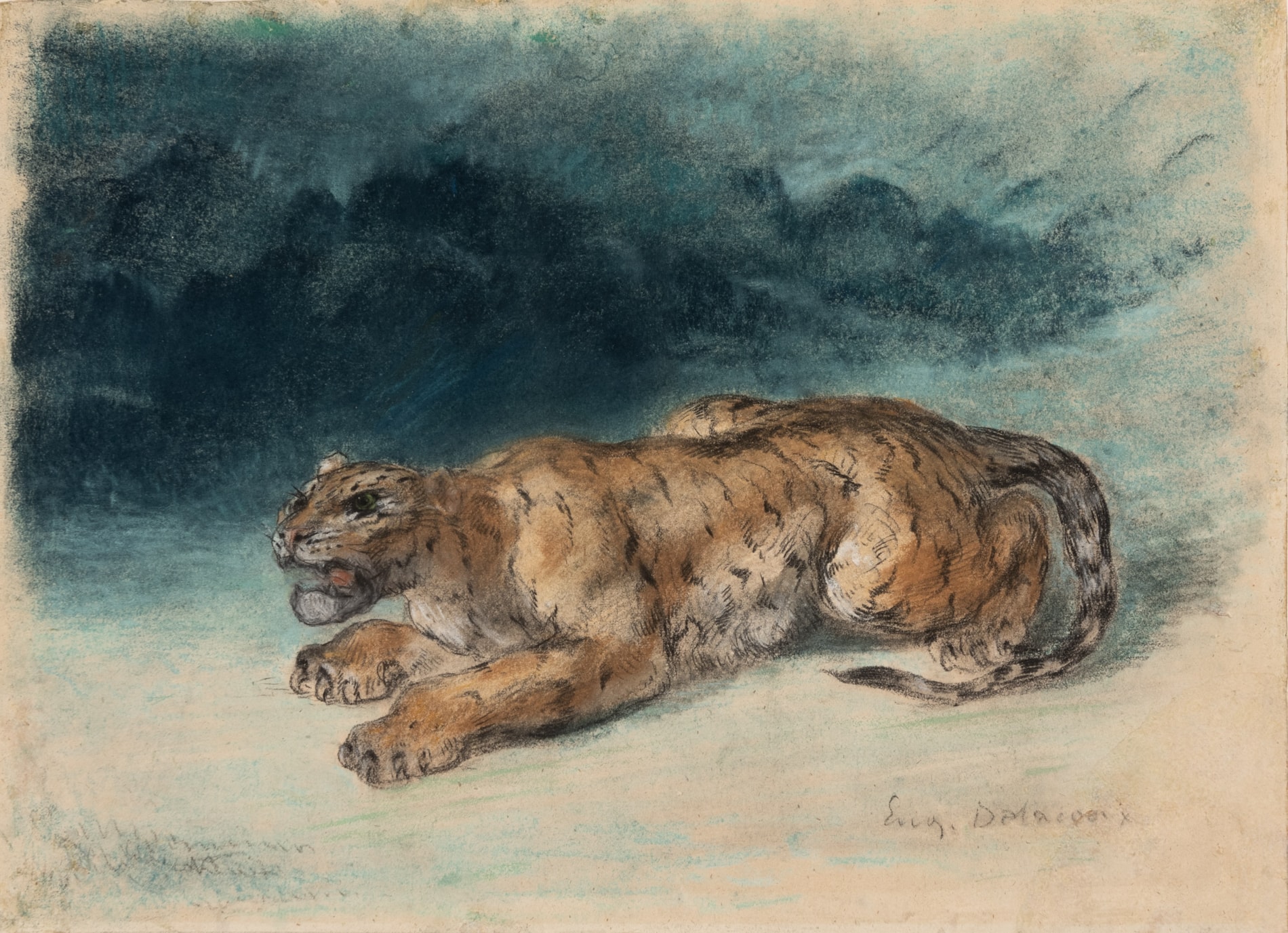

Eugène DELACROIX

(Charenton-Saint Maurice 1798 - Paris 1863)

A Tiger Preparing to Pounce

Pastel.

Signed Eug. Delacroix in pencil at the lower right.

A made up area at the lower right corner of the sheet.

232 x 322 mm. (9 1/8 x 12 5/8 in.)

Signed Eug. Delacroix in pencil at the lower right.

A made up area at the lower right corner of the sheet.

232 x 322 mm. (9 1/8 x 12 5/8 in.)

