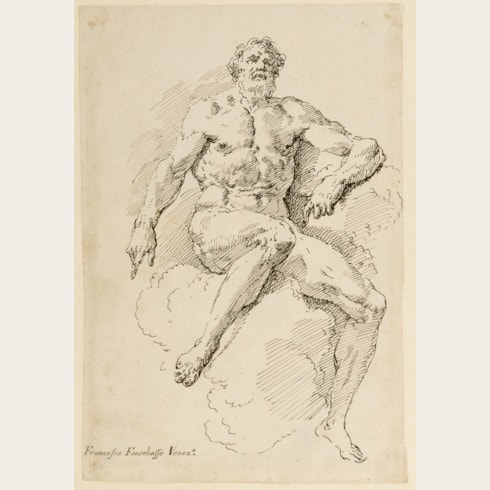

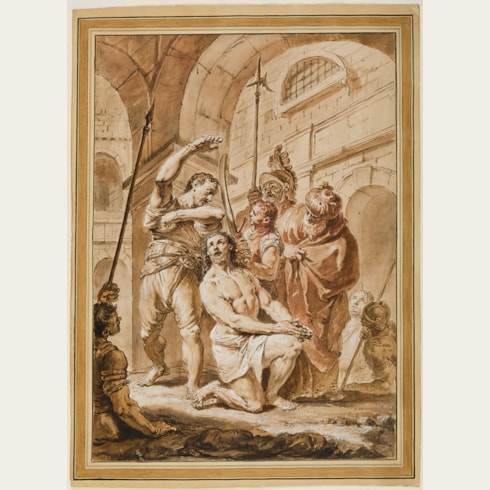

Francesco FONTEBASSO

(Venice 1707 - Venice 1769)

Clorinda Pleads for the Life of Sophronia and Olindo

Watercolour, pen and brown ink and light brown wash, over an underdrawing in black chalk.

The corners of the sheet cut.

200 x 268 mm. (7 7/8 x 10 1/2 in.)

The corners of the sheet cut.

200 x 268 mm. (7 7/8 x 10 1/2 in.)

Previously identified as the martyrdom of Saints Placidus and Flavia, the subject of this watercolour drawing instead depicts an episode from Torquato Tasso’s epic poem Gerusalemme Liberata. Published in 1575, Tasso’s romantic poem about the First Crusade was a popular source for Venetian artists of the 18th century. The scene is taken from the second Canto of the book, in which Aladine, the Saracen king of Jerusalem, threatens to execute the entire Christian community of the city in punishment for the supposed theft of a sacred icon of the Virgin Mary. Sophronia, a young Christian maiden of great beauty and virtue, volunteers to bear the blame for the incident to save her people, and falsely confesses to the theft. Aladine orders her to be burned at the stake, but, desperate to save her from the flames, her lover Olindo then proclaims himself to be the thief, and begs the king to let him die in her stead. Aladine, who knows that the two young lovers are innocent, nevertheless condemns Sophronia and Olindo to die together, bound to the same stake and tied back to back so that they cannot see each other. Clorinda, a female Persian warrior armed and on horseback, appears just before the pyre is lit. Hearing of their plight, she takes pity on the two Christian lovers and gains their freedom by promising in return her services to Aladine in his coming war against the Crusaders.

This drawing, which has been dated by the Fontebasso scholar Marina Magrini to the middle of the 1750s, reveals something of the long-lasting influence of his first teacher, Sebastiano Ricci, in its composition, colouring and brushwork. While the present sheet has remained unrelated to any surviving painting or fresco by Francesco Fontebasso, it should be noted that a now-lost painting of the same subject by the artist is recorded in the 19th century; a vertical oval canvas of ‘Il Supplizio di Sofronia e Olindo’ which was in the collection of Carlo Berra in Venice in 1863.

This drawing, which has been dated by the Fontebasso scholar Marina Magrini to the middle of the 1750s, reveals something of the long-lasting influence of his first teacher, Sebastiano Ricci, in its composition, colouring and brushwork. While the present sheet has remained unrelated to any surviving painting or fresco by Francesco Fontebasso, it should be noted that a now-lost painting of the same subject by the artist is recorded in the 19th century; a vertical oval canvas of ‘Il Supplizio di Sofronia e Olindo’ which was in the collection of Carlo Berra in Venice in 1863.

A pupil of Sebastiano Ricci, Francesco Fontebasso spent a brief period of study in Rome before returning to his native Venice, where he produced a series of engravings after Ricci’s paintings. He established his career in Venice, painting several altarpieces for local churches, and was soon in some demand as a fresco painter. In 1734 he decorated the ceiling of the church of the Gesuiti in Venice, and two years later painted a fresco cycle for the church of Santa Maria Annunziata in Trent. Fontebasso worked for members of the Venetian aristocracy such as the Barbarigo family, for whom he painted decorative fresco cycles in the Palazzo Duodo and the Palazzo Barbarigo.

Apart from his success as a fresco painter, Fontebasso made a particular specialty of small-scale devotional easel pictures and modelli, and also worked as an engraver and a designer of book illustrations. From 1756 onwards he was a professor at the Accademia Veneziana, and in 1761 he visited St. Petersburg at the invitation of the Empress Catherine II. Fontebasso remained in Russia for almost two years, completing a number of decorative projects for the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg and other Imperial palaces, as well as painting portraits and genre studies. Although appointed a Professor at the Imperial Academy of Arts, he chose to return to Venice in 1762, where he rose to the position of principe of the Accademia in 1768, shortly before his death.

As Filippo Pedrocco has noted, ‘Fontebasso was a prolific draughtsman and produced sparkling, delicate work in the best tradition of the Venetian Rococo.’1 Like his paintings, his drawings are best described as a synthesis of the manner of his teacher Sebastiano Ricci with the drawings of Fontebasso’s slightly older contemporary, Giambattista Tiepolo. As Pedrocco points out, ‘at different stages of his career his graphic work sometimes reflects the influence of one, sometimes the other. He was not simply a passive interpreter of their work, however, and was capable of achieving a high degree of poetry independent of their influence. Examples can be found among his many ‘finished’ drawings, evidently intended for collectors.’ Most of Fontebasso’s drawings are executed in pen and ink, and while only relatively few may be connected with his paintings, several can be related to the handful of etchings that he made.

Provenance

Anonymous sale, London, Christie’s, 15 April 1980, lot 119

Adolphe Stein, Paris, in 1981

Wolfgang Ratjen, Munich

Roberto Franchi, Bologna

Christian Lapeyre, Milan, in 1994

P. & D. Colnaghi, London, in 1994

Private collection.

Adolphe Stein, Paris, in 1981

Wolfgang Ratjen, Munich

Roberto Franchi, Bologna

Christian Lapeyre, Milan, in 1994

P. & D. Colnaghi, London, in 1994

Private collection.

Literature

Marina Magrini, Francesco Fontebasso: I disegni, in Saggi e memorie di storia dell arte, Vol.17, 1990, p.190, no.156, p.355, fig.64 (where dated to the mid-1750s).

Exhibition

London, Bury Street Gallery, Master Drawings presented by Adolphe Stein, 1981, no.50; New York and London, Colnaghi, Master Drawings, 1994, no.38; Stanford University, Cantor Center for Visual Arts, Classic Taste: Drawings and Decorative Arts from the Collection of Horace Brock, 2000.