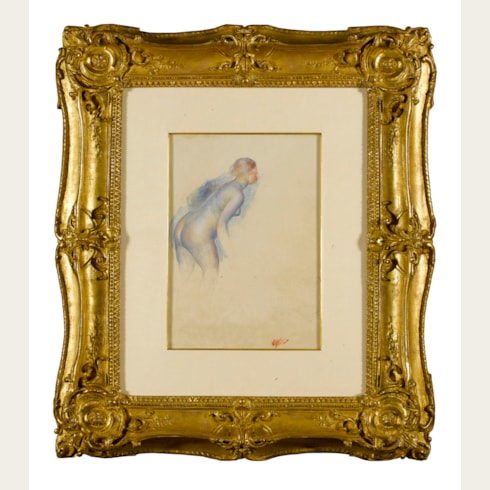

Pierre Auguste RENOIR

(Limoges 1841 - Cagnes-sur-Mer 1919)

Mediterranean Landscape

Sold

Watercolour and gouache on buff paper.

Signed with the artist’s initial R. in pencil at the lower left.

145 x 273 mm. (5 3/4 x 10 3/4 in.) [image]

159 x 306 mm. (6 1/4 x 12 in.) [sheet]

Signed with the artist’s initial R. in pencil at the lower left.

145 x 273 mm. (5 3/4 x 10 3/4 in.) [image]

159 x 306 mm. (6 1/4 x 12 in.) [sheet]

Although he is best known for his figure paintings, Auguste Renoir painted and drew landscape subjects throughout his career. As he once told the art dealer René Gimpel, near the end of his life, ‘I can’t paint nature, I know, but the hand-to-hand struggle with her stimulates me. A painter can’t be great if he doesn’t understand landscape. At one point the term ‘landscapist’ was one of scorn, especially in the eighteenth century. And yet, that century which I adore produced great landscape artists. I am of the eighteenth century. I humbly consider not only that my art descends from Watteau, Fragonard, Hubert Robert, but even that I am one of them.’

As one recent scholar has noted of Renoir’s landscapes, ‘he skilfully realised the Impressionist notion of finding an adequate expression for the fleeting moment outdoors, defining the landscape in paintings and watercolours as an atmospheric colour appearance. Swift, open brushstrokes and vibrating colours create an urgent atmosphere of shimmering reflections of sunlight on the vegetation, water, and air. Particularly in his later works, Renoir returned to his Impressionist beginnings, creating pictures directly linked to certain seasons and times of day or specific places…He was inspired by the intensity of light in the Mediterranean and the lush vegetation in the South of France, where he spent the winter months from the late 1880s because of a severe case of rheumatism, before finally settling for good in Cagnes-sur-Mer in 1907. His late landscape compositions, for which the watercolour technique seemed ideally suited, are characterised by free and easy brushstrokes and a vivid as well as powerful use of colour.’

The present sheet is a fine and fresh example of Renoir’s watercolour technique as a landscapist, characterized by a freedom of handling and an assured use of colour. Landscape drawings such as this display ‘Renoir’s ability to suggest form simply by modulating his brushstrokes and colors…[and share] the autumnal greens, yellows, and russets of Renoir’s palette as well as the handling of foliage and careful pictorial organization.’ The artist here uses the white of the paper to capture the effect of bright sunlight, on which he applies delicate washes of green, red, yellow and blue to create both the forms and reflections of the trees and foliage.

Renoir’s watercolour landscapes of this type are generally dated between 1885 and 1900, and often show the influence of his close friend Paul Cézanne, whom he sometimes worked alongside. It has been suggested that some of the artist’s late watercolours may have once been part of an album or sketchbook of landscapes, inspired by the example of Cézanne, used by Renoir in the middle and late 1880s. As Richard Brettell has noted of another Cézannesque watercolour by Renoir, ‘Although the two painters are now considered virtual opposites, Auguste Renoir was probably Paul Cézanne’s closest friend during the thirty years before Cézanne died in 1906…And it was surely no accident that he turned to a medium that was more often Cézanne’s choice than his own…Renoir used [watercolour] to embrace Cézanne.’

