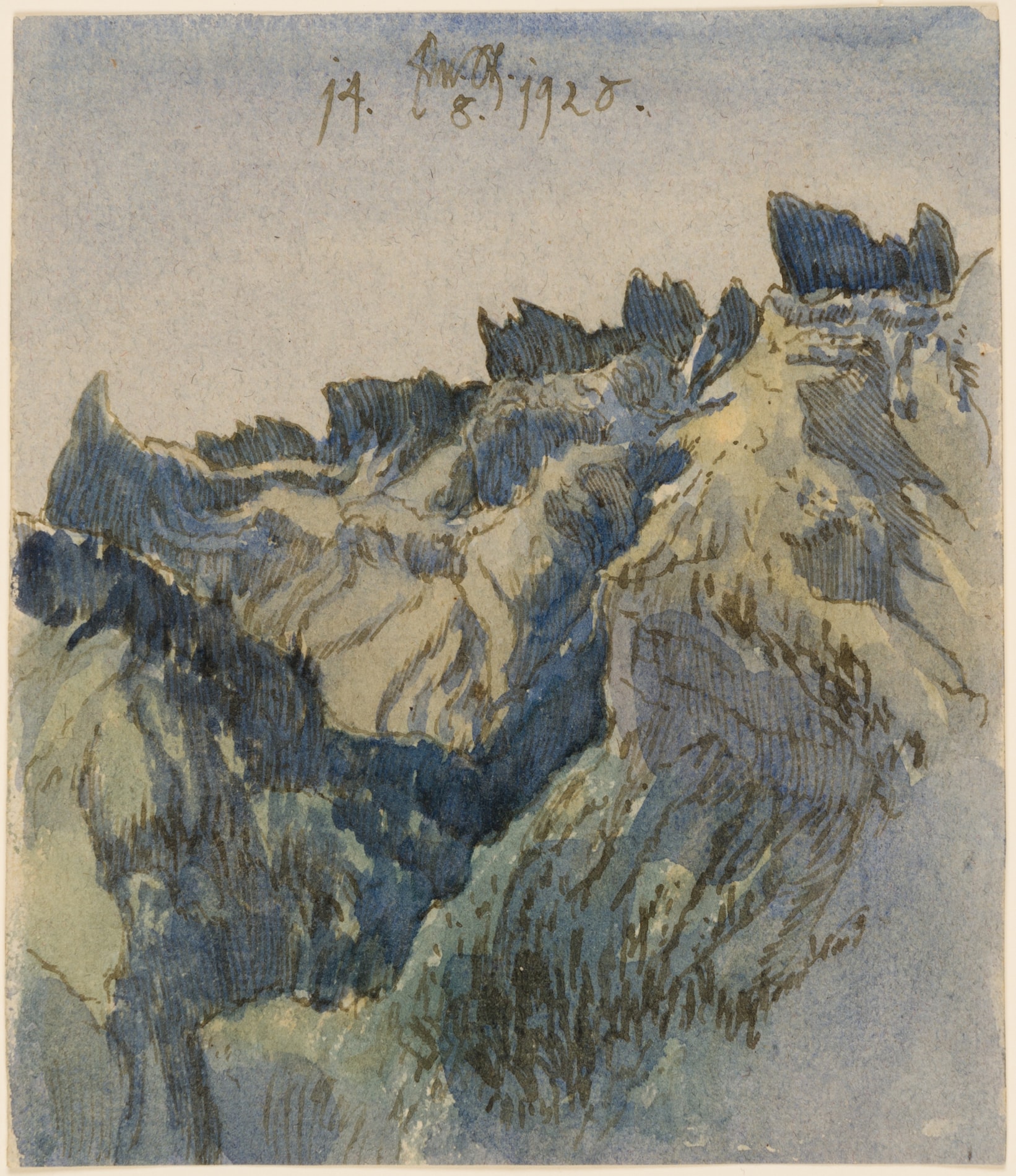

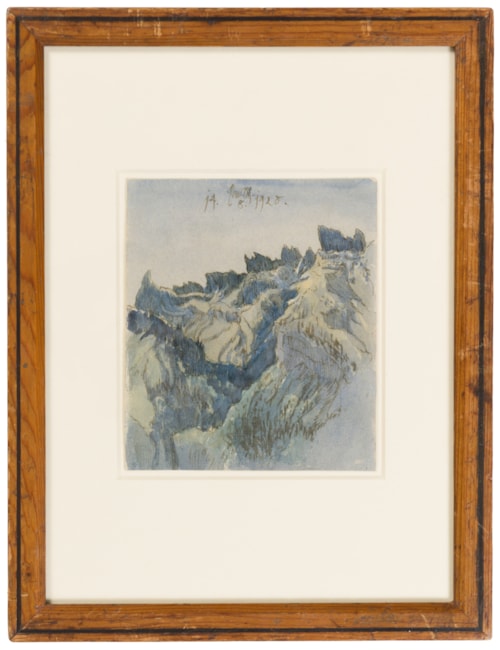

Edmund STEPPES

(Burghausen 1873 - Dusseldorf 1968)

Mountain Landscape

Sold

Pen and brown ink and watercolour.

Signed and dated Edm. St. / 14. 8. 1920. at the upper centre.

148 x 128 mm. (5 3/4 x 5 in.)

Signed and dated Edm. St. / 14. 8. 1920. at the upper centre.

148 x 128 mm. (5 3/4 x 5 in.)

Dated the 14th of August 1920, this is a characteristic example of Edmund Steppes’s atmospheric landscapes, in which nature is perceived in a dreamlike manner. As an early writer noted of these paintings and drawings, ‘An inborn flow of feeling tinged with a shade of melancholy pervades this work…Steppes is the painter of silence. He loves the quiet valley and the lonely mountain tops; he is attracted also to solitary trees, especially when they have a bizarre silhouette. Bright sunlight is not to his taste, he prefers the subdued light of dawn, evening, and moonlight. Evidences are present in his art that he is not averse to modern modes of expression, but he loves to persevere in his own style.’

A stylistically comparable drawing by Steppes of a cliff face in the Dolomites is in the collection of the Oberhausmuseum in Passau.

A stylistically comparable drawing by Steppes of a cliff face in the Dolomites is in the collection of the Oberhausmuseum in Passau.

The landscape painter Edmund Carl Ferdinand Steppes studied at the private art school established by the genre and portrait painter Heinrich Knirr in Munich from 1891, and in 1892 entered the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich, studying with the historical painter Gabriel Hackl. In the summer of 1893 the