Dora MAAR

(Paris 1907 - Paris 1997)

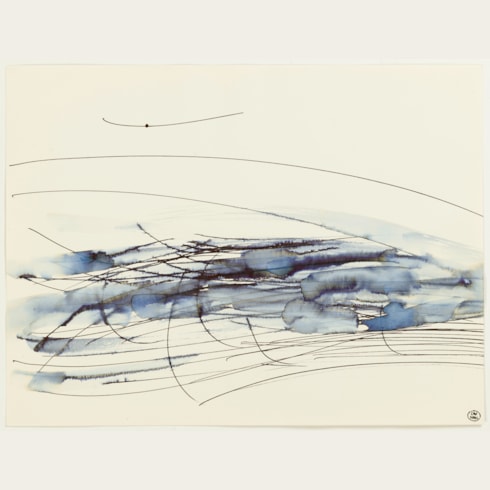

Untitled

Sold

Brush, oil and purple and green washes on white paper.

Inscribed DT. in purple ink on the verso.

210 x 270 mm. (8 1/4 x 10 5/8 in.)

Inscribed DT. in purple ink on the verso.

210 x 270 mm. (8 1/4 x 10 5/8 in.)

This drawing may be grouped with a series of bold, abstract compositions, executed in either watercolour, gouache, thinned oil paint, ballpoint, ink and wash and felt-tip pen, that Dora Maar drew from the 1960s onwards, almost all of which were never seen or exhibited in her lifetime. Parallels may be found among the painted landscapes on canvas that she produced in the 1950s, although the works on paper are more spontaneous in execution. The artist, who left almost no writings or letters about her work, rarely signed her drawings, and an accurate dating of them remains problematic.

In a letter to Maar published as the introduction to the catalogue of an exhibition of her landscape paintings and watercolours at the Berggruen gallery in Paris in 1957, the English scholar and critic Douglas Cooper wrote, ‘How much progress, of change of spirit, separates your landscapes of today from your painting before the war...I will speak only for myself, but I would like you to know that what I like the most about your recent paintings is the direct inspiration from nature, it is a spontaneous and not at all forced romantic spirit, and above all it is the fine craftsmanship of the painter which they show. Dare I confess to you, without insisting too much, that I see in them, on the one hand, a relationship with Turner, and on the other, a rapport with Courbet?...You have a real vision as a painter, you have the courage to pursue this vision until it is realized on the canvas, and you are above all well served by a skilful hand, by a remarkable manner of handling of paint, a sensibility and an instinct which is very sure.’

This drawing was acquired at the 1999 Maar sale by the jewellery designer and artist Dominique de Roquemaurel-Galitzine, who purchased three boxes of unmounted drawings, numbering over 160 sheets. For around twenty years these drawings remained untouched in their cardboard boxes, stored by de Roquemaurel-Galitzine on top of a cupboard, although a few sheets from her collection were included in the Dora Maar exhibitions at the Centre Pompidou and the Tate Modern in 2019.

In a letter to Maar published as the introduction to the catalogue of an exhibition of her landscape paintings and watercolours at the Berggruen gallery in Paris in 1957, the English scholar and critic Douglas Cooper wrote, ‘How much progress, of change of spirit, separates your landscapes of today from your painting before the war...I will speak only for myself, but I would like you to know that what I like the most about your recent paintings is the direct inspiration from nature, it is a spontaneous and not at all forced romantic spirit, and above all it is the fine craftsmanship of the painter which they show. Dare I confess to you, without insisting too much, that I see in them, on the one hand, a relationship with Turner, and on the other, a rapport with Courbet?...You have a real vision as a painter, you have the courage to pursue this vision until it is realized on the canvas, and you are above all well served by a skilful hand, by a remarkable manner of handling of paint, a sensibility and an instinct which is very sure.’

This drawing was acquired at the 1999 Maar sale by the jewellery designer and artist Dominique de Roquemaurel-Galitzine, who purchased three boxes of unmounted drawings, numbering over 160 sheets. For around twenty years these drawings remained untouched in their cardboard boxes, stored by de Roquemaurel-Galitzine on top of a cupboard, although a few sheets from her collection were included in the Dora Maar exhibitions at the Centre Pompidou and the Tate Modern in 2019.

