Henry MOORE

(Castleford 1898 - Much Hadham 1986)

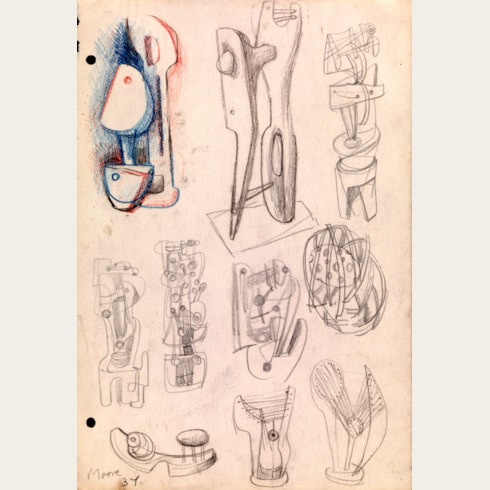

Group of Seated Figures

Pen and ink, wax crayon and charcoal over watercolour, heightened with white.

Signed and dated Moore / 42 in black chalk at the lower left.

332 x 559 mm. (13 1/8 x 22 in.)

Henry Moore Foundation archive number HMF 2100a.

Signed and dated Moore / 42 in black chalk at the lower left.

332 x 559 mm. (13 1/8 x 22 in.)

Henry Moore Foundation archive number HMF 2100a.

In a recent monograph on Henry Moore’s drawings, Andrew Causey points out that ‘There is a wealth of fantasy and imagination in Moore’s drawings that was never realised in sculpture. As a sculptor Moore was austere and quite cautious...As a draughtsman...[he] was able to work fast with ideas flooding onto the paper, ideas related to sculpture but which he established and embellished with detail that was essentially pictorial...Sculpture for Moore was a highly considered and perfected art, and he seems to have found, especially during the 1930s and 1940s, that pictorial art gave free range to his imagination more readily than sculpture did.’ Moore himself once stated that ‘My drawings are done mainly as a help towards making sculpture, as a means of generating ideas for sculpture, tapping oneself for the initial idea; and as a way of sorting out ideas and developing them.’

Drawn in 1942, the present sheet can be associated with a series of drawings of groups of seated or standing draped figures that derive from Moore’s shelter drawings made during the first years of the war, in 1940 and 1941. As Kenneth Clark noted of the drawings produced by Moore during this fertile period, ‘he showed not only insight and compassion, but marvellous graphic skill. Since circumstances kept him from his sculpture, he became in effect a painter…but, as was to be expected, his renderings of the human body are given weight and substance, and related to each other like great sculpture. Many of the poses and groups that he discovered were made into full-size drawings, but practically all of them occur in the two notebooks5that are, to my mind, amoing the most precious works of art of the present century…By 1941 he began to feel the need of turning his recorded experiences back into forms that seemed to him grander and more durable, and are certainly more in keeping with the general line of his development. The resulting drawings are perhaps the finest things in all his graphic work.’

Among the most significant of Henry Moore’s wartime drawings, this very large sheet has remained relatively little-known, having been kept in two private collections in Switzerland since at least the 1980s, and has been exhibited just once, in Martigny in 1989. While not a shelter drawing itself, it was almost certainly inspired by the groups of figures that the artist had studied in the Underground stations and at Tilbury, a vast shelter in Whitechapel in the East End that was the single largest air-raid shelter in London. Drawn in a rich combination of media, including wax crayons, stumped charcoal and watercolour washes, it may be compared with a small number of similarly large and highly finished drawings completed the previous year, such as Tilbury Shelter: Group of Draped Figures, in the Hiroshima Prefectural Art Museum in Japan, Group of Shelterers During an Air Raid in the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto and Group of Draped Figures in a Shelter in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation.

As Moore once stated, in a note to Kenneth Clark written in the early 1970s, ‘the experience and struggle in the exploring of form that one has continually tried to make in sculpture, as well as the way of thinking three-dimensionally…has usually been the aim in most of my drawings…If for any reason I’m unable to go on doing sculpture – then I know that drawing could satisfy me for the rest of my days.’