young artist exhibited his work at the Munich Kunstverein, an honour usually only reserved for students at the Akademie who had been nominated as ‘Meisterschülern’, or master students, which he was not. The following year he left the academy, perhaps because of the resentment his success has provoked among students and professors, and completed his artistic training on his own, making sketching trips to the Swabian Alps and Switzerland. Steppes exhibited at the Munich Secession from 1897 onwards, and by the turn of the century he had begun to enjoy a measure of success, selling his work to private collectors and enjoying the support of a number of influential figures in the German art world, such as the painters Emil Lugo and Hans Thoma.

Steppes’s work was first acquired by a German museum in 1902, and his work began to be exhibited widely throughout Germany. In 1906 some fifty of his works were shown at the Kunstverein in Heidelberg and in other exhibitions in Munich, Frankfurt and Bonn, and the following year Steppes published his polemical book Die deutsche Malerei. From 1910 he had a number of solo exhibitions and the first illustrated monograph on his work appeared. He also produced some seventy etchings, mainly between 1912 and 1915.

Exempted from military service, Steppes was able to continue painting during much of the First World War. As one English critic, writing just before the outbreak of war in 1914, noted of him, ‘Evidences are present in his art that he is not averse to modern modes of expression, but he loves to persevere in his own style…he prefers to be considered a self-taught artist, as he learned most from nature and the old masters.’

