Alfred STEVENS

(Brussels 1823 - Paris 1906)

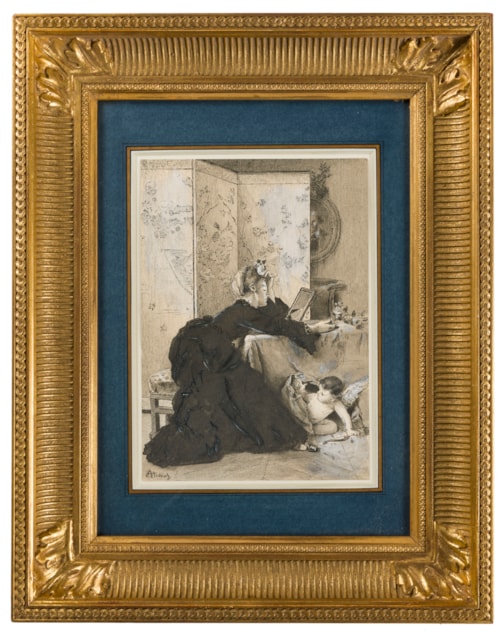

The Young Widow (La jeune veuve or Le dernier jour de veuvage)

Sold

Pen and black ink and black wash, heightened with touches of white gouache.

Signed AStevens at the lower left.

Titled LA JEUNE VEUVE and inscribed (Fable de Lafontaine) on the original mount.

Signed, dedicated and dated à mon cher Dr. Campbell / souvenir de reconnaissance / Alfred Stevens / Paris 31 Décembre 1874 on the old backing board.

237 x 162 mm. (9 3/8 x 6 3/8 in.)

Signed AStevens at the lower left.

Titled LA JEUNE VEUVE and inscribed (Fable de Lafontaine) on the original mount.

Signed, dedicated and dated à mon cher Dr. Campbell / souvenir de reconnaissance / Alfred Stevens / Paris 31 Décembre 1874 on the old backing board.

237 x 162 mm. (9 3/8 x 6 3/8 in.)

The present sheet is related to Alfred Stevens’ painting The Young Widow (La jeune veuve) of c.1873-1874, today in the Musée Royal de Mariemont in Morlanwelz, south of Brussels. The painting was purchased in April 1875 from the Brussels art dealer Henry Le Roy et fils by the Belgian collector Arthur Warocqué (1835-1880), whose widow later presented it to the museum. As Peter Mitchell describes the subject, ‘The young widow in black, with the portrait of the lost husband in the background, looks in the mirror to reassure herself that she is still attractive and able to attract a new admirer. She need have no worries because the promise of new love is assured by the well-timed appearance of Cupid from under the table.’ In his monograph on Stevens, published in 1906, Camille Lemonnier described The Young Widow as having ‘the charming caprice of a Fragonard’.

The painting was one of eighteen works by Stevens shown at the Exposition Internationale de peinture at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris in 1882, and was also exhibited at the Salon des Champ de Mars in 1890. On the latter occasion the artist wrote to Mme. Warocqué requesting the loan of the picture, noting that ‘This painting, which I consider to be one of my best, is unknown in Paris, and for the sake of my reputation I would so much like to have it seen.’ In a later letter to her, he mentioned that ‘your painting - The Young Widow - before sending it to the Champ de Mars, it was seen in my studio by many painters, who were all enthusiastic about it, which made me so happy, that I would like to tell you and express again all my gratitude to you for having had the goodness to grant me it for my exhibition.’

As Mitchell has noted of the painting of The Young Widow, ‘Critics at the time were unhappy that the ‘painter of modern life’ had lapsed into the realms of the imaginary. Clearly, they did not appreciate that it was an illustration to Les Fables by La Fontaine, a source of inspiration to artists from the 17th century onwards.’ Indeed, the present sheet is also closely related to a sketch by Stevens for an illustration of the fable ‘La jeune veuve’, intended for an edition of the Fables of Jean de La Fontaine published in Paris in 1873.

Two other drawings by Alfred Stevens of the same composition - a preparatory sketch in pen and watercolour in an American private collection and a more finished drawing in watercolour and gouache recently on the Paris art market – are, like the present sheet, likely to have been drawn as studies for the 1873 illustration before being reused for the painting of The Young Widow. All three works on paper differ from the final painting in several details, notably the fact that the Japanese paper screen seen in the drawings was replaced by two doors and the edge of a large tapestry in the painting.

