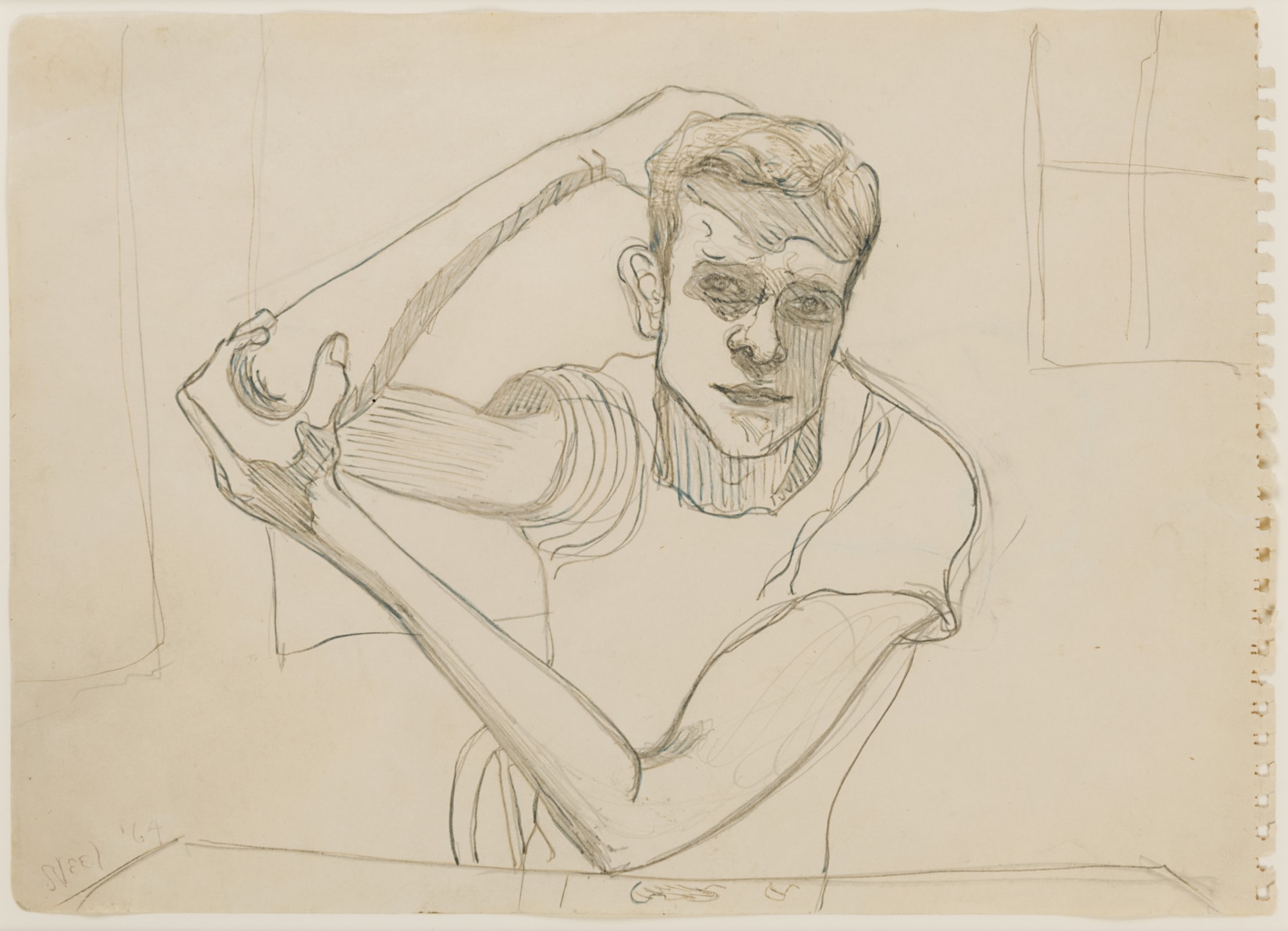

Alice NEEL

(Gladwyne 1900 - New York 1984)

Richard Gibbs

Sold

Pencil and blue and brown ink on paper; a page from a sketchbook.