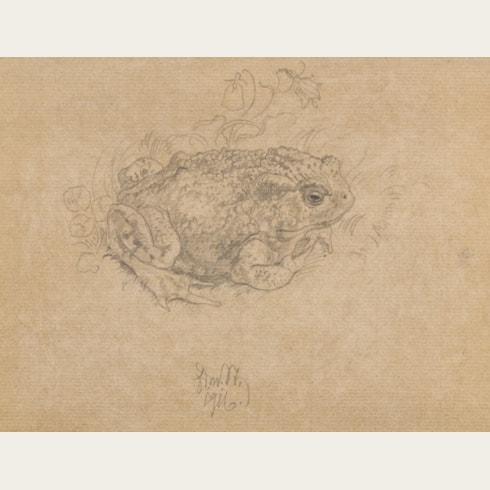

Steppes made an intensive study of the art of German and Netherlandish Old Masters, particularly of the late Gothic period, and was drawn to the works of Albrecht Altdorfer and Matthias Grünewald, whose Isenheim altarpiece in Colmar he found particularly inspirational. He seems to have largely ignored the religious aspect of such paintings, however, in favour of an appreciation of the often bizarre and fantastical landscapes in their backgrounds, which would find their way into his own work. After the war Steppes produced relatively few paintings, and instead began to devote himself to drawing; producing numerous small-scale studies with detailed observations of nature, made on sketching expeditions around southern Germany. These drawings and watercolours – of flowers, plants and leaves, as well as gnarled trees and strange rock formations – account for some of his most distinctive work.

Steppes maintained a comprehensive catalogue of his paintings between 1893 and 1947. In 1927 he was appointed a Professor by the Bavarian Ministry of Culture, and in the 1930s his work began to command ever higher prices. A member of the National Socialist party since 1932, Steppes exhibited several works at the propagandic Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung exhibitions of the 1930s and 1940s in Munich, where his paintings were bought by Adolf Hitler, Joseph Goebbels and Martin Bormann. In 1943 he was awarded the Goethe Medal for Art and Science by Hitler, and in 1944 his name was included on the so-called ‘Gottbegnadeten-Liste’ of artists, writers, actors, composers and musicians considered crucial to German culture and therefore exempt from military mobilization during the latter stages of the war. In January 1945 his studio was destroyed by an Allied bomb, which led to the loss of numerous drawings and around forty paintings. When the war ended, Steppes stood trial for his membership of the Nazi party, but was judged to have joined the party for idealistic and financial reasons and not through political motivation, and thus only received a fine. He settled in the town of Tuttlingen in Baden-Württemburg, on the outskirts of the Swabian Jura, and resumed his career, exhibiting occasionally at the Haus der Kunst in Munich. In 1963 a retrospective exhibition of Steppes’s work was held in Tuttlingen, on the occasion of the artist’s 90th birthday.

Steppes spent much time on sketching expeditions in the Bavarian countryside around Munich, the Swabian Alps and the Allgäu region. While his landscape paintings were worked on in the studio, they were always based on sketches made on the spot. Writing from Vienna in 1910, one English critic noted that ‘There is something very seductive in the landscapes of Edmund Steppes, which met with much success when exhibited at Heller’s Art Rooms a short time ago. The artist selects his motives from the low undulating plains, the hills, the trees whose foliage is gently stirred by the breeze or by the soughing of the winds. There is a feeling of rest and repose in his pictures...Above all, there is depth of thought and earnestness in Steppes’ composition, a keen sentiment for the decorative, and a feeling for style, expressed with an intimacy and knowledge born of understanding and love. Nature has breathed her secret to him, has revealed to him things beyond the general ken of mankind, and, moreover, has taught him how to reveal her glories to others in the loveliest and most touching of tones.’ Steppes’s landscapes, while remaining true to nature, often reveal a concurrent element of mystical symbolism and fantasy.

The largest collection of drawings by Edmund Steppes is today to be found in the Städtische Galerie in Albstadt, in Baden-Württemberg, which houses nearly eighty paintings, drawings, watercolours and prints by the artist. A large number of etchings by the artist are in the collection of the Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum in Braunschweig, and other important groups of his works are in the museums of Karlsruhe, Munich, Stuttgart and elsewhere.