Born Henriette Théodora Markovitch in Paris, the only child of a Croatian father and a French mother, and raised in Argentina until the early 1920s, Dora Maar studied in Paris at the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs and the Académie Julian. In 1927, she also took classes in the studio of the painter André Lhote, where she met the photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, before enrolling in the Ecole Technique de Photographie et de Cinématographie de la Ville de Paris. Initially undecided between pursuing a career as a painter or photographer, she opened a photographic studio, in association with the art director and set designer Pierre Kéfer, in Neuilly-sur-Seine in 1931.

Maar soon established a reputation as a fashion photographer, while also producing photographs of advertising images, architectural and urban views, portraits and nudes; many of these were done on commission for magazines, books, and beauty and fashion companies. In 1932 and 1934 Maar’s photographs were exhibited at galleries in Paris, shortly before her professional relationship with Kéfer ended. In 1935 she met André Breton and began to be involved in the activities of the Surrealists, who admired her sometimes fantastical photomontages in particular. Maar’s work was included in several Surrealist publications and exhibitions in the mid to late 1930s, while among her circle of friends in Paris were the female Surrealists Nusch Eluard and Jacqueline Lamba, as well as the American photojournalist Lee Miller.

Dora Maar is said to have encountered Pablo Picasso at the café Les Deux Magots in Paris in January 1936, and the two soon began an intense relationship. She first appears in Picasso’s paintings in the summer of that year, while sharing the artist’s company at Mougins in the South of France. She was to be Picasso’s mistress and muse for nine years, between 1936 and 1943; through the period of the Spanish Civil War, the outbreak of World War II and the Occupation of Paris. Picasso painted numerous portraits of Maar, most famously as an anguished, weeping woman in a series of paintings executed throughout 1937. Maar was the only photographer allowed access to Picasso’s studio as he was painting the massive Guernica in May and June of 1937, and produced dozens of photographs of the master at work on the large mural that have become an important resource for scholars documenting the genesis of this seminal work. She also taught Picasso basic photographic techniques, and they collaborated on some experimental works, a number of of which were published in the magazine Cahiers d’Art in 1937. Maar eventually gave up photography and, encouraged by Picasso, turned to painting. Together with another artist, she had an exhibition of her work in Paris in June 1944, while her first solo show took place at the Pierre Loeb Gallery two years later. This was, however, to be the last time her work was seen in public for over a decade.

Maar’s relationship with Picasso ended after the war, following the introduction into his life of his new lover, the young painter Françoise Gilot. She started to suffer from depression, enduring a nervous breakdown that led to a stay in hospital, as well as treatment by the renowned psychiatrist Jacques Lacan. At about the same time, around 1946, she stopped exhibiting her work. She continued to paint, however, and began to focus on a series of increasingly reductive landscapes inspired by the area around the Provençal town of Ménerbes, where she spent her summers. It has been suggested that the growing focus on abstraction in these works was an attempt to free herself of the pervasive stylistic influence of Picasso, whose work was always rooted in representation.

The last forty years of Maar’s life were spent largely as a recluse, living between her apartment on the rue de Savoie in Paris and a large house in Ménerbes, which Picasso had helped her to buy in 1945. She saw very few people, allowed almost no one into her home or studio, and devoted herself mainly to painting brooding Provençal landscapes devoid of figures. Despite her isolation, throughout the 1950s she continued to maintain friendships with artists and writers such as Balthus, André du Bouchet, Marc Chagall, Nicolas de Staël (who was a neighbour in Ménerbes), Paul Eluard, André Masson and Man Ray, as well as collectors like Douglas Cooper and Marie-Laure de Noailles. Among the very few visitors to her studio whom she allowed to see her work was her friend, the American writer James Lord, who stayed at Ménerbes in the spring and summer of 1954. Despite her almost ascetic removal from the art world, however, Maar never faltered in her belief that her talent would one day be recognized. As she once told Lord, ‘I must dwell apart in the desert. I want to create an aura of mystery about my work. People must long to see it. I’m still too famous as Picasso’s mistress to be accepted as a painter.’

For many years, Maar, who did not drive, would travel on a motorcycle around the mountainous valley of the Luberon region near Ménerbes, sketching the landscape. (As Lord recalled, ‘Dora riding out on her motorbike to make watercolors in the countryside, I thought, looked rather ludicrous, her hair done up in a woolen scarf and with a sack slung over her shoulders, decidedly too old for that kind of conveyance.’) Some of Maar’s landscape paintings, many verging on abstraction, were shown in two separate exhibitions at a gallery in Paris in 1957 and another in London in 1958. Of the first of these shows, one writer noted that the artist ‘succeeds admirably in catching the savage beauty of this corner of France’, while writing of the second, the critic John Russell described the works as ‘a hermit’s paintings’ and Maar as ‘an attentive student of nature, in whose work a fondness for plunging perspectives and great trailing scarves of color was kept in check by the finest regard for the structure of the scene before her.’

