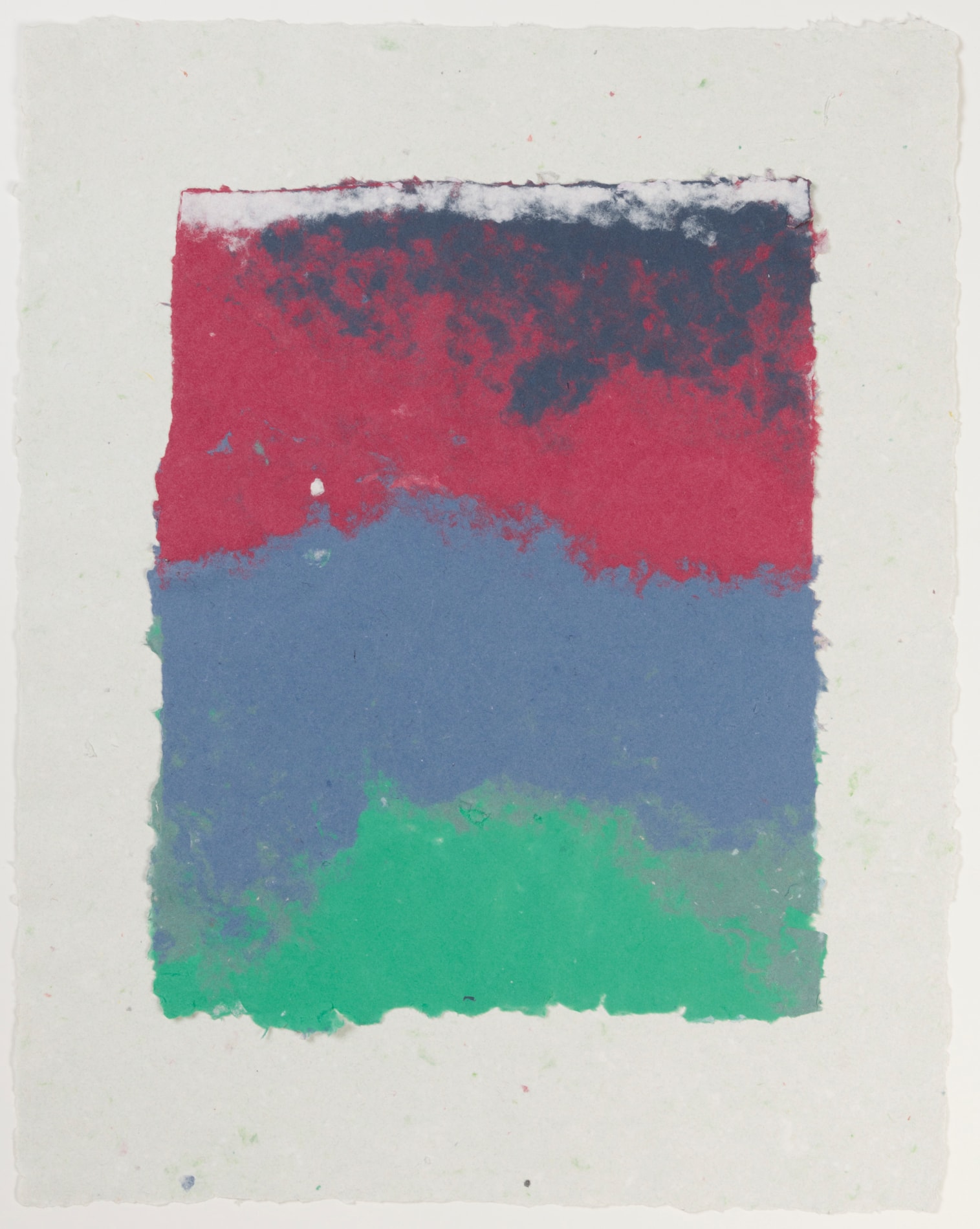

Kenneth NOLAND

(Asheville 1924 - Port Clyde 2010)

Untitled, 1980

Dyed, pressed paper pulp on handmade paper.

Stamped with a drystamp KN near the lower right.

