Gwen JOHN

(Haverfordwest 1876 - Dieppe 1939)

Two Women at Church, Meudon

Watercolour over a pencil underdrawing.

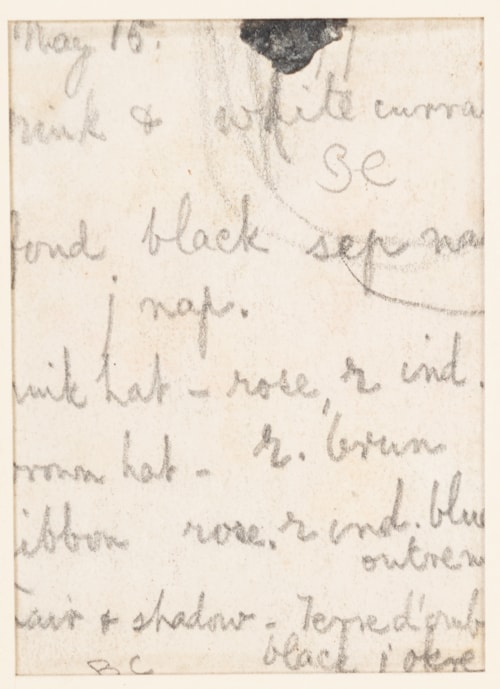

Dated and inscribed by the artist with colour notes 'May 15/ pink & white curra- / fond black sep na- / i. nap. / pink hat – rose, r ind. / brown hat - r. brun / ribbon rose. r. ind. blue / outrem- / hair & shadow – terre d’omb / black i ochre' in pencil on the verso.

67 x 51 mm. (2 7/8 x 2 in.)

Dated and inscribed by the artist with colour notes 'May 15/ pink & white curra- / fond black sep na- / i. nap. / pink hat – rose, r ind. / brown hat - r. brun / ribbon rose. r. ind. blue / outrem- / hair & shadow – terre d’omb / black i ochre' in pencil on the verso.

67 x 51 mm. (2 7/8 x 2 in.)

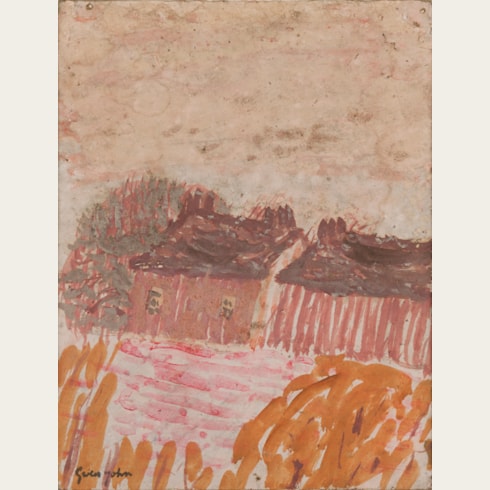

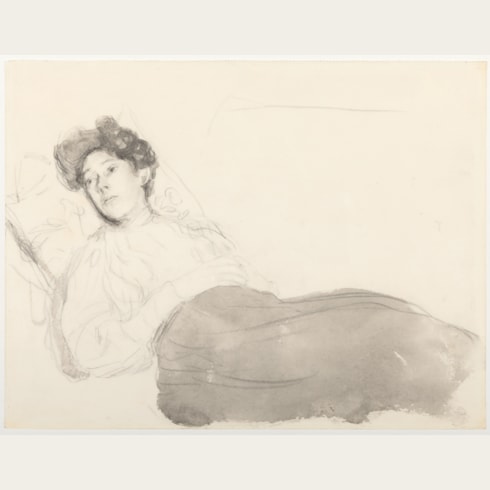

Datable to the 1920s, the present sheet was probably made in a small sketchbook while Gwen John attended services in the church at Meudon, which she did regularly following her conversion to Catholicism in 1913. Her drawings of the congregation at Meudon are usually back or side views of people seated in front or near her, usually in small groups or as single figures. As one of the artist’s biographers records, ‘Louise Roche, a neighbour in Meudon, remembered a vespers service around 1923 when a woman in a broad-brimmed felt hat and a long dark cloak slid discreetly to the back of the church and there, instead of kneeling, commenced to draw in a sketch-book throughout the service. When Madame Roche heard that the strange creature was a convert, and an English one at that, she thought no more of the matter. Gwen John was in fact making what she called ‘the little drawings in colour I do.’…These gouaches…are the most personal things Gwen John ever made.’

