Claudio BRAVO

(Valparaiso 1936 - Taroudant 2011)

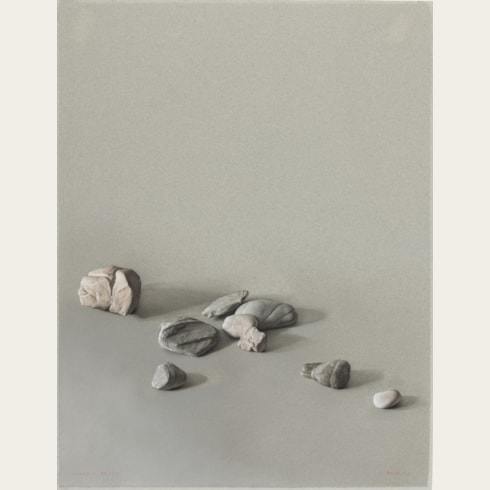

Still Life

Sold

Pastel on light grey paper.

Signed and dated CLAUDIO BRAVO / MCMLXXXVII in red chalk at the lower right.

750 x 1097 mm. (29 1/2 x 43 1/4 in.) [sheet]

Signed and dated CLAUDIO BRAVO / MCMLXXXVII in red chalk at the lower right.

750 x 1097 mm. (29 1/2 x 43 1/4 in.) [sheet]

In 1985 Claudio Bravo noted that ‘Drawing and color are the bases of my work. However, I seem to be doing fewer drawings these days – either preliminary drawings or studies for paintings. I draw directly onto the canvas and use that as the basis for my colors. I find that drawing is less and less important for me…I had a large exhibition of my pastels at the Marlborough Gallery in New York in 1985. I realized then the magic quality of the medium. Pastels seem to embody a special light effect, directly reflecting the sun of mid-day while oil evokes the qualities of afternoon sun with its more sober tones. I feel that there are relatively few great works in pastel. Someday I’d like to do a large-scale human figure in pastel of the importance of Quentin de la Tour’s portrait of Madame de Pompadour, the most important work ever done, I think, in that medium. I also have enormous regard for the pastels of Degas and Manet.’ In another, later interview, Bravo pointed out that ‘Sometimes I don’t know what to paint and I paint something right in front of me; other times I look for the subject. I buy an object I like, I mix it with another, I put it somewhere with a particular light I like and I gradually move it, I spend hours moving it back and forth.’

This very large still life, superbly executed in pastel, was drawn in Tangier in 1987. The folded cloth in the centre of the composition reappears as a tablecloth in a large still life painting of Boxes, dated 1986, while similar stone mortars are found in several of the artist’s still life compositions, such as a pastel of 1982 and an oil painting executed the following year.

Works such as this are a testament to Bravo’s abiding interest in the classical tradition of European still life painting, and in particular the bodegón paintings produced in Spain in the late 16th and 17th century. As the artist’s friend, the Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa, has written of Bravo, ‘His true masters are the great classical masters, particularly Spanish 17th century, the Golden Age of Baroque, such as Fray Juan Sánchez Cotán, Antonio de Pereda or Francisco de Zurbarán, who revolutionized the treatment of the object, conferring on their still lifes – through a scrupulous study of details and the play of light – a dignity and intensity which appear to emancipate them from the inert and humanize them. Claudio Bravo has updated this old school with his oil paintings, pastels and drawings of flowers, fruit, vegetables, jugs, tablecloths, mortars, cruets, cooking pots, ostrich eggs, rugs, glasses, stones, and hampers which it would be unfair to call “still life”, since that label immediately suggests the inanimate, the decorative…these images shimmer like precious jewels, they become giant-like heroes whose outstanding presence has desolated their surroundings.’

This very large still life, superbly executed in pastel, was drawn in Tangier in 1987. The folded cloth in the centre of the composition reappears as a tablecloth in a large still life painting of Boxes, dated 1986, while similar stone mortars are found in several of the artist’s still life compositions, such as a pastel of 1982 and an oil painting executed the following year.