Eugène Delacroix had an abiding interest in the study and representation of wild animals, inspired by such earlier works as the paintings of lion hunts by Rubens and the drawings and prints of George Stubbs and James Ward. In the late 1820s, he began to make regular visits, often in the company of the animalier sculptor Antoine-Louis Barye, to the Jardin des Plantes of the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. There he made numerous studies of animals, and in particular the wild animals and beasts of prey that were kept there, while in the summer of 1829, the two artists were also given permission to draw from the carcass of a dead lion at the Jardin des Plantes.) Delacroix continued to make study drawings of wild animals from life well into his later career. These studies of felines in particular became the basis for a number of lithographs, as well as for the paintings of lions and tigers that began to occur frequently in his work from the 1840s onwards, culminating in the remarkable paintings of lion hunts executed between 1854 and 1861. In the words of an anonymous contemporary art critic, writing of Delacroix in 1830, ‘This curious artist has never painted a man who looked as much like a man as his tiger looks like a tiger.’

As the scholar Vincent Pomarède has noted, from 1840 ‘Delacroix tried his hand at a new genre, a sort of pictorial transposition of Barye’s animal sculptures enhanced by his imagination and his personal technical concerns…his aesthetic intentions [were] to render the animals’ physical demeanor, to paint their coats using bright and lively colors, to enliven compositions with anecdotal material – creating a serene effect when the feline is resting and a violent one when it is shown devouring its prey – and to blend the depiction of the animal into a richly elaborated landscape. The quantity and quality of these animal scenes made after 1850 indicate that they had become a veritable obsession – a consequence, undoubtedly, of Delacroix’s aesthetic motivations during the final phase of his career…’ As another scholar has written, ‘Delacroix’s animal drawings range from synoptic studies to more finished renderings...He was responsive to the full range of feline behavior, from the almost humanly affectionate interaction of a lioness playing with her cubs...to the predatory beast stalking and attacking its prey.’

A closely related small painting of a Lioness Ready to Spring, signed and dated 1863, is in the Louvre. The pose of the lioness in the painting, which was completed shortly before the artist’s death, differs from that of the tiger in the present pastel mainly in the position of the creature’s tail. As has been noted, the Louvre painting ‘distills the essence of [Delacroix’s] animal studies…He sought a perfect synthesis between an austere treatment of the landscape…and the quiet power of the feline poised to spring. Simply and effectively, he depicted the animal’s physical stance, combining its power and agility with the beauty of its coat, over which his brush lingered without becoming mired in anatomical details…Purposefully eschewing gratuitous exoticism, Delacroix instead sought to paint the feline’s timeless beauty in a landscape of wild and eternal grandeur.’

The Delacroix scholar Lee Johnson has noted of the present pastel that ‘Being signed, it seems unlikely to have been made as a study for the [Louvre] painting. With no clue to the pastel’s date in the early sources, it is impossible to be sure which came first; but the pastel, being of a more compact design, with the tail curling around the hindquarters instead of snaking back into the landscape, may well follow closely from the canvas.’

Although Delacroix’s work in pastel accounts for only a very small percentage of his output as a draughtsman, he made use of the medium throughout his career, from the 1820s to the 1860s. As Lee Johnson has noted of the artist, ‘he produced an impressive variety of textural and chromatic effects in exploiting pastel for his own creative ends. It is impossible to calculate precisely how many pastel studies he made…But he seems to have produced roughly one hundred pastels in various states of finish, out of thousands of drawings in other media.’ Delacroix never seems to have exhibited his pastels and appears to have regarded them as private works, to be kept in the studio or presented to particular friends, and sometimes sold to collectors. As Johnson points out, ‘it seems probable that for Delacroix drawing in pastel was mainly a private activity and not practiced for public consumption or financial profit. Pastels made the most attractive and pleasing gifts…’ Among stylistically comparable pastels is a study of a tiger licking its paw, executed in 1850 and smaller in scale, in the collection of the Musée Bonnat-Helleu in Bayonne.