Signed and dated Kenneth Noland / 1980 on the verso.

Numbered PK-0171-2 in pencil on the verso.

444 x 305 mm. (17 1/2 x 12 in.) [image]

626 x 490 mm. (24 5/8 x 19 1/4 in.) [sheet]

Stamped with a drystamp KN near the lower right.

Signed and dated Kenneth Noland / 1980 on the verso.

Numbered PK-0171-2 in pencil on the verso.

444 x 305 mm. (17 1/2 x 12 in.) [image]

626 x 490 mm. (24 5/8 x 19 1/4 in.) [sheet]

The present sheet is one of a distinctive series of works on paper produced by Kenneth Noland beginning in the second half of the 1970s, in a process which he continued to develop for the next two decades. As Judith Goldman has noted, ‘Kenneth Noland created his first handmade paper pieces in 1976. He had not planned to. When he produced a screenprint in 1969, he found printmaking uninteresting. At the time, he was uncomfortable with the collaborative process. Depending on others for results, on master printers and technicians, made him uneasy, and he disliked the idea that prints were reproducible.’

In 1976, however, Noland participated in a Paper Workshop at Bennington College in Vermont, and he soon became interested in papermaking, eventually setting up a paper studio. As Goldman points out, ‘Making paper felt as familiar to Noland as staining color on canvas. It was fast, direct, and not like the traditional print media, a transfer process. He did not have to wait for inks to dry and acids to bite, and he need not depend on anyone else. He could make one-of-a-kind images himself. In some ways, papermaking was more direct than painting. A brush was unnecessary; he could use his hands. Instead of raw canvas, he could begin on a colored ground. To create texture and color, he could overlap pulp, and add colored pulp and cut-up papers ant any point in the process. By embedding color inside the paper, he could define its shape.’

In 1978 Noland spent several months working at Tyler Graphics in Bedford, New York, refining and developing his interest in papermaking, and creating a number of striking works as a result. ‘Working with oriental and western fibres and bits of colored paper, he produced over 200 images. The results were staggering…no two are the same. Colors vary from filmy blues and bright yellows to soft purples and murky greys. Textures range from wafer-thin oriental surfaces to surfaces, thick as encrusted cardboard. In some pieces, image prevails; in some, structure does. Papermaking is never the point; for Noland, it is a way to explore color and create texture.’

The process of using paper pulp as the primary ingredient in this body of work was, in its immediacy and physicality, of great appeal to Noland. The layering of coloured paper pulp to create a final image allowed the artist to explore colour relationships in new ways. Noland’s process in the production of vibrant works in paper pulp, such as the present sheet, has been described at length by Goldman. Writing of the artist’s work at Tyler Graphics in 1978, she noted that, ‘Before each series, and sometimes each image, Noland decides on the base sheet’s color, texture and thickness. He selects fibers to be macerated in the beater, the mould to form paper and the material to color pulp…To form each base sheet, [master printer] Kenneth Tyler and Lindsay Green dip the mould into in the vat, remove and shake it back and forth, so that pulp covers the surface evenly. Then, they turn the mould over, exerting pressure, to transfer the paper to the wet felt on the arched table…While Tyler and Green were creating the base sheet, Noland selected colors in an adjoining room where thirty plastic pails filled with colored pulp covered the floor. There were at least eight different blues, as many greens, every imaginable yellow, grey, fuschia, peach. The array of colors seemed more than sufficient, but from those thirty colors, Noland created 100. Studying the options, Noland moved around the pails. Occasionally, he stopped to mix a new color. To indicate his pleasure, he tossed small buckets into the larger ones which an assistant filled and placed on a small table beside the handmade paper. Noland lined up the pails of color, rearranged them, put handfuls of color in a line on a ledge, looked at the sequence and began...Into [a plastic frame] Noland pushed and patted colored pulp. Using his hands, he sometimes smeared pulp to create a ragged edge or poured water over the pulp, causing color to ooze and blend into the sheet…Noland calls everything he puts into the paper “stuff”, which is the trade name for pulp. The term suggests the sexiness of the material, which can be held in the hand, squeezed and made into shapes. When Noland finishes laying on color, Tyler and Green remove the plastic frame, put the wet sheet between felts and then into the press. The press removes excess water, and fuses the layers of pulp into a continuous surface. The process radically changes the image. Wet pulp looks as glossy and thick as paint; as paper dries, color turns matte, paper and color become inseparable. The color is no longer on top of the paper, but in it.’