As noted by the artist’s inscription on the old backing board, the present sheet was given by the artist to a Dr. Campbell on New Year’s Eve 1874. This was probably the English-born physician Dr. Charles James Campbell (1820-1879), one of the leading obstetricians in Paris and a pioneer of obstetrical anaesthesia in France. Over the course of his distinguished career Campbell performed or supervised over 1,500 deliveries. As his friend, the writer Octave Mirbeau, noted of him, ‘There was in his exquisite way of speaking to women such a paternal grace, such an envelopment of respect mixed with the authority of the doctor, that they all adored him…There is not a woman belonging to Parisian society who has not had recourse to Dr. Campbell's radiance and skill. Honoured with the favours and esteem of the Empress, he was the fashionable doctor, the obligatory doctor of all grace. A woman would not have believed herself well delivered if she had not been delivered by him. People were grateful for his care, and his flat in the Rue Royale was full of superb gifts and precious souvenirs.’

The painting was one of eighteen works by Stevens shown at the Exposition Internationale de peinture at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris in 1882, and was also exhibited at the Salon des Champ de Mars in 1890. On the latter occasion the artist wrote to Mme. Warocqué requesting the loan of the picture, noting that ‘This painting, which I consider to be one of my best, is unknown in Paris, and for the sake of my reputation I would so much like to have it seen.’ In a later letter to her, he mentioned that ‘your painting - The Young Widow - before sending it to the Champ de Mars, it was seen in my studio by many painters, who were all enthusiastic about it, which made me so happy, that I would like to tell you and express again all my gratitude to you for having had the goodness to grant me it for my exhibition.’

As Mitchell has noted of the painting of The Young Widow, ‘Critics at the time were unhappy that the ‘painter of modern life’ had lapsed into the realms of the imaginary. Clearly, they did not appreciate that it was an illustration to Les Fables by La Fontaine, a source of inspiration to artists from the 17th century onwards.’ Indeed, the present sheet is also closely related to a sketch by Stevens for an illustration of the fable ‘La jeune veuve’, intended for an edition of the Fables of Jean de La Fontaine published in Paris in 1873.

Two other drawings by Alfred Stevens of the same composition - a preparatory sketch in pen and watercolour in an American private collection and a more finished drawing in watercolour and gouache recently on the Paris art market – are, like the present sheet, likely to have been drawn as studies for the 1873 illustration before being reused for the painting of The Young Widow. All three works on paper differ from the final painting in several details, notably the fact that the Japanese paper screen seen in the drawings was replaced by two doors and the edge of a large tapestry in the painting.

As noted by the artist’s inscription on the old backing board, the present sheet was given by the artist to a Dr. Campbell on New Year’s Eve 1874. This was probably the English-born physician Dr. Charles James Campbell (1820-1879), one of the leading obstetricians in Paris and a pioneer of obstetrical anaesthesia in France. Over the course of his distinguished career Campbell performed or supervised over 1,500 deliveries. As his friend, the writer Octave Mirbeau, noted of him, ‘There was in his exquisite way of speaking to women such a paternal grace, such an envelopment of respect mixed with the authority of the doctor, that they all adored him…There is not a woman belonging to Parisian society who has not had recourse to Dr. Campbell's radiance and skill. Honoured with the favours and esteem of the Empress, he was the fashionable doctor, the obligatory doctor of all grace. A woman would not have believed herself well delivered if she had not been delivered by him. People were grateful for his care, and his flat in the Rue Royale was full of superb gifts and precious souvenirs.’

From the age of seventeen, Alfred Emile Leopold Stevens trained in Brussels with François-Joseph Navez, who had been a pupil of Jacques-Louis David. In 1844 he moved to Paris to study with Camille Roqueplan. (He may also have received some artistic instruction from Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts.) Stevens returned briefly to Brussels in 1849 and exhibited at the Salon there in 1851, but by the following year he was back in Paris, where he was to live and work for the remainder of his career. He made his debut at the Paris Salon in 1853, where he won a third-class medal and had one of his paintings acquired by the State for the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Marseille. Within a few years Stevens had established his favoured genre of intimate scenes of women in modern interiors for which he was to become famous.

By the 1860s Stevens had become one of the best-known artists in Paris, part of a literary and artistic circle that included the writers Charles Baudelaire and Théophile Gautier and the painters Edouard Manet, Berthe Morisot, Jacques-Emile Blanche and Edgar Degas, to whom Stevens was particularly close. His first significant public success came at the Exposition Universelle of 1867, where he showed eighteen pictures and won a first-class medal. By this time, he had already come to the attention of several important collectors, particularly in his native Belgium. Indeed, in 1866 paintings by Stevens were acquired by both King Léopold II of Belgium and the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. The artist lived in a series of elegant studios in Paris, lavishly decorated with a fine collection of paintings, furniture and objects, and exhibited with much success in Paris, Brussels, Antwerp and elsewhere.