By the early 1970s, Maar’s paintings and drawings had become completely abstractive, characterized by experimental techniques and a bold use of various media. Living in seclusion, either in Paris or the dilapidated, unheated house in Ménerbes, she saw almost no one and, deeply religious, spent much of her time in prayer, and also wrote poetry. Nevertheless, she continued to work productively as an artist, with characteristic rigour and determination, until the end of her life. (Although she generally refused to have her paintings or works on paper exhibited, or to be illustrated in books or catalogues, in 1990 she allowed the dealer Marcel Fleiss of the Galerie 1900-2000 in Paris to show some of her landscapes and still-lifes.) An exhibition of paintings and photographs in Valencia in 1995 was the only significant museum show of her oeuvre to take place in her lifetime; the exhibition was meant to travel to the Centre Pompidou in Paris but was eventually cancelled due to the artist’s unhappiness with it. Almost completely forgotten by the world at large, Dora Maar died in 1997, at the age of eighty-nine.

At the time of her death, Maar left no will, and had no known heirs. She owned numerous works by Picasso, all given to her by the artist, and although she had sold a number of these towards the end of her life in order to have money to live, the vast majority of her collection remained in her possession. The contents of her homes in Paris and Ménerbes, including works by Picasso, were conservatively valued at 150 million francs after her death, and were dispersed in a series of auctions in Paris in 1998 and 1999. (The first two sales alone, comprised of paintings, drawings and objects by Picasso, realized a total of 213 million francs). Some twenty-two years after Maar’s death a major retrospective exhibition devoted to her work was held at the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Tate Modern in London.

Maar soon established a reputation as a fashion photographer, while also producing photographs of advertising images, architectural and urban views, portraits and nudes; many of these were done on commission for magazines, books, and beauty and fashion companies. In 1932 and 1934 Maar’s photographs were exhibited at galleries in Paris, shortly before her professional relationship with Kéfer ended. In 1935 she met André Breton and began to be involved in the activities of the Surrealists, who admired her sometimes fantastical photomontages in particular. Maar’s work was included in several Surrealist publications and exhibitions in the mid to late 1930s, while among her circle of friends in Paris were the female Surrealists Nusch Eluard and Jacqueline Lamba, as well as the American photojournalist Lee Miller.

Dora Maar is said to have encountered Pablo Picasso at the café Les Deux Magots in Paris in January 1936, and the two soon began an intense relationship. She first appears in Picasso’s paintings in the summer of that year, while sharing the artist’s company at Mougins in the South of France. She was to be Picasso’s mistress and muse for nine years, between 1936 and 1943; through the period of the Spanish Civil War, the outbreak of World War II and the Occupation of Paris. Picasso painted numerous portraits of Maar, most famously as an anguished, weeping woman in a series of paintings executed throughout 1937. Maar was the only photographer allowed access to Picasso’s studio as he was painting the massive Guernica in May and June of 1937, and produced dozens of photographs of the master at work on the large mural that have become an important resource for scholars documenting the genesis of this seminal work. She also taught Picasso basic photographic techniques, and they collaborated on some experimental works, a number of of which were published in the magazine Cahiers d’Art in 1937. Maar eventually gave up photography and, encouraged by Picasso, turned to painting. Together with another artist, she had an exhibition of her work in Paris in June 1944, while her first solo show took place at the Pierre Loeb Gallery two years later. This was, however, to be the last time her work was seen in public for over a decade.

Maar’s relationship with Picasso ended after the war, following the introduction into his life of his new lover, the young painter Françoise Gilot. She started to suffer from depression, enduring a nervous breakdown that led to a stay in hospital, as well as treatment by the renowned psychiatrist Jacques Lacan. At about the same time, around 1946, she stopped exhibiting her work. She continued to paint, however, and began to focus on a series of increasingly reductive landscapes inspired by the area around the Provençal town of Ménerbes, where she spent her summers. It has been suggested that the growing focus on abstraction in these works was an attempt to free herself of the pervasive stylistic influence of Picasso, whose work was always rooted in representation.