As Judith Goldman has also written, ‘Noland’s methods take on interest as they reveal the intelligence and decisions of his art. To the papermaking process, he brought not only an intuitive, extravagant sense of color, but more than thirty years of painting experience…Throughout, he found additional ways to order color. As a painter, that is what he does. Papermaking affords him endless options...Noland brings art to the craft of papermaking. He finds ways to use pulp like paint.’

In 1976, however, Noland participated in a Paper Workshop at Bennington College in Vermont, and he soon became interested in papermaking, eventually setting up a paper studio. As Goldman points out, ‘Making paper felt as familiar to Noland as staining color on canvas. It was fast, direct, and not like the traditional print media, a transfer process. He did not have to wait for inks to dry and acids to bite, and he need not depend on anyone else. He could make one-of-a-kind images himself. In some ways, papermaking was more direct than painting. A brush was unnecessary; he could use his hands. Instead of raw canvas, he could begin on a colored ground. To create texture and color, he could overlap pulp, and add colored pulp and cut-up papers ant any point in the process. By embedding color inside the paper, he could define its shape.’

In 1978 Noland spent several months working at Tyler Graphics in Bedford, New York, refining and developing his interest in papermaking, and creating a number of striking works as a result. ‘Working with oriental and western fibres and bits of colored paper, he produced over 200 images. The results were staggering…no two are the same. Colors vary from filmy blues and bright yellows to soft purples and murky greys. Textures range from wafer-thin oriental surfaces to surfaces, thick as encrusted cardboard. In some pieces, image prevails; in some, structure does. Papermaking is never the point; for Noland, it is a way to explore color and create texture.’

The process of using paper pulp as the primary ingredient in this body of work was, in its immediacy and physicality, of great appeal to Noland. The layering of coloured paper pulp to create a final image allowed the artist to explore colour relationships in new ways. Noland’s process in the production of vibrant works in paper pulp, such as the present sheet, has been described at length by Goldman. Writing of the artist’s work at Tyler Graphics in 1978, she noted that, ‘Before each series, and sometimes each image, Noland decides on the base sheet’s color, texture and thickness. He selects fibers to be macerated in the beater, the mould to form paper and the material to color pulp…To form each base sheet, [master printer] Kenneth Tyler and Lindsay Green dip the mould into in the vat, remove and shake it back and forth, so that pulp covers the surface evenly. Then, they turn the mould over, exerting pressure, to transfer the paper to the wet felt on the arched table…While Tyler and Green were creating the base sheet, Noland selected colors in an adjoining room where thirty plastic pails filled with colored pulp covered the floor. There were at least eight different blues, as many greens, every imaginable yellow, grey, fuschia, peach. The array of colors seemed more than sufficient, but from those thirty colors, Noland created 100. Studying the options, Noland moved around the pails. Occasionally, he stopped to mix a new color. To indicate his pleasure, he tossed small buckets into the larger ones which an assistant filled and placed on a small table beside the handmade paper. Noland lined up the pails of color, rearranged them, put handfuls of color in a line on a ledge, looked at the sequence and began...Into [a plastic frame] Noland pushed and patted colored pulp. Using his hands, he sometimes smeared pulp to create a ragged edge or poured water over the pulp, causing color to ooze and blend into the sheet…Noland calls everything he puts into the paper “stuff”, which is the trade name for pulp. The term suggests the sexiness of the material, which can be held in the hand, squeezed and made into shapes. When Noland finishes laying on color, Tyler and Green remove the plastic frame, put the wet sheet between felts and then into the press. The press removes excess water, and fuses the layers of pulp into a continuous surface. The process radically changes the image. Wet pulp looks as glossy and thick as paint; as paper dries, color turns matte, paper and color become inseparable. The color is no longer on top of the paper, but in it.’

