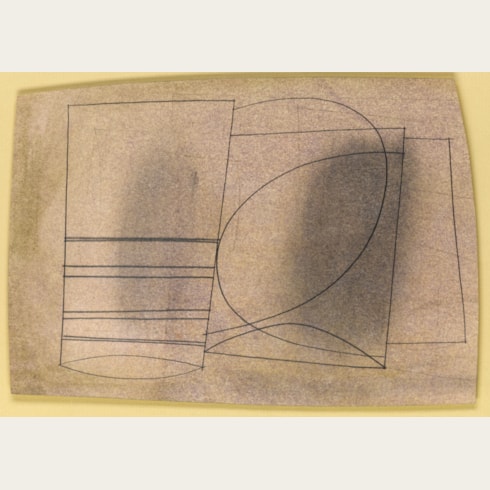

Ben NICHOLSON

(Derham 1894 - London 1982)

Italian Columns (1965)

Pen, ink, watercolour and gouache on paper, laid down on the artist’s prepared etched grey board.

Signed, titled and dated NICHOLSON / 1965 / (Italian columns) on the reverse of the backing board.

248 x 121 mm. (9 3/4 x 4 3/4 in.) [sheet]

317 x 248 mm. (12 1/2 x 9 3/4 in.) [board]

Signed, titled and dated NICHOLSON / 1965 / (Italian columns) on the reverse of the backing board.

248 x 121 mm. (9 3/4 x 4 3/4 in.) [sheet]

317 x 248 mm. (12 1/2 x 9 3/4 in.) [board]

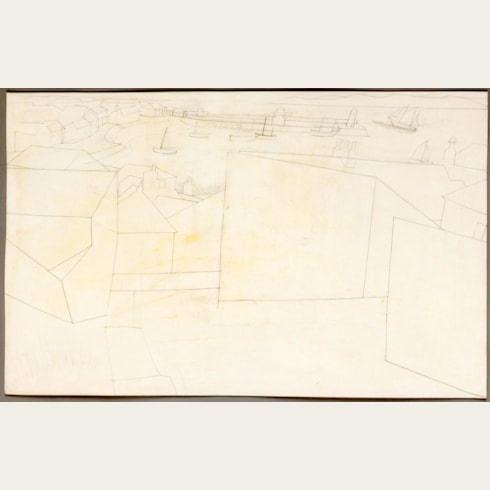

In 1950 Ben Nicholson made his first visit to Italy since the end of the Second World War, and over the next few years began to take a new interest in landscape. He produced a number of drawings of favourite views, sites and buildings throughout the provinces of Tuscany, Lazio and Umbria. As Peter Khoroche has noted of these drawings, ‘He might spend the morning wandering around a town, then be struck by some architectural feature or grouping and feel moved to draw it. Laying no claim to a technical or historical knowledge of architecture, what interested him was the shape, the proportion, the lie of a building – its inner essence or personality would speak of an idea for a free variation upon it. Buildings, like still life objects, were a starting point only: naturally there was no point in mere imitation. On the contrary, Nicholson realized that he had to dare to be free when creating one work of art out of another. Architecture in landscape offered an opportunity to combine his love of precise structure with his feeling for poetry and acute sensitivity to the spirit of place.’

As the artist’s inscription on the verso notes, this drawing was made in 1965. Nicholson’s Italian drawings reveal his fondness for local architecture and landscape; as the artist’s third wife Felicitas Vogler has written, ‘‘When I draw an Italian cathedral’, says Ben Nicholson, ‘I don’t draw its architecture, but the feeling it gives me.’...I have often observed on our travels how B.N. will sit rapt for an hour or two before his subject, usually motionless, but sometimes walking around it to view it from all angles...His landscapes and architectural drawings...are to my mind distinguished from a very early stage by clarity and the great art of omission. They have a delicacy combined with mastery in their strokes, which seem to become more and more economical with the passage of time. For all their fineness they are often of an almost palpable plasticity.’

In many of his Italian landscape drawings, Nicholson first applied a thin wash of oil paint to the surface of the paper, often well before he began the drawing itself. Peter Khoroche has noted that ‘One sign of the enhanced status of drawing within Nicholson’s work as a whole was his practice, from the late 1940s, of applying a thin wash of oil paint to part of each sheet of paper on which he intended to draw. This he did well in advance, without any idea as yet of the subjects he would choose to draw. Raw umber, raw sienna, turquoise or blue would be diluted with a varying proportion of turps, allowing the white ground of the paper to shine through. Like the prepared ground for a relief or a painting, the colour, shape and position of the oil wash provided a starting-point for work as well as giving the finished drawing more body and individuality. From a sheaf of these prepared sheets he would select whichever seemed appropriate to his idea of the landscape, architecture or still life he was about to draw.’