A more recent biography has noted that ‘The Meudon Curé was shocked by her appearing with her sketchbook to draw the other churchgoers and instructed her that what she was doing was wrong…Gwen John was unmoved. In a draft letter to [her friend Véra] Oumançoff she wrote: ‘When I told you I am going to continue to draw at Vespers, evening services and retreats I wanted to vex you, I don’t know why. I regret having told you that because I’m going to carry on, I think…Like everyone else I like to pray in church, but my spirit is not able to pray for a long time at a stretch…The orphans with those black hats with white ribbons and their black dresses with little white collars charm me, and the others charm me in church. If I cut off all that there would not be enough happiness in my life.’…The watercolour and gouache paintings of the Meudon congregants – nuns, orphans and others – that emerged from Gwen John’s refusal to obey the Curé cannot but make one relieved that she did not listen. They have a deftness and wit about them, a wonderful clarity and simplicity of line and colour.’

As another writer has pointed out, ‘There are more drawings of people in church than of any other single subject. The church pictures reflect the circumstances of their production. They are small in scale – small enough to have been drawn on the pages of pocket sketch-books – and most are done in watercolour or gouache over an underdrawing in pencil or, occasionally, charcoal. It seems improbable that she would have encumbered herself in church with the paraphernalia of the watercolour artist and the pictures themselves suggest that the colour was added in the studio. Almost every subject is repeated several times over (in some cases more than a dozen times). Sometimes there is only the slightest of variations between one of these repetitions and the next; at other times the repetitions incorporate important changes in tone, in colour, and in composition. In other words, many of these little pictures, for all their lively observation of fact, are reflective experiments in form and structure.’ The John scholar Cecily Langdale adds that, ‘The church drawings are both reticent and intimate; their subjects, usually seen from behind, are captured in an essentially private moment. In design, palette, scale and subject, these drawings are in the French intimiste tradition.’

Among closely related works is a slightly larger gouache drawing of a girl and a woman with prayer books in church, which was formerly in the collection of Catherine Auchincloss and was sold at auction in 2018, and a very similar gouache and watercolour study of two women wearing hats, shown at the Gwen John memorial exhibition in London in 1946, which appeared at auction in 2017.

A more recent biography has noted that ‘The Meudon Curé was shocked by her appearing with her sketchbook to draw the other churchgoers and instructed her that what she was doing was wrong…Gwen John was unmoved. In a draft letter to [her friend Véra] Oumançoff she wrote: ‘When I told you I am going to continue to draw at Vespers, evening services and retreats I wanted to vex you, I don’t know why. I regret having told you that because I’m going to carry on, I think…Like everyone else I like to pray in church, but my spirit is not able to pray for a long time at a stretch…The orphans with those black hats with white ribbons and their black dresses with little white collars charm me, and the others charm me in church. If I cut off all that there would not be enough happiness in my life.’…The watercolour and gouache paintings of the Meudon congregants – nuns, orphans and others – that emerged from Gwen John’s refusal to obey the Curé cannot but make one relieved that she did not listen. They have a deftness and wit about them, a wonderful clarity and simplicity of line and colour.’

As another writer has pointed out, ‘There are more drawings of people in church than of any other single subject. The church pictures reflect the circumstances of their production. They are small in scale – small enough to have been drawn on the pages of pocket sketch-books – and most are done in watercolour or gouache over an underdrawing in pencil or, occasionally, charcoal. It seems improbable that she would have encumbered herself in church with the paraphernalia of the watercolour artist and the pictures themselves suggest that the colour was added in the studio. Almost every subject is repeated several times over (in some cases more than a dozen times). Sometimes there is only the slightest of variations between one of these repetitions and the next; at other times the repetitions incorporate important changes in tone, in colour, and in composition. In other words, many of these little pictures, for all their lively observation of fact, are reflective experiments in form and structure.’ The John scholar Cecily Langdale adds that, ‘The church drawings are both reticent and intimate; their subjects, usually seen from behind, are captured in an essentially private moment. In design, palette, scale and subject, these drawings are in the French intimiste tradition.’

