice became as she spoke to the artist for the last time.

The genesis of the pen and ink drawing that dominates the present sheet is found in Freud’s close friendship with his fellow artist Francis Bacon. For much of their time together, Lucian and Caroline spent a considerable amount of time with Bacon. and after their wedding and their move to a house in Dean Street in Soho, they saw him almost daily. (As Caroline was later to recall, ‘I had dinner with [Bacon] nearly every night for more or less the whole of my marriage to Lucian.’) Caroline remained friendly with Bacon long after the breakup of her marriage to Freud.

This letter dates from the early months of the couple’s courtship. It was, in fact, during a weekend spent with Bacon and his lover Peter Lacy, possibly at Henley-on-Thames in Oxfordshire, that this tender image of the two lovers embracing had its origins. As Freud told the previous owner of this illustrated letter, he was with Caroline in Bacon’s studio when Francis pulled out a camera he had just bought, pointed it at them and called out to Lucian to ‘kiss her’. Freud further recalled that he had just received the photograph from Bacon in the mail, and it was sitting on his desk when he wrote this letter to Caroline. As David Dawson and Martin Gayford have noted of the present sheet, in their recent catalogue of Freud's early letters, ‘It is therefore an example of an initiative from Bacon leading Freud into attempting a subject out of his normal range.’

Some fifty years later, seeing the letter for the first time since he had written it, Freud remarked that it was a very good likeness of her, but that he found his own demeanour somewhat awkward. Perhaps this reaction was due to the uncharacteristic display of vulnerability evident in the image of the artist kissing his lover while he is lost in the moment, his eyes firmly closed. The letter itself underscores the intense nature of this early stage of their relationship. Caroline and Lucian were separated for lengthy stretches during this time due to health issues as well as the machinations of her scheming mother, thus necessitating written correspondence. This letter serves as a testament to the fact that Caroline Blackwood was one of Freud’s great loves, the subject of an all-consuming passion at the time this letter was written. Seeing it again, half a century later, Freud may also have regarded it as an uncomfortable reminder that Caroline was the only woman who had ever left him.

It has been suggested that the ‘Mrs. Mac’ referred to in this letter may be Jean Howard MacGibbon, a children’s book author and wife of the publisher James MacGibbon. The MacGibbons were neighbours of Freud and his first wife Kitty Garman at Clifton Hill in St. John’s Wood, where they had moved in 1948. That same year, James and Jean MacGibbon, together with their friend Robert Kee, set up the publishing firm of MacGibbon and Kee, and a few months later Freud was commissioned by them to provide illustrations for Rex Warner’s book Men and Gods. Freud’s illustrations were, however, rejected by James MacGibbon, and were never used. As Dawson and Gayford point out, as an author of children’s books, Jean MacGibbon was ‘therefore a person likely to hold views on A. A. Milne (which Lucian obviously regarded as too ridiculous for comment).’ They further note of this letter that ‘One can only guess what the bill that he enclosed with his tender love letter, apparently as an afterthought, was for. But there is evidence that at the beginning of 1952 Lucian was (as so often) seriously short of money. At this point, he had a family to support, a new aristocratic lover, a position in high society to maintain, and a gambling habit.’

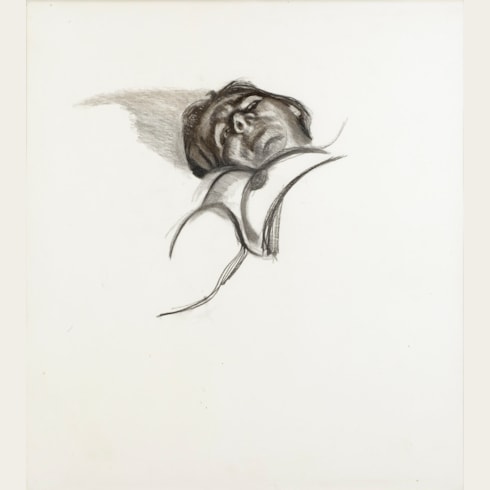

The early years of Lucian Freud’s career were largely devoted to drawing, and the practice would remain a vital part of the artist’s development throughout the 1940’s and early 1950’s. As Freud himself recalled, many years later, ‘I would have thought I did 200 drawings to every painting in those early days. I very much prided myself on my drawing. My work was in a sense very linear.’ The 1940’s in particular were a period of sustained activity in drawing, with the artist creating an important series of self-contained works in charcoal, ink, watercolour, coloured crayons, pencil and chalk. As Lawrence Gowing has noted, ‘Freud’s drawings in 1943 and 1944 have already a quality of resolved classical line, with the minimum of inflexions to make legible its formal message, which is otherwise the property of only the very best painters of twenty years before...Style and capacity developed rapidly in these drawings...’ William Feaver further comments that ‘By the mid-1940’s, Freud’s drawings had an extraordinary allure. In charcoal, conté and chalk on Ingres paper he caught every texture from bamboo to corduroy...’

Freud had his first solo exhibition at the Lefevre Gallery in London in the winter of 1944, followed by a second show in early 1946, and in both exhibitions a number of drawings were shown. Writing of the artist’s drawings of this period, Robert Hughes noted of Freud that ‘there is no doubt that part of his reputation as a boy prodigy in London art circles in the war years rested on his single-minded commitment to linear description rather than painterly evocation…The precocity of the early work, some of which...reveals a degree of control extraordinary in an artist of 21, lies in the fierce independence of its delineation.’ However, by the middle of the 1950’s the artist had abandoned drawing altogether, fearing that the predominantly linear, graphic quality of his paintings was impeding his brushwork. Since then he produced drawings relatively infrequently, and certainly without the sustained productivity of the 1940’s and early 1950’s. The medium of etching, in many respects, took the place of drawing as his preferred graphic medium.

Provenance

Given by the artist to Lady Caroline Blackwood, London

Given by her to a friend, and thence by descent to his daughter

Anonymous sale, London, Sotheby’s Olympia, 21 March 2002, lot 527

Private collection, London.

Given by her to a friend, and thence by descent to his daughter

Anonymous sale, London, Sotheby’s Olympia, 21 March 2002, lot 527

Private collection, London.

Literature

David Dawson and Martin Gayford, Love Lucian: The Letters of Lucian Freud 1939-1954, London, 2022, pp.339-340; Stephen Smith, ‘Paper trail: Lucian Freud’s revealing, charming letters’, The Art Newspaper, November 2022, p.69 (illustrated).