Drawn in 1942, the present sheet can be associated with a series of drawings of groups of seated or standing draped figures that derive from Moore’s shelter drawings made during the first years of the war, in 1940 and 1941. As Kenneth Clark noted of the drawings produced by Moore during this fertile period, ‘he showed not only insight and compassion, but marvellous graphic skill. Since circumstances kept him from his sculpture, he became in effect a painter…but, as was to be expected, his renderings of the human body are given weight and substance, and related to each other like great sculpture. Many of the poses and groups that he discovered were made into full-size drawings, but practically all of them occur in the two notebooks5that are, to my mind, amoing the most precious works of art of the present century…By 1941 he began to feel the need of turning his recorded experiences back into forms that seemed to him grander and more durable, and are certainly more in keeping with the general line of his development. The resulting drawings are perhaps the finest things in all his graphic work.’

Among the most significant of Henry Moore’s wartime drawings, this very large sheet has remained relatively little-known, having been kept in two private collections in Switzerland since at least the 1980s, and has been exhibited just once, in Martigny in 1989. While not a shelter drawing itself, it was almost certainly inspired by the groups of figures that the artist had studied in the Underground stations and at Tilbury, a vast shelter in Whitechapel in the East End that was the single largest air-raid shelter in London. Drawn in a rich combination of media, including wax crayons, stumped charcoal and watercolour washes, it may be compared with a small number of similarly large and highly finished drawings completed the previous year, such as Tilbury Shelter: Group of Draped Figures, in the Hiroshima Prefectural Art Museum in Japan, Group of Shelterers During an Air Raid in the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto and Group of Draped Figures in a Shelter in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation.

As Moore once stated, in a note to Kenneth Clark written in the early 1970s, ‘the experience and struggle in the exploring of form that one has continually tried to make in sculpture, as well as the way of thinking three-dimensionally…has usually been the aim in most of my drawings…If for any reason I’m unable to go on doing sculpture – then I know that drawing could satisfy me for the rest of my days.’

Drawing was at the centre of Henry Moore’s artistic practice. Over the course of his long career, he made over seven thousand drawings, many of these as part of sketchbooks (though the artist preferred the term ‘notebooks’). Moore’s myriad drawings – studies from life, copies after the work of earlier artists, studies of objects from nature and, most significantly, studies and ideas for sculptures – seem to have always been regarded by the artist, as well as by contemporary scholars and artists, as significant works of art in their own right. They were included in exhibitions of his work from the very start of his career; indeed, his first solo exhibition, at the Warren Gallery in London in 1928, included fifty-one drawings alongside forty-two sculptures. (Several drawings from the exhibition were acquired by the curator and art historian Kenneth Clark – who was to become one of Moore’s most fervent supporters – as well as the artists Jacob Epstein, Henry Lamb and Augustus John.) Moore’s second one-man show, at the Leicester Galleries in 1931, included thirty-four sculptures and nineteen drawings. In later years, a number of gallery and museum exhibitions were devoted solely to Moore’s drawings, the first being held at the Zwemmer Gallery in London in 1935. As further evidence of his desire to have his drawings regarded as autonomous works of art, Moore often unbound his sketchbooks and sold the individual drawings to collectors.

During much of the early part of the Second World War, when commissions were few and materials for stone or wood sculpture hard to come by, Moore poured his energy into drawing. The most significant of these works, and certainly the best known, were the so-called shelter drawings, made in London in the early 1940s. Depicting people taking refuge in London Undergound stations during the nightly bombing of London during the Blitz, they were mostly drawn from memory on the basis of sketches and notes made on the spot. Moore continued to produce these shelter drawings when he left London for the village of Perry Green, near Much Hadham in Hertfordshire, when his home in Hampstead in north London was damaged during the Blitz. The shelter drawings soon came to the attention of Kenneth Clark, by then the Director of the National Gallery, as well as Surveyor of the King’s Pictures and Chairman of the War Artists Advisory Committee. Clark commissioned Moore to create a series of shelter drawings as an official War Artist, and several were exhibited at the National Gallery in London in 1941. They are today regarded as among the artist’s greatest achievements as a draughtsman.