Among closely related works is a slightly larger gouache drawing of a girl and a woman with prayer books in church, which was formerly in the collection of Catherine Auchincloss and was sold at auction in 2018, and a very similar gouache and watercolour study of two women wearing hats, shown at the Gwen John memorial exhibition in London in 1946, which appeared at auction in 2017.

Born in Wales, Gwendolyn Mary John was the second of four children, and was drawing from an early age. In 1895 she began a course of study at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, where her younger brother Augustus had enrolled the previous year. Both Johns remained at the Slade until 1898, with Augustus gaining recognition as one of the outstanding draughtsmen of his generation and soon enjoying success and notoriety. After leaving the Slade in 1898, Gwen spent six months in Paris, studying at James McNeill Whistler’s short-lived school of painting, the Académie Carmen, alongside two contemporaries from the Slade, Ida Nettleship and Gwen Salmond. Back in London, she exhibited twice yearly at the New English Art Club between 1900 and 1902, and also showed three paintings as part of an exhibition of Augustus’s work in London in 1903. The following year, at the age of twenty-seven and accompanied by her friend, the artist Dorelia McNeill, John settled in Montparnasse in Paris, where she earned a living by modelling for artists. One of these was the renowned sculptor Auguste Rodin, with whom John had a long and intense love affair that lasted some ten years, although the true nature of their relationship was known only to a handful of the sculptor’s close friends.

John lived in France for the remainder of her career, over the course of which she produced fewer than two hundred paintings as well as numerous drawings; her subjects were mainly portraits of solitary women and girls, as well as occasional landscapes, interiors and still life compositions. She worked in Montparnasse for seven years, occasionally sending her paintings back to London to be shown at the NEAC, and in 1911 moved to Meudon, in the southwestern suburbs of Paris and near Rodin’s country house, although she kept a studio in Paris and spent several summers in Brittany. By this time she had been introduced by Augustus to John Quinn, a prominent American collector of modern art, who began to acquire her paintings and drawings and was to become her most significant patron. From 1912 onwards Quinn sent her a yearly stipend in exchange for her work, and between 1911 and his death in 1924 he acquired almost every painting she wished to sell, eventually coming to own some twenty paintings and around fifty drawings by the artist. (He also lent a painting by her – the only one he owned at the time - to the seminal Armory Show of modern art in New York in 1913, which he had helped to organize.) In 1913 John converted to Roman Catholicism, and from this point began to figure prominently in her work, mainly in paintings and small-scale gouaches of figures at Mass.

Throughout her career John worked mostly in isolation, having preferred to withdraw from both society and artistic circles, first in London and later in Paris. (As one scholar has noted of the artist, ‘She cultivated privacy, and a sense of privacy is one of the dominant feelings of her painting...she always worked in solitude, and took only the little she wanted from the great years of the modern movement in the arts.’) Although John continued to show at the NEAC in London and also exhibited at the Salon des Tuileries and the Salon d’Automne in Paris, she worked mainly for herself and seems to been largely unconcerned with making her work better known. Only one solo exhibition was held in her lifetime, at the New Chenil Galleries in London in 1926, which included over forty paintings and watercolours and some albums of drawings. Although John appears to have painted relatively little after this date, by 1930 works by her were already in the collections of the Tate Gallery in London, the Manchester City Art Gallery and the Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester, the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York.

Gwen John’s beautiful, enigmatic and delicately painted intimist works are almost always modest in scale and subdued in tonality. She painted very slowly and her never signed or dated her work, so establishing a chronology for her oeuvre is not always straightforward. She also often repeated a composition, sometimes producing several variants of a particularly successful work. By around 1930, however, she had largely ceased to paint, although she continued to draw. Her last datable work was done in 1933, and she seems to have stopped working almost entirely for the last five or six years of her life. At John’s death in 1939, at the age of sixty-three, the vast majority of her output remained in her ramshackle studio in Meudon, and was inherited by her nephew Edwin John, the son of Gwen’s brother Augustus. The following year an exhibition of paintings and drawings from the artist’s estate was held under the auspices of the Matthiesen Gallery in London; this was followed in 1947 by a large retrospective exhibition held at the same gallery and later at the Arts Council.

Although over the course of her career Gwen John was always overshadowed by her younger brother Augustus, a larger-than-life character who enjoyed success and notoriety, in recent years her critical reputation has come to surpass his, and she has been celebrated as one of the most significant British artists of the 20th century. Indeed, this is something Augustus had foretold, once stating that ‘In fifty years’ time I will be known as the brother of Gwen John.’