The last forty years of Maar’s life were spent largely as a recluse, living between her apartment on the rue de Savoie in Paris and a large house in Ménerbes, which Picasso had helped her to buy in 1945. She saw very few people, allowed almost no one into her home or studio, and devoted herself mainly to painting brooding Provençal landscapes devoid of figures. Despite her isolation, throughout the 1950s she continued to maintain friendships with artists and writers such as Balthus, André du Bouchet, Marc Chagall, Nicolas de Staël (who was a neighbour in Ménerbes), Paul Eluard, André Masson and Man Ray, as well as collectors like Douglas Cooper and Marie-Laure de Noailles. Among the very few visitors to her studio whom she allowed to see her work was her friend, the American writer James Lord, who stayed at Ménerbes in the spring and summer of 1954. Despite her almost ascetic removal from the art world, however, Maar never faltered in her belief that her talent would one day be recognized. As she once told Lord, ‘I must dwell apart in the desert. I want to create an aura of mystery about my work. People must long to see it. I’m still too famous as Picasso’s mistress to be accepted as a painter.’

For many years, Maar, who did not drive, would travel on a motorcycle around the mountainous valley of the Luberon region near Ménerbes, sketching the landscape. (As Lord recalled, ‘Dora riding out on her motorbike to make watercolors in the countryside, I thought, looked rather ludicrous, her hair done up in a woolen scarf and with a sack slung over her shoulders, decidedly too old for that kind of conveyance.’) Some of Maar’s landscape paintings, many verging on abstraction, were shown in two separate exhibitions at a gallery in Paris in 1957 and another in London in 1958. Of the first of these shows, one writer noted that the artist ‘succeeds admirably in catching the savage beauty of this corner of France’, while writing of the second, the critic John Russell described the works as ‘a hermit’s paintings’ and Maar as ‘an attentive student of nature, in whose work a fondness for plunging perspectives and great trailing scarves of color was kept in check by the finest regard for the structure of the scene before her.’

By the early 1970s, Maar’s paintings and drawings had become completely abstractive, characterized by experimental techniques and a bold use of various media. Living in seclusion, either in Paris or the dilapidated, unheated house in Ménerbes, she saw almost no one and, deeply religious, spent much of her time in prayer, and also wrote poetry. Nevertheless, she continued to work productively as an artist, with characteristic rigour and determination, until the end of her life. (Although she generally refused to have her paintings or works on paper exhibited, or to be illustrated in books or catalogues, in 1990 she allowed the dealer Marcel Fleiss of the Galerie 1900-2000 in Paris to show some of her landscapes and still-lifes.) An exhibition of paintings and photographs in Valencia in 1995 was the only significant museum show of her oeuvre to take place in her lifetime; the exhibition was meant to travel to the Centre Pompidou in Paris but was eventually cancelled due to the artist’s unhappiness with it. Almost completely forgotten by the world at large, Dora Maar died in 1997, at the age of eighty-nine.

At the time of her death, Maar left no will, and had no known heirs. She owned numerous works by Picasso, all given to her by the artist, and although she had sold a number of these towards the end of her life in order to have money to live, the vast majority of her collection remained in her possession. The contents of her homes in Paris and Ménerbes, including works by Picasso, were conservatively valued at 150 million francs after her death, and were dispersed in a series of auctions in Paris in 1998 and 1999. (The first two sales alone, comprised of paintings, drawings and objects by Picasso, realized a total of 213 million francs). Some twenty-two years after Maar’s death a major retrospective exhibition devoted to her work was held at the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Tate Modern in London.

Provenance

The estate of the artist, with the studio stamp DM 1998 in an oval (not in Lugt) at the lower right

The posthumous vente Dora Maar, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, 27 May 1999, lot unidentified

Dominique de Roquemaurel-Galitzine, until 2021.

The posthumous vente Dora Maar, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, 27 May 1999, lot unidentified

Dominique de Roquemaurel-Galitzine, until 2021.

Literature

Giulia Pentcheff, Collection Dominique de Roquemaurel-Galitzine. Dora Maar: Seule au bord de la Terre, exhibition catalogue, Marseille, 2022, p.116, no.106.

Exhibition

Marseille, Galerie Alexis Pentcheff, Dora Maar: Seule au bord de la Terre, 2022, no.106.