This watercolour is recorded in the François Daulte archives at the Wildenstein Plattner Institute, and will be included in the forthcoming Renoir Digital Catalogue Raisonné. A certificate from the Wildenstein Plattner Institute, dated 19 October 2019, accompanies the present sheet.

As one recent scholar has noted of Renoir’s landscapes, ‘he skilfully realised the Impressionist notion of finding an adequate expression for the fleeting moment outdoors, defining the landscape in paintings and watercolours as an atmospheric colour appearance. Swift, open brushstrokes and vibrating colours create an urgent atmosphere of shimmering reflections of sunlight on the vegetation, water, and air. Particularly in his later works, Renoir returned to his Impressionist beginnings, creating pictures directly linked to certain seasons and times of day or specific places…He was inspired by the intensity of light in the Mediterranean and the lush vegetation in the South of France, where he spent the winter months from the late 1880s because of a severe case of rheumatism, before finally settling for good in Cagnes-sur-Mer in 1907. His late landscape compositions, for which the watercolour technique seemed ideally suited, are characterised by free and easy brushstrokes and a vivid as well as powerful use of colour.’

The present sheet is a fine and fresh example of Renoir’s watercolour technique as a landscapist, characterized by a freedom of handling and an assured use of colour. Landscape drawings such as this display ‘Renoir’s ability to suggest form simply by modulating his brushstrokes and colors…[and share] the autumnal greens, yellows, and russets of Renoir’s palette as well as the handling of foliage and careful pictorial organization.’ The artist here uses the white of the paper to capture the effect of bright sunlight, on which he applies delicate washes of green, red, yellow and blue to create both the forms and reflections of the trees and foliage.

Renoir’s watercolour landscapes of this type are generally dated between 1885 and 1900, and often show the influence of his close friend Paul Cézanne, whom he sometimes worked alongside. It has been suggested that some of the artist’s late watercolours may have once been part of an album or sketchbook of landscapes, inspired by the example of Cézanne, used by Renoir in the middle and late 1880s. As Richard Brettell has noted of another Cézannesque watercolour by Renoir, ‘Although the two painters are now considered virtual opposites, Auguste Renoir was probably Paul Cézanne’s closest friend during the thirty years before Cézanne died in 1906…And it was surely no accident that he turned to a medium that was more often Cézanne’s choice than his own…Renoir used [watercolour] to embrace Cézanne.’

This watercolour is recorded in the François Daulte archives at the Wildenstein Plattner Institute, and will be included in the forthcoming Renoir Digital Catalogue Raisonné. A certificate from the Wildenstein Plattner Institute, dated 19 October 2019, accompanies the present sheet.

Auguste Renoir was an inveterate draughtsman, equally adept in pencil, pen, chalk, charcoal, watercolour and pastel. Yet he seems to have thought little of his drawings, throwing away or destroying most of them, and is said to have even used drawings to light the kitchen stove. Apart from pastels, Renoir only rarely exhibited his drawings in his lifetime, and it was not until two years after his death that a significant exhibition of his drawings was held, at the Galerie Durand-Ruel in 1921. The exhibition comprised a large number of drawings, watercolours and pastels from all periods of the artist’s career, numbering almost 150 works. For many visitors, the exhibition was a revelation; as one critic wrote, ‘We make our way into the artist’s studio, he opens his portfolios for us, hides nothing from us, from the most accomplished works to the faintest of notes.’

For much of the last two decades of his life Renoir’s hands were crippled by arthritis, so that by around 1913 his hands were so bent that he was no longer able to draw. Yet it remains true of Renoir that, as François Daulte wrote, ‘It is in his sketches and studies, rather than his large paintings, that he reveals all his originality and freshness of vision.’

Provenance

Jean du Chatenet, Paris, unril 2003

Anonymous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 21 October 2003, lot 4

Andipa Gallery, London, in 2010

Stanley Michael Meyler, Evanston, Illinois.

Anonymous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 21 October 2003, lot 4

Andipa Gallery, London, in 2010

Stanley Michael Meyler, Evanston, Illinois.