John lived in France for the remainder of her career, over the course of which she produced fewer than two hundred paintings as well as numerous drawings; her subjects were mainly portraits of solitary women and girls, as well as occasional landscapes, interiors and still life compositions. She worked in Montparnasse for seven years, occasionally sending her paintings back to London to be shown at the NEAC, and in 1911 moved to Meudon, in the southwestern suburbs of Paris and near Rodin’s country house, although she kept a studio in Paris and spent several summers in Brittany. By this time she had been introduced by Augustus to John Quinn, a prominent American collector of modern art, who began to acquire her paintings and drawings and was to become her most significant patron. From 1912 onwards Quinn sent her a yearly stipend in exchange for her work, and between 1911 and his death in 1924 he acquired almost every painting she wished to sell, eventually coming to own some twenty paintings and around fifty drawings by the artist. (He also lent a painting by her – the only one he owned at the time - to the seminal Armory Show of modern art in New York in 1913, which he had helped to organize.) In 1913 John converted to Roman Catholicism, and from this point began to figure prominently in her work, mainly in paintings and small-scale gouaches of figures at Mass.

Throughout her career John worked mostly in isolation, having preferred to withdraw from both society and artistic circles, first in London and later in Paris. (As one scholar has noted of the artist, ‘She cultivated privacy, and a sense of privacy is one of the dominant feelings of her painting...she always worked in solitude, and took only the little she wanted from the great years of the modern movement in the arts.’) Although John continued to show at the NEAC in London and also exhibited at the Salon des Tuileries and the Salon d’Automne in Paris, she worked mainly for herself and seems to been largely unconcerned with making her work better known. Only one solo exhibition was held in her lifetime, at the New Chenil Galleries in London in 1926, which included over forty paintings and watercolours and some albums of drawings. Although John appears to have painted relatively little after this date, by 1930 works by her were already in the collections of the Tate Gallery in London, the Manchester City Art Gallery and the Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester, the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York.

Gwen John’s beautiful, enigmatic and delicately painted intimist works are almost always modest in scale and subdued in tonality. She painted very slowly and her never signed or dated her work, so establishing a chronology for her oeuvre is not always straightforward. She also often repeated a composition, sometimes producing several variants of a particularly successful work. By around 1930, however, she had largely ceased to paint, although she continued to draw. Her last datable work was done in 1933, and she seems to have stopped working almost entirely for the last five or six years of her life. At John’s death in 1939, at the age of sixty-three, the vast majority of her output remained in her ramshackle studio in Meudon, and was inherited by her nephew Edwin John, the son of Gwen’s brother Augustus. The following year an exhibition of paintings and drawings from the artist’s estate was held under the auspices of the Matthiesen Gallery in London; this was followed in 1947 by a large retrospective exhibition held at the same gallery and later at the Arts Council.

Although over the course of her career Gwen John was always overshadowed by her younger brother Augustus, a larger-than-life character who enjoyed success and notoriety, in recent years her critical reputation has come to surpass his, and she has been celebrated as one of the most significant British artists of the 20th century. Indeed, this is something Augustus had foretold, once stating that ‘In fifty years’ time I will be known as the brother of Gwen John.’

Provenance

The estate of the artist

By descent to the artist’s nephew, Edwin John (Inv. EJ 610)

Anonymous sale, London, Phillips, 17 July 2001, lot 30

Anonymous sale, London, Bonham’s, 30 June 2010, lot 108

Anonymous sale, London, Roseberys, 11 February 2020, lot 10

Private collection, London.

By descent to the artist’s nephew, Edwin John (Inv. EJ 610)

Anonymous sale, London, Phillips, 17 July 2001, lot 30

Anonymous sale, London, Bonham’s, 30 June 2010, lot 108

Anonymous sale, London, Roseberys, 11 February 2020, lot 10

Private collection, London.

Exhibition

London, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, Gwen John 1876-1939, March 1976, part of no.54 (‘Six small church groups. Pencil, ink, watercolour and gouache. From 2 5/8 x 2 in to 3 5/8 x 2 3/4 in.’); Chichester, Pallant House Gallery, Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris, 2023, unnumbered.