Works such as this are a testament to Bravo’s abiding interest in the classical tradition of European still life painting, and in particular the bodegón paintings produced in Spain in the late 16th and 17th century. As the artist’s friend, the Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa, has written of Bravo, ‘His true masters are the great classical masters, particularly Spanish 17th century, the Golden Age of Baroque, such as Fray Juan Sánchez Cotán, Antonio de Pereda or Francisco de Zurbarán, who revolutionized the treatment of the object, conferring on their still lifes – through a scrupulous study of details and the play of light – a dignity and intensity which appear to emancipate them from the inert and humanize them. Claudio Bravo has updated this old school with his oil paintings, pastels and drawings of flowers, fruit, vegetables, jugs, tablecloths, mortars, cruets, cooking pots, ostrich eggs, rugs, glasses, stones, and hampers which it would be unfair to call “still life”, since that label immediately suggests the inanimate, the decorative…these images shimmer like precious jewels, they become giant-like heroes whose outstanding presence has desolated their surroundings.’

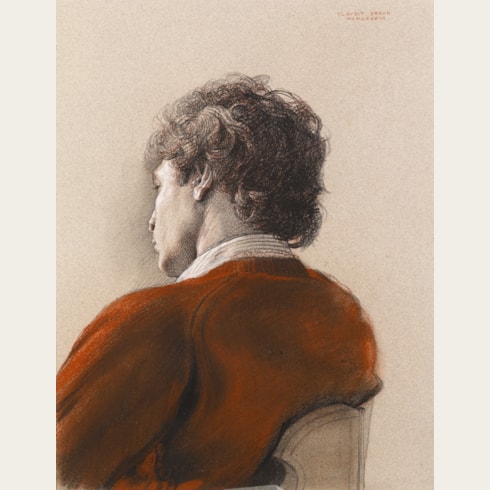

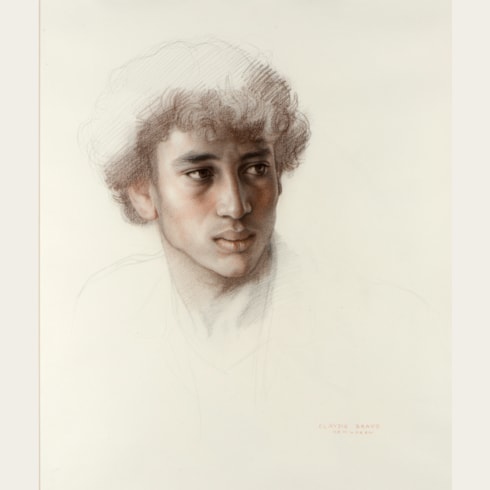

Born in Valparaiso in Chile, Claudio Bravo received a Jesuit education in Santiago and there took art classes in the studio of the painter Miguel Venegas Cienfuentes, eventually deciding to become an artist himself. He had his first exhibition at the age of seventeen, and was soon much in demand as a portrait painter. In 1961, after several years living and working in Santiago and Concepción, Bravo left Chile for Europe. Settling in Madrid, he established a very successful career as a painter and society portraitist. In 1968 he spent six months working in the Philippines, and in 1970 had his first solo exhibition in New York. In 1972 he abandoned his busy life in Madrid for a large house and studio in Tangier in Morocco, where he began to focus on still life and landscape painting. Dividing his year between his studio in Tangier and another in Marrakech, as well as one in the far south of Chile, Bravo enjoyed a successful career until the end of his life. As one scholar noted, at the time of an exhibition of his work which toured four American museums in 1987 and 1988, ‘Claudio Bravo is one of the most significant artists working in a realist mode today. A painter and draftsman with a singularly fertile imagination, Bravo draws upon a myriad of sources in the art of the past and present, combining them in a uniquely personal manner.’

In 1994 a large exhibition of Bravo's paintings was mounted at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Santiago, Chile. Works by Claudio Bravo are in the collections of the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Ludwig Museum in Cologne, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Princeton University Art Museum, the Museum Boijmans-van Beuningen in Rotterdam, the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Santiago and elsewhere.

Long recognized as a superb draughtsman, Bravo was a master of pencil, coloured chalks and pastel, which he applied with precision and delicacy.

Provenance

Anonymous sale, New York, Christie’s, 16 November 1994, lot 43

Private collection.

Private collection.