Stevens developed a particular speciality of paintings of the elegant women of Paris, dressed in their finery or getting ready for balls or visits. He was a master at depicting rich silks, crinolines, ribbons and jewellery, and in his studio kept several lavish dresses to be used by his sitters. (He also occasionally borrowed dresses from such friends and clients as the Austrian socialite Princess Pauline von Metternich.) The artist achieved a considerable reputation for these stylish works, and his great success allowed him to establish a luxurious lifestyle, and to build a collection of Japanese and oriental objects. It was in the 1870s that his paintings first came to the attention of American collectors such as the Vanderbilts in New York and William Walters in Baltimore, and a large number of significant pictures by the artist are today to be found in American museums. In the 1880s Stevens began teaching young artists in his studio, many of whom were women. At the end of the decade he worked, in collaboration with a former pupil, Henri Gervex, on a monumental painting entitled Panorama of the History of the Century, which was displayed in a special pavilion at the Exposition Universelle of 1889. Stevens continued to paint until 1899, when a bad fall left him confined to a wheelchair. The following year he was accorded a large retrospective exhibition of more than two hundred works at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris; an unprecedented honour for a living artist.

Stevens’s paintings were much admired by many of his contemporaries, including Degas, Manet, Paul-César Helleu, Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir. At his death in 1906, one obituary praised the artist’s ability to ‘make a fresh and living art out of material which no painter had seriously employed for half a century – the fashionable woman of Paris – and so to become an influence upon the photographic art of Tissot, the milliner’s work of Carolus-Duran, and to a lesser degree, perhaps, upon men of the rank of Manet and Whistler…Stevens’s best work anticipates not a few of the qualities of design and spacing that made Whistler’s fame, coupled with a true painter’s sense of pigment, and a touch so light, so orderly, so expressive and so tender that his pictures were as much admired by artists as his subjects were by the fashionable public.’ A comprehensive memorial exhibition of Stevens’s work was held in Brussels and Antwerp in 1907.

By the 1860s Stevens had become one of the best-known artists in Paris, part of a literary and artistic circle that included the writers Charles Baudelaire and Théophile Gautier and the painters Edouard Manet, Berthe Morisot, Jacques-Emile Blanche and Edgar Degas, to whom Stevens was particularly close. His first significant public success came at the Exposition Universelle of 1867, where he showed eighteen pictures and won a first-class medal. By this time, he had already come to the attention of several important collectors, particularly in his native Belgium. Indeed, in 1866 paintings by Stevens were acquired by both King Léopold II of Belgium and the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. The artist lived in a series of elegant studios in Paris, lavishly decorated with a fine collection of paintings, furniture and objects, and exhibited with much success in Paris, Brussels, Antwerp and elsewhere.

Stevens developed a particular speciality of paintings of the elegant women of Paris, dressed in their finery or getting ready for balls or visits. He was a master at depicting rich silks, crinolines, ribbons and jewellery, and in his studio kept several lavish dresses to be used by his sitters. (He also occasionally borrowed dresses from such friends and clients as the Austrian socialite Princess Pauline von Metternich.) The artist achieved a considerable reputation for these stylish works, and his great success allowed him to establish a luxurious lifestyle, and to build a collection of Japanese and oriental objects. It was in the 1870s that his paintings first came to the attention of American collectors such as the Vanderbilts in New York and William Walters in Baltimore, and a large number of significant pictures by the artist are today to be found in American museums. In the 1880s Stevens began teaching young artists in his studio, many of whom were women. At the end of the decade he worked, in collaboration with a former pupil, Henri Gervex, on a monumental painting entitled Panorama of the History of the Century, which was displayed in a special pavilion at the Exposition Universelle of 1889. Stevens continued to paint until 1899, when a bad fall left him confined to a wheelchair. The following year he was accorded a large retrospective exhibition of more than two hundred works at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris; an unprecedented honour for a living artist.

Stevens’s paintings were much admired by many of his contemporaries, including Degas, Manet, Paul-César Helleu, Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir. At his death in 1906, one obituary praised the artist’s ability to ‘make a fresh and living art out of material which no painter had seriously employed for half a century – the fashionable woman of Paris – and so to become an influence upon the photographic art of Tissot, the milliner’s work of Carolus-Duran, and to a lesser degree, perhaps, upon men of the rank of Manet and Whistler…Stevens’s best work anticipates not a few of the qualities of design and spacing that made Whistler’s fame, coupled with a true painter’s sense of pigment, and a touch so light, so orderly, so expressive and so tender that his pictures were as much admired by artists as his subjects were by the fashionable public.’ A comprehensive memorial exhibition of Stevens’s work was held in Brussels and Antwerp in 1907.

Provenance

Given by the artist to a Dr. Campbell, probably Dr. Charles James Campbell, Paris

Private collection, Bordeaux.

Private collection, Bordeaux.