The first owner of the present sheet was the French journalist, art critic and collector Philippe Burty (1830-1890), who assembled a collection of Delacroix’s drawings and prints, as well as notebooks and letters. Although he may not have known the painter very intimately, having only met him once or twice, Burty seems to have rated his work above all other French artists of the period. As one scholar has noted of the writer and critic, ‘one artist dominated his career: Eugène Delacroix…Burty was essentially a late romantic who harbored deep feelings for this artist’s thoughts and paintings throughout his career. Delacroix became the center around whom Burty constructed his pantheon of contemporary painters…In championing Delacroix’s works and writings, Burty passed the romantic painter’s ideas onto a younger generation.’ Burty was one of several scholars tasked with cataloguing the several thousand drawings in Delacroix’s studio after his death, as stipulated in the artist’s will, and wrote the preface to the catalogue of the auction of the contents of the studio in February 1864. He was also the editor of the first edition of Delacroix’s letters, first published in 1878 and in an expanded edition two years later.

Burty consigned this pastel by Delacroix to the Japanese art dealer Hayashi Tadamasa (1853-1906), who had settled in Paris in 1878 and there established a career as a dealer in Japanese prints. The present sheet appears, as ‘Tigre prêt à bondir, pastel’ on the third page of a handwritten contract drawn up between Burty and Tadamasa, dated 13 January 1887, as one of fourteen French paintings from Burty’s collection that Tadamasa was to try and sell for him on a forthcoming trip to New York. By late February 1887 this Delacroix pastel appears to have been acquired from Tadamasa by the celebrated New York collectors Henry O. (1847-1907) and Louisine Havemeyer (1855-1929).

A few years later, around 1894, the Havemeyers consigned Tiger Preparing to Pounce to the Durand-Ruel & Sons Gallery in New York, who eventually purchased the work outright from them in 1898. The present sheet was retained in the private collection of Joseph Durand-Ruel (1862-1928), the son of Paul Durand-Ruel. At the time of his death a brief obituary in the New York Times noted that ‘The private collection of the son [of Paul Durand-Ruel] who has just died is said to be one of the most important in the world.’ The present sheet passed by descent to Joseph’s daughter Marie-Louise Durand-Ruel (1897-1991) and her husband Jean d’Alayer de Costemore d’Arc (1895-1985), and was sold by them at auction in Paris in 1954.

As the scholar Vincent Pomarède has noted, from 1840 ‘Delacroix tried his hand at a new genre, a sort of pictorial transposition of Barye’s animal sculptures enhanced by his imagination and his personal technical concerns…his aesthetic intentions [were] to render the animals’ physical demeanor, to paint their coats using bright and lively colors, to enliven compositions with anecdotal material – creating a serene effect when the feline is resting and a violent one when it is shown devouring its prey – and to blend the depiction of the animal into a richly elaborated landscape. The quantity and quality of these animal scenes made after 1850 indicate that they had become a veritable obsession – a consequence, undoubtedly, of Delacroix’s aesthetic motivations during the final phase of his career…’ As another scholar has written, ‘Delacroix’s animal drawings range from synoptic studies to more finished renderings...He was responsive to the full range of feline behavior, from the almost humanly affectionate interaction of a lioness playing with her cubs...to the predatory beast stalking and attacking its prey.’

A closely related small painting of a Lioness Ready to Spring, signed and dated 1863, is in the Louvre. The pose of the lioness in the painting, which was completed shortly before the artist’s death, differs from that of the tiger in the present pastel mainly in the position of the creature’s tail. As has been noted, the Louvre painting ‘distills the essence of [Delacroix’s] animal studies…He sought a perfect synthesis between an austere treatment of the landscape…and the quiet power of the feline poised to spring. Simply and effectively, he depicted the animal’s physical stance, combining its power and agility with the beauty of its coat, over which his brush lingered without becoming mired in anatomical details…Purposefully eschewing gratuitous exoticism, Delacroix instead sought to paint the feline’s timeless beauty in a landscape of wild and eternal grandeur.’

The Delacroix scholar Lee Johnson has noted of the present pastel that ‘Being signed, it seems unlikely to have been made as a study for the [Louvre] painting. With no clue to the pastel’s date in the early sources, it is impossible to be sure which came first; but the pastel, being of a more compact design, with the tail curling around the hindquarters instead of snaking back into the landscape, may well follow closely from the canvas.’

Although Delacroix’s work in pastel accounts for only a very small percentage of his output as a draughtsman, he made use of the medium throughout his career, from the 1820s to the 1860s. As Lee Johnson has noted of the artist, ‘he produced an impressive variety of textural and chromatic effects in exploiting pastel for his own creative ends. It is impossible to calculate precisely how many pastel studies he made…But he seems to have produced roughly one hundred pastels in various states of finish, out of thousands of drawings in other media.’ Delacroix never seems to have exhibited his pastels and appears to have regarded them as private works, to be kept in the studio or presented to particular friends, and sometimes sold to collectors. As Johnson points out, ‘it seems probable that for Delacroix drawing in pastel was mainly a private activity and not practiced for public consumption or financial profit. Pastels made the most attractive and pleasing gifts…’ Among stylistically comparable pastels is a study of a tiger licking its paw, executed in 1850 and smaller in scale, in the collection of the Musée Bonnat-Helleu in Bayonne.