Moore returned to sculpture in 1943, and continued to generate most of his ideas through the practice of drawing. As Andrew Causey has noted, ‘He did not use drawing to resolve parts of sculptures he planned to make: his drawings for sculptures are always of finished objects, and he rarely seems to have worked on sculptures with drawings around him, as if, once he had decided on the result he was looking for, drawing was no longer useful. To that extent drawing and sculpture were separate practices: one began where the other ended.’ In the 1950s, Moore’s growing international success, and the increasing number of commissions he received, led to a considerable decline in the amount of drawings he produced. He began to concentrate on sculpture, using drawings mainly to develop ideas for specific works rather than as a means of experimentation. (He also created designs for sculpture in the form of clay or plaster maquettes.) With the exception of the shelter drawings he produced during the Second World War, however, Moore rarely gave specific or descriptive titles to his drawings, preferring to exhibit them under generic titles such as ‘Drawings for Sculpture’, ‘Drawings for Carving’, ‘Ideas for Sculpture’, and so forth.

During much of the early part of the Second World War, when commissions were few and materials for stone or wood sculpture hard to come by, Moore poured his energy into drawing. The most significant of these works, and certainly the best known, were the so-called shelter drawings, made in London in the early 1940s. Depicting people taking refuge in London Undergound stations during the nightly bombing of London during the Blitz, they were mostly drawn from memory on the basis of sketches and notes made on the spot. Moore continued to produce these shelter drawings when he left London for the village of Perry Green, near Much Hadham in Hertfordshire, when his home in Hampstead in north London was damaged during the Blitz. The shelter drawings soon came to the attention of Kenneth Clark, by then the Director of the National Gallery, as well as Surveyor of the King’s Pictures and Chairman of the War Artists Advisory Committee. Clark commissioned Moore to create a series of shelter drawings as an official War Artist, and several were exhibited at the National Gallery in London in 1941. They are today regarded as among the artist’s greatest achievements as a draughtsman.

Moore returned to sculpture in 1943, and continued to generate most of his ideas through the practice of drawing. As Andrew Causey has noted, ‘He did not use drawing to resolve parts of sculptures he planned to make: his drawings for sculptures are always of finished objects, and he rarely seems to have worked on sculptures with drawings around him, as if, once he had decided on the result he was looking for, drawing was no longer useful. To that extent drawing and sculpture were separate practices: one began where the other ended.’ In the 1950s, Moore’s growing international success, and the increasing number of commissions he received, led to a considerable decline in the amount of drawings he produced. He began to concentrate on sculpture, using drawings mainly to develop ideas for specific works rather than as a means of experimentation. (He also created designs for sculpture in the form of clay or plaster maquettes.) With the exception of the shelter drawings he produced during the Second World War, however, Moore rarely gave specific or descriptive titles to his drawings, preferring to exhibit them under generic titles such as ‘Drawings for Sculpture’, ‘Drawings for Carving’, ‘Ideas for Sculpture’, and so forth.

Provenance

Private collection (W. D. Alder?), Ruvigliana, Canton Ticino, Switzerland, in 1989

Anonymous sale, Bern, Galerie Kornfeld, 24 June 1994, lot 96

Galerie Kornfeld, Bern

Eberhard Kornfeld, Bern (Lugt 913b)

Thence by descent.

Anonymous sale, Bern, Galerie Kornfeld, 24 June 1994, lot 96

Galerie Kornfeld, Bern

Eberhard Kornfeld, Bern (Lugt 913b)

Thence by descent.

Literature

David Mitchinson, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Martigny, 1989, illustrated p.146; Ann Garrould, ed., Henry Moore: Complete Drawings. Vol.3: 1940-49, Much Hadham and London, 2001, p.173, no.AG 42.212 (HMF 2100a).

Exhibition

Martigny, Fondation Pierre Gianadda, Henry Moore, 1989, unnumbered.