Signed and dated Neel ’64 at the lower left.

249 x 350 mm. (9 3/4 x 13 3/4 in.)

Signed and dated Neel ’64 at the lower left.

249 x 350 mm. (9 3/4 x 13 3/4 in.)

In general, Alice Neel did not prepare her canvases with preparatory studies on paper, preferring instead to draw with paint directly on the canvas. Nevertheless, drawing played an important role in her artistic practice, the immediacy of the process allowing her to quickly capture a sitter’s pose or a subject seen on the street. As the scholar Jeremy Lewison has noted, ‘the activity of drawing on paper filled the interstices of time; it allowed her to work on other ideas simultaneously, and sometimes more experimentally or casually…It is [the] combination of the detailed and the economical that characterises Neel’s work as both a painter and a draughtsman…Neel’s approach to drawing and painting, if not experimental, is authoritative, distinctive and engaged with a long tradition that she sought to develop rather than overthrow.’

A committed draughtsman, Neel produced a large number of drawings and watercolours. While her relatively few surviving drawings of the 1920s and early 1930s were typically executed in watercolour, by the late 1930s she was working mostly in pencil or black ink, and her drawings remained largely monochromatic, with some exceptions, for the remainder of her career. Neel regarded her drawings not as studies for paintings but as fully independent works. For much of her career, however, her drawings were also very private, intimate works, and not intended to be exhibited in public. In 1978 the first retrospective exhibition of Neel’s works on paper was held at the Graham Gallery, and after the artist’s death further gallery and museum shows devoted solely to her drawings and watercolours followed in 1986, 2003, 2008, 2013 and 2015.

Drawn in 1964, on a page from one of the artist’s sketchbooks, the present sheet depicts Richard Gibbs, about whom very little is known. Neel painted several portraits of Gibbs, including works dated 1961 and 1965, while a very large canvas, executed in 1968, is today in a private collection in Minneapolis. It remains unclear who Gibbs was, however. Neel often painted friends and neighbours, as well as more obscure figures, but nothing further is known of this particular sitter.

In the brochure accompanying the first exhibition devoted solely to drawings by Neel at the Graham Gallery in 1978, the art historian Ann Sutherland Harris wrote of the artist that ‘We realize again that her paintings are full of visible drawing, sketched passages, emphatic contour lines…we are reminded that Neel was trained to draw by the most academic and traditional of methods and that she knows her craft. But her formidable gifts have never been used to describe the surface of life. Her drawings, as much as her paintings, probe for the truth and contribute to her incisive, idiosyncratic but compassionate record of life in America in this century as she had seen it and as she continues to see it.’

A committed draughtsman, Neel produced a large number of drawings and watercolours. While her relatively few surviving drawings of the 1920s and early 1930s were typically executed in watercolour, by the late 1930s she was working mostly in pencil or black ink, and her drawings remained largely monochromatic, with some exceptions, for the remainder of her career. Neel regarded her drawings not as studies for paintings but as fully independent works. For much of her career, however, her drawings were also very private, intimate works, and not intended to be exhibited in public. In 1978 the first retrospective exhibition of Neel’s works on paper was held at the Graham Gallery, and after the artist’s death further gallery and museum shows devoted solely to her drawings and watercolours followed in 1986, 2003, 2008, 2013 and 2015.

Drawn in 1964, on a page from one of the artist’s sketchbooks, the present sheet depicts Richard Gibbs, about whom very little is known. Neel painted several portraits of Gibbs, including works dated 1961 and 1965, while a very large canvas, executed in 1968, is today in a private collection in Minneapolis. It remains unclear who Gibbs was, however. Neel often painted friends and neighbours, as well as more obscure figures, but nothing further is known of this particular sitter.