A gouache drawing of a related composition of the same year, but with a different arrangement of black and red colours, appeared on the art market in London in 2003. Also closely related are a small series of etchings entitled Urbino, produced between 1965 and 1966 in collaboration with the Swiss printmaker François Lafranca, which are among Nicholson’s final efforts at printmaking. Some of these etchings of columns were used as the printed bases of a series of drawings executed in pen and ink and gouache.

As the artist’s inscription on the verso notes, this drawing was made in 1965. Nicholson’s Italian drawings reveal his fondness for local architecture and landscape; as the artist’s third wife Felicitas Vogler has written, ‘‘When I draw an Italian cathedral’, says Ben Nicholson, ‘I don’t draw its architecture, but the feeling it gives me.’...I have often observed on our travels how B.N. will sit rapt for an hour or two before his subject, usually motionless, but sometimes walking around it to view it from all angles...His landscapes and architectural drawings...are to my mind distinguished from a very early stage by clarity and the great art of omission. They have a delicacy combined with mastery in their strokes, which seem to become more and more economical with the passage of time. For all their fineness they are often of an almost palpable plasticity.’

In many of his Italian landscape drawings, Nicholson first applied a thin wash of oil paint to the surface of the paper, often well before he began the drawing itself. Peter Khoroche has noted that ‘One sign of the enhanced status of drawing within Nicholson’s work as a whole was his practice, from the late 1940s, of applying a thin wash of oil paint to part of each sheet of paper on which he intended to draw. This he did well in advance, without any idea as yet of the subjects he would choose to draw. Raw umber, raw sienna, turquoise or blue would be diluted with a varying proportion of turps, allowing the white ground of the paper to shine through. Like the prepared ground for a relief or a painting, the colour, shape and position of the oil wash provided a starting-point for work as well as giving the finished drawing more body and individuality. From a sheaf of these prepared sheets he would select whichever seemed appropriate to his idea of the landscape, architecture or still life he was about to draw.’

A gouache drawing of a related composition of the same year, but with a different arrangement of black and red colours, appeared on the art market in London in 2003. Also closely related are a small series of etchings entitled Urbino, produced between 1965 and 1966 in collaboration with the Swiss printmaker François Lafranca, which are among Nicholson’s final efforts at printmaking. Some of these etchings of columns were used as the printed bases of a series of drawings executed in pen and ink and gouache.

The son of the painters William Nicholson and Mabel Pryde, Ben Nicholson spent a brief period at the Slade School of Art in London but was otherwise without formal artistic training. It was not until 1920 and his marriage to the painter Winifred Dacre that he began to paint seriously, producing mainly still life and landscape paintings throughout the following decade. In 1932 he and his second wife, Barbara Hepworth, traveled to France and there met and befriended Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Constantin Brancusi and Jean Arp, and later Piet Mondrian. It was also at this time, in the 1930’s, that Nicholson began to work in a more Cubist manner, creating paintings and reliefs made up of abstract geometrical forms, and in particular producing a series of carved and painted white reliefs that have become icons of 20th century English modernism. At the outbreak of the Second World War, Nicholson and Hepworth and their children moved to the town of St. Ives in Cornwall, where they became the nucleus of a vibrant artistic community. Nicholson’s reputation grew significantly after the war, and he won several artistic prizes in America and elsewhere. In 1954 a retrospective exhibition of his work was held in the British pavilion at the Venice Biennale, followed a year later by one at the Tate. In 1958 he left St. Ives and settled in Switzerland, having annulled his marriage to Hepworth in 1951 and remarried. A second Tate retrospective in 1968 was accompanied by the awarding of the Order of Merit.

Drawing was an important part of Nicholson’s artistic process throughout his career. His drawings were, however, not made as studies for carved reliefs or paintings, and it should be noted that ‘more than simply preparatory or exploratory tools, drawings were to him full-blown works of art…His drawings are characterized by a strong continuous line, which sinuously defines form and space without a break. Shading is used sparingly and any illusion of volumetric mass simply suggested by the interweaving lines.’

Provenance

Galerie Beyeler, Basel

Private collection

Galerie Eric Coatalem, Paris

Private collection, France.

Private collection

Galerie Eric Coatalem, Paris

Private collection, France.