The first owner of the present sheet was the French journalist, art critic and collector Philippe Burty (1830-1890), who assembled a collection of Delacroix’s drawings and prints, as well as notebooks and letters. Although he may not have known the painter very intimately, having only met him once or twice, Burty seems to have rated his work above all other French artists of the period. As one scholar has noted of the writer and critic, ‘one artist dominated his career: Eugène Delacroix…Burty was essentially a late romantic who harbored deep feelings for this artist’s thoughts and paintings throughout his career. Delacroix became the center around whom Burty constructed his pantheon of contemporary painters…In championing Delacroix’s works and writings, Burty passed the romantic painter’s ideas onto a younger generation.’ Burty was one of several scholars tasked with cataloguing the several thousand drawings in Delacroix’s studio after his death, as stipulated in the artist’s will, and wrote the preface to the catalogue of the auction of the contents of the studio in February 1864. He was also the editor of the first edition of Delacroix’s letters, first published in 1878 and in an expanded edition two years later.

Burty consigned this pastel by Delacroix to the Japanese art dealer Hayashi Tadamasa (1853-1906), who had settled in Paris in 1878 and there established a career as a dealer in Japanese prints. The present sheet appears, as ‘Tigre prêt à bondir, pastel’ on the third page of a handwritten contract drawn up between Burty and Tadamasa, dated 13 January 1887, as one of fourteen French paintings from Burty’s collection that Tadamasa was to try and sell for him on a forthcoming trip to New York. By late February 1887 this Delacroix pastel appears to have been acquired from Tadamasa by the celebrated New York collectors Henry O. (1847-1907) and Louisine Havemeyer (1855-1929).

A few years later, around 1894, the Havemeyers consigned Tiger Preparing to Pounce to the Durand-Ruel & Sons Gallery in New York, who eventually purchased the work outright from them in 1898. The present sheet was retained in the private collection of Joseph Durand-Ruel (1862-1928), the son of Paul Durand-Ruel. At the time of his death a brief obituary in the New York Times noted that ‘The private collection of the son [of Paul Durand-Ruel] who has just died is said to be one of the most important in the world.’ The present sheet passed by descent to Joseph’s daughter Marie-Louise Durand-Ruel (1897-1991) and her husband Jean d’Alayer de Costemore d’Arc (1895-1985), and was sold by them at auction in Paris in 1954.

Eugène Delacroix has long been recognized as one of the finest draughtsmen of the 19th century in France. Adept in a variety of techniques – notably pen, pencil, watercolour, charcoal and pastel - he produced a large and diverse number of drawings of all types. As a modern scholar has noted, ‘For their number, variety and importance he attached to them, drawings are an essential, if not fundamental part of Delacroix’s oeuvre…they represent the most faithful testimonies of the man and the artist with his foibles but his greatness as well.’

However, Delacroix’s output as a draughtsman remained almost completely unknown and unseen by scholars, collectors and connoisseurs until the posthumous auction of the contents of his studio held in February 1864, six months after the artist’s death, which included some six thousand drawings in 430 lots. The sale included not only preparatory compositional sketches and figure studies for Delacroix’s paintings and public commissions, but a myriad variety of drawings by the artist, including studies of wild animals, landscapes, copies after the work of earlier masters, costume studies, scenes from literature, still life subjects and the occasional portrait, as well as finished pastels. In the words of the Delacroix scholar Lee Johnson, ‘It came as a surprise to many that an artist who had been so consistently criticized throughout his career for incompetence as a draughtsman and laxity in composition was revealed by the many hundreds of graphic works, the fifty-five sketchbooks, and scores of oil sketches at his sale to have been a draughtsman of extraordinary versatility and one who went to infinite pains to elaborate the compositions of his paintings through preliminary studies of many kinds, from the inchoate scribbles of an idea in germ, to more articulate designs, to detailed drawings of pose and gesture.’

The largest single collection of drawings by Delacroix, numbering almost three thousand individual sheets and twenty-three sketchbooks, is today in the Louvre.