In the brochure accompanying the first exhibition devoted solely to drawings by Neel at the Graham Gallery in 1978, the art historian Ann Sutherland Harris wrote of the artist that ‘We realize again that her paintings are full of visible drawing, sketched passages, emphatic contour lines…we are reminded that Neel was trained to draw by the most academic and traditional of methods and that she knows her craft. But her formidable gifts have never been used to describe the surface of life. Her drawings, as much as her paintings, probe for the truth and contribute to her incisive, idiosyncratic but compassionate record of life in America in this century as she had seen it and as she continues to see it.’

Although Alice Neel’s career spanned much of the 20th century – she was born three weeks into the new century - it was not until she was already in her late sixties that she began to enjoy critical acclaim, after working for much of her life in relative obscurity. Neel received her artistic training at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, where she studied between 1921 and 1925. She then spent two important and formative years in Havana, where she lived with her husband, the Cuban artist Carlos Enriquez, with whom she had two daughters. Neel participated in a number of exhibitions in Cuba before eventually returning to America and settling in New York City, which was to be her home for the remainder of her life. In 1930 she suffered a nervous breakdown, caused by Enriquez’s abandonment of her and his return to Cuba with their second daughter Isabetta. (Santillana, their first child, had died of diphtheria in 1927.) By early 1932 Neel was living in Greenwich Village, surrounded by a vibrant community of artists, intellectuals and political activists, many of whom sat for her. She exhibited in a number of group shows and had relationships with a series of lovers, all of whom appeared in her work. (One of these, Kenneth Doolittle, in a rage, burned and destroyed over three hundred drawings and some fifty paintings in her studio in 1934.) During these years at the height of the Great Depression, Neel worked for the government’s Public Works of Art Program and later the Federal Art Project, part of the Works Progress Administration, with which she remained associated until it was ended in 1943.

Throughout Neel’s nearly seven-decade career she expressed a particular concern with issues of social justice and civil rights, and much of her work made manifest a kind of radical humanism. A member of the Communist Party since 1935, she was involved with leftist and socialist movements throughout her life. In 1938 Neel had her first solo exhibition at a gallery in New York, and the same year moved uptown to Spanish Harlem. For the next twenty-four years she lived and worked there, in the area of the east side of Manhattan known to its inhabitants as El Barrio, which became the setting for many of her paintings of cityscapes and genre scenes. Her studio was her large living room, and it was there that she painted numerous portraits of her Black and Puerto Rican neighbours, some of which these were included in a solo exhibition at the A.C.A. Gallery in 1950. As a review of the exhibition in the New York Times noted, ‘Her approach is frankly expressionistic; she uses a great deal of black, accentuating profile lines, and catches figures in strongly individual poses. And its dramatic intensity succeeds because of unmistakable artistic sincerity.’ Although Neel’s paintings were occasionally included in group exhibitions and she had further solo exhibitions in 1951, 1954, 1960 and 1962, her work garnered relatively little critical attention until an article on her portraiture was published in Art News in 1962. The following year Neel began to be represented by the Graham Gallery, which mounted several exhibitions of her work between 1963 and 1980.

Neel continued to work mainly as a painter of portraits, one of which was used for the cover of Time magazine in 1970; while the same year she painted one of her best-known works, a striking portrait of Andy Warhol. She regularly gave slide lectures about her work throughout the country; these presentations were always highly entertaining and proved very popular. A long-overdue retrospective exhibition of Neel’s oeuvre, numbering fifty-eight paintings, was mounted at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1974, while another large exhibition of over eighty paintings was held at the Georgia Museum of Art the following year. By the middle of the 1970s Neel was widely recognized, albeit belatedly, as one of most significant figurative painters of the post-war era, and was the recipient of a number of awards and honours. In 1982 she began being represented by the Robert Miller Gallery, and also contributed to the first illustrated monograph of her work, which appeared the year before her death from advanced colon cancer in 1984. Today, Neel’s work is held in countless museums in America and Europe, while in recent years she has been the subject of major museum exhibitions in Bilbao, Edinburgh, The Hague, Hamburg, Helsinki, Houston, London, Malmö, New York, Paris, Stockholm and Washington, D.C.