Steppes’s work was first acquired by a German museum in 1902, and his work began to be exhibited widely throughout Germany. In 1906 some fifty of his works were shown at the Kunstverein in Heidelberg and in other exhibitions in Munich, Frankfurt and Bonn, and the following year Steppes published his polemical book Die deutsche Malerei. From 1910 he had a number of solo exhibitions and the first illustrated monograph on his work appeared. He also produced some seventy etchings, mainly between 1912 and 1915.

Exempted from military service, Steppes was able to continue painting during much of the First World War. As one English critic, writing just before the outbreak of war in 1914, noted of him, ‘Evidences are present in his art that he is not averse to modern modes of expression, but he loves to persevere in his own style…he prefers to be considered a self-taught artist, as he learned most from nature and the old masters.’

Steppes made an intensive study of the art of German and Netherlandish Old Masters, particularly of the late Gothic period, and was drawn to the works of Albrecht Altdorfer and Matthias Grünewald, whose Isenheim altarpiece in Colmar he found particularly inspirational. He seems to have largely ignored the religious aspect of such paintings, however, in favour of an appreciation of the often bizarre and fantastical landscapes in their backgrounds, which would find their way into his own work. After the war Steppes produced relatively few paintings, and instead began to devote himself to drawing; producing numerous small-scale studies with detailed observations of nature, made on sketching expeditions around southern Germany. These drawings and watercolours – of flowers, plants and leaves, as well as gnarled trees and strange rock formations – account for some of his most distinctive work.

Steppes maintained a comprehensive catalogue of his paintings between 1893 and 1947. In 1927 he was appointed a Professor by the Bavarian Ministry of Culture, and in the 1930s his work began to command ever higher prices. A member of the National Socialist party since 1932, Steppes exhibited several works at the propagandic Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung exhibitions of the 1930s and 1940s in Munich, where his paintings were bought by Adolf Hitler, Joseph Goebbels and Martin Bormann. In 1943 he was awarded the Goethe Medal for Art and Science by Hitler, and in 1944 his name was included on the so-called ‘Gottbegnadeten-Liste’ of artists, writers, actors, composers and musicians considered crucial to German culture and therefore exempt from military mobilization during the latter stages of the war. In January 1945 his studio was destroyed by an Allied bomb, which led to the loss of numerous drawings and around forty paintings. When the war ended, Steppes stood trial for his membership of the Nazi party, but was judged to have joined the party for idealistic and financial reasons and not through political motivation, and thus only received a fine. He settled in the town of Tuttlingen in Baden-Württemburg, on the outskirts of the Swabian Jura, and resumed his career, exhibiting occasionally at the Haus der Kunst in Munich. In 1963 a retrospective exhibition of Steppes’s work was held in Tuttlingen, on the occasion of the artist’s 90th birthday.

Steppes spent much time on sketching expeditions in the Bavarian countryside around Munich, the Swabian Alps and the Allgäu region. While his landscape paintings were worked on in the studio, they were always based on sketches made on the spot. Writing from Vienna in 1910, one English critic noted that ‘There is something very seductive in the landscapes of Edmund Steppes, which met with much success when exhibited at Heller’s Art Rooms a short time ago. The artist selects his motives from the low undulating plains, the hills, the trees whose foliage is gently stirred by the breeze or by the soughing of the winds. There is a feeling of rest and repose in his pictures...Above all, there is depth of thought and earnestness in Steppes’ composition, a keen sentiment for the decorative, and a feeling for style, expressed with an intimacy and knowledge born of understanding and love. Nature has breathed her secret to him, has revealed to him things beyond the general ken of mankind, and, moreover, has taught him how to reveal her glories to others in the loveliest and most touching of tones.’ Steppes’s landscapes, while remaining true to nature, often reveal a concurrent element of mystical symbolism and fantasy.

The largest collection of drawings by Edmund Steppes is today to be found in the Städtische Galerie in Albstadt, in Baden-Württemberg, which houses nearly eighty paintings, drawings, watercolours and prints by the artist. A large number of etchings by the artist are in the collection of the Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum in Braunschweig, and other important groups of his works are in the museums of Karlsruhe, Munich, Stuttgart and elsewhere.