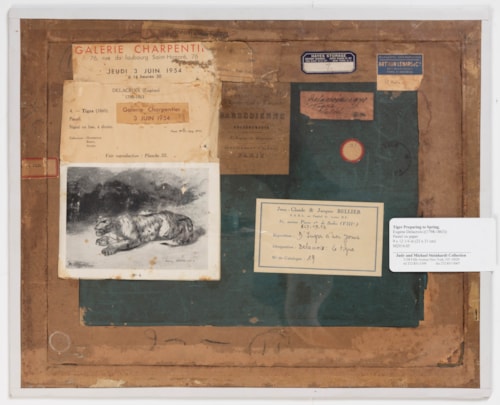

Provenance

Philippe Burty, Paris

Consigned by him to Hayashi Tadamasa, Paris

Acquired from him in 1887 by Henry and Louisine Havemeyer, New York

Purchased from them in March 1898 by the Galerie Durand-Ruel, New York and Paris

Joseph Durand-Ruel, Paris

By descent to his daughter Marie-Louise Durand-Ruel and her husband Jean d’Alayer de Costemore d’Arc

Their sale, Paris, Galerie Charpentier, 3 June 1954, lot 4

Anonymous sale, Paris, Hôtel Drouot [Bellier], 20 December 1956 (sold for 700,000 francs)

Jean-Claude and Jacques Bellier, Paris

Acquired from them in April 1960 by Alexander and Elisabeth Lewyt, New York and Sand’s Point, Long Island

By descent from Elisabeth Roulleau Lewyt to a private collector in 2013

Gallery 19C, Westlake, Texas

Private collection, New York, since 2016.

Consigned by him to Hayashi Tadamasa, Paris

Acquired from him in 1887 by Henry and Louisine Havemeyer, New York

Purchased from them in March 1898 by the Galerie Durand-Ruel, New York and Paris

Joseph Durand-Ruel, Paris

By descent to his daughter Marie-Louise Durand-Ruel and her husband Jean d’Alayer de Costemore d’Arc

Their sale, Paris, Galerie Charpentier, 3 June 1954, lot 4

Anonymous sale, Paris, Hôtel Drouot [Bellier], 20 December 1956 (sold for 700,000 francs)

Jean-Claude and Jacques Bellier, Paris

Acquired from them in April 1960 by Alexander and Elisabeth Lewyt, New York and Sand’s Point, Long Island

By descent from Elisabeth Roulleau Lewyt to a private collector in 2013

Gallery 19C, Westlake, Texas

Private collection, New York, since 2016.

Literature

Forbes Watson, ‘Cleveland Museum’s French Exhibition’, The Arts, January 1930, p.329 (illustrated); Raymonde Wilhélem, ‘Les grandes ventes’, Plaisir de France, February 1957, p.59 (illustrated); Eve Twose Kliman, ‘Delacroix’s Lions and Tigers: A Link Between Man and Nature’, The Art Bulletin, September 1982, pp.461-462, fig.33 (incorrectly stated as in the Cleveland Museum of Art); Lee Johnson, The Paintings of Eugène Delacroix: A Critical Catalogue 1832-1863. Vol.III (Movable Pictures and Private Decorations), Oxford, 1989, p.32, under no.209 (incorrectly as in the Cleveland Museum of Art); Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen et al, Splendid Legacy: The Havemeyer Collection, exhibition catalogue, New York, 1993, p.223, p.339, Appendix no.263; Lee Johnson, Delacroix Pastels, New York, 1995, pp.120-121, no.32 (where dated c.1863, and incorrectly stated as in the Cleveland Museum of Art); Arlette Sérullaz et al, Delacroix: The Late Work, exhibition catalogue, Paris and Philadelphia, 1998-1999, p.317, under no.132 (entry by Vincent Pomarède; incorrectly stated as in the Cleveland Museum of Art); Elizabeth Emery, ‘Hayashi Tadamasa in the United States (1887)’, Journal of Japonisme, 2022, pp.30-31, p.37, note 34, illustrated p.39, fig.5.

Exhibition

Cleveland, Cleveland Museum of Art, French Art since 1800, 1929 (lent by Durand-Ruel); Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Museum of Art and School of Industrial Art, The Romanticists and the Realists: 1860, 1934 (lent by Durand-Ruel); Paris, Galerie Jean-Claude & Jacques Bellier, D’Ingres à nos jours: aquarelles, pastels et dessins, 1960, no.19.