Alice Neel tended to reject the label of portraitist, preferring to describe her work as ‘pictures of people’. The artist’s biographer Phoebe Hoban has recently written of Neel that ‘Her stated goal was to chronicle the Zeitgeist, and Neel was, from the very start, fiercely democratic in her subjects, portraying her lovers, her children, pregnant nudes, fringe characters, and famous art-world figures. Neel’s art provides a vivid lens with which to view the twentieth century…Few portrait painters besides Lucian Freud have been as unflinching in their gaze. But while Freud is a clinician, his cold dissection of his subjects often chilling, Neel is an avowed humanist, interested not only in her subjects’ physiognomy but in their heart and soul…“That is the microcosm,” she said. “Everything can be there – the person, his position in life, how he feels, how he thinks, what life does to him, how he retaliates, the spirit of the times, everything.”’

Throughout Neel’s nearly seven-decade career she expressed a particular concern with issues of social justice and civil rights, and much of her work made manifest a kind of radical humanism. A member of the Communist Party since 1935, she was involved with leftist and socialist movements throughout her life. In 1938 Neel had her first solo exhibition at a gallery in New York, and the same year moved uptown to Spanish Harlem. For the next twenty-four years she lived and worked there, in the area of the east side of Manhattan known to its inhabitants as El Barrio, which became the setting for many of her paintings of cityscapes and genre scenes. Her studio was her large living room, and it was there that she painted numerous portraits of her Black and Puerto Rican neighbours, some of which these were included in a solo exhibition at the A.C.A. Gallery in 1950. As a review of the exhibition in the New York Times noted, ‘Her approach is frankly expressionistic; she uses a great deal of black, accentuating profile lines, and catches figures in strongly individual poses. And its dramatic intensity succeeds because of unmistakable artistic sincerity.’ Although Neel’s paintings were occasionally included in group exhibitions and she had further solo exhibitions in 1951, 1954, 1960 and 1962, her work garnered relatively little critical attention until an article on her portraiture was published in Art News in 1962. The following year Neel began to be represented by the Graham Gallery, which mounted several exhibitions of her work between 1963 and 1980.

Neel continued to work mainly as a painter of portraits, one of which was used for the cover of Time magazine in 1970; while the same year she painted one of her best-known works, a striking portrait of Andy Warhol. She regularly gave slide lectures about her work throughout the country; these presentations were always highly entertaining and proved very popular. A long-overdue retrospective exhibition of Neel’s oeuvre, numbering fifty-eight paintings, was mounted at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1974, while another large exhibition of over eighty paintings was held at the Georgia Museum of Art the following year. By the middle of the 1970s Neel was widely recognized, albeit belatedly, as one of most significant figurative painters of the post-war era, and was the recipient of a number of awards and honours. In 1982 she began being represented by the Robert Miller Gallery, and also contributed to the first illustrated monograph of her work, which appeared the year before her death from advanced colon cancer in 1984. Today, Neel’s work is held in countless museums in America and Europe, while in recent years she has been the subject of major museum exhibitions in Bilbao, Edinburgh, The Hague, Hamburg, Helsinki, Houston, London, Malmö, New York, Paris, Stockholm and Washington, D.C.

Alice Neel tended to reject the label of portraitist, preferring to describe her work as ‘pictures of people’. The artist’s biographer Phoebe Hoban has recently written of Neel that ‘Her stated goal was to chronicle the Zeitgeist, and Neel was, from the very start, fiercely democratic in her subjects, portraying her lovers, her children, pregnant nudes, fringe characters, and famous art-world figures. Neel’s art provides a vivid lens with which to view the twentieth century…Few portrait painters besides Lucian Freud have been as unflinching in their gaze. But while Freud is a clinician, his cold dissection of his subjects often chilling, Neel is an avowed humanist, interested not only in her subjects’ physiognomy but in their heart and soul…“That is the microcosm,” she said. “Everything can be there – the person, his position in life, how he feels, how he thinks, what life does to him, how he retaliates, the spirit of the times, everything.”’

Provenance

Robert Miller Gallery, New York

Private collection, United Kingdom.

Private collection, United Kingdom.