As Judith Goldman has also written, ‘Noland’s methods take on interest as they reveal the intelligence and decisions of his art. To the papermaking process, he brought not only an intuitive, extravagant sense of color, but more than thirty years of painting experience…Throughout, he found additional ways to order color. As a painter, that is what he does. Papermaking affords him endless options...Noland brings art to the craft of papermaking. He finds ways to use pulp like paint.’

After serving in the U.S. Air Force during the Second World War, Kenneth Noland studied at Black Mountain College in North Carolina on the G. I. Bill, which also allowed him to travel to Paris in 1948. There he studied with Ossip Zadkine and was exposed to the work of Picasso, Matisse and Miro, and he also had his first one-man show at the Galerie Raymond Creuze. On his return to America Noland taught at Catholic University in Washington, D.C., and met the older artist Morris Louis, who became a close friend. In 1953 Louis and Noland paid a visit to Helen Frankenthaler’s New York studio, and influenced by her technique of pouring thinned paint onto unprimed canvases, became pioneers of colour-field abstract painting in Washington. Included in a number of important group shows in the mid-1950s, Noland had his first solo exhibition at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York in 1957. The importance of his work was emphasized by his inclusion in the seminal 1964 exhibition Post-Painterly Abstraction, curated by Clement Greenberg, which firmly established the colour field movement as a significant development in American abstraction. Also in 1964, Noland was one of several artists chosen for the American pavilion at the Venice Biennale, along with Morris Louis, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, Claes Oldenburg, and several others.

In 1977 a major travelling retrospective exhibition of Noland’s work was organized by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. As the New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer noted of the exhibition, ‘Mr. Noland is one of the artists who have decisively shaped American painting - or at least some very important elements of it - over the last 20 years...no matter what the size or shape of his pictures, Mr. Noland has been consistent and unvarying - not to say single‐minded - in his artistic purpose, which has been to fill the canvas surface with a pictorial experience of pure color…An art of this sort places a very heavy burden on the artist’s sensibility for color, of course - on his ability to come up, again and again, with fresh and striking combinations that both capture and sustain our attention, and provide the requisite pleasure. In this respect, at least, Mr. Noland is unquestionably a master.’

Noland may indeed be regarded as one of the great colourists of the 20th century. His method involved staining the canvas with colour, rather than using a brush. Working on a large scale, he produced canvases characterized by simple patterns of chevrons, stripes, and concentric circles or targets painted in bold blocks of colour, as well as shaped canvases, which became asymmetrical in the 1970s and 1980s. Admired for his significant contribution to American abstraction, Noland’s works are found in numerous international museums.

In 1977 a major travelling retrospective exhibition of Noland’s work was organized by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. As the New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer noted of the exhibition, ‘Mr. Noland is one of the artists who have decisively shaped American painting - or at least some very important elements of it - over the last 20 years...no matter what the size or shape of his pictures, Mr. Noland has been consistent and unvarying - not to say single‐minded - in his artistic purpose, which has been to fill the canvas surface with a pictorial experience of pure color…An art of this sort places a very heavy burden on the artist’s sensibility for color, of course - on his ability to come up, again and again, with fresh and striking combinations that both capture and sustain our attention, and provide the requisite pleasure. In this respect, at least, Mr. Noland is unquestionably a master.’

Noland may indeed be regarded as one of the great colourists of the 20th century. His method involved staining the canvas with colour, rather than using a brush. Working on a large scale, he produced canvases characterized by simple patterns of chevrons, stripes, and concentric circles or targets painted in bold blocks of colour, as well as shaped canvases, which became asymmetrical in the 1970s and 1980s. Admired for his significant contribution to American abstraction, Noland’s works are found in numerous international museums.

Provenance

Galerie Thierry Salvador, Paris

Anonymous sale, Versailles, Versailles Enchères, 14 December 2014, lot 110

Private collection, France.

Anonymous sale, Versailles, Versailles Enchères, 14 December 2014, lot 110

Private collection, France.