Godfried MAES

(Antwerp 1649 - Antwerp 1700)

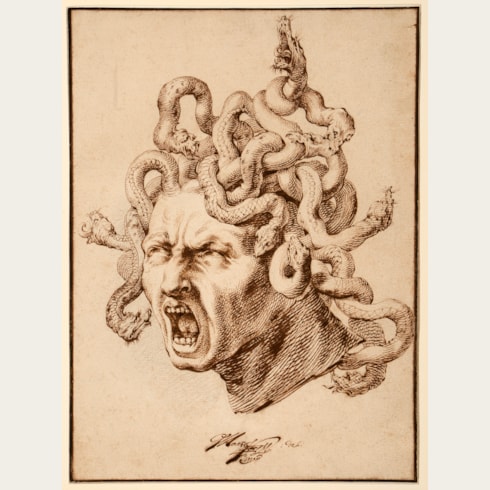

The Sisters of Phaeton Transformed into Poplars

Sold

Pen and brown ink and brown and gray wash, with framing lines in brown ink.

178 x 235 mm. (7 x 9 1/4 in.)

178 x 235 mm. (7 x 9 1/4 in.)

This drawing, the last in the series of four drawings by Godfried Maes, depicts Phaeton’s seven sisters, the Heliads, mourning the death of their brother, and being transformed into poplar trees:

‘Clymene, having uttered whatever can be uttered at such misfortune, grieving and frantic and tearing her breast, wandered over the whole earth first looking for her son’s limbs, and then failing that his bones. She found his bones already buried however, beside the riverbank in a foreign country. Falling to the ground she bathed with tears the name she could read on the cold stone and warmed it against her naked breast. The Heliads, her daughters and the Sun’s, cry no less, and offer their empty tribute of tears to the dead, and, beating their breasts with their hands, they call for their brother night and day, and lie down on his tomb, though he cannot hear their pitiful sighs.’

‘Four times the moon had joined her crescent horns to form her bright disc. They by habit, since use creates habit, devoted themselves to mourning. Then Phaethüsa, the eldest sister, when she tried to throw herself to the ground, complained that her ankles had stiffened, and when radiant Lampetia tried to come near her she was suddenly rooted to the spot. A third sister attempting to tear at her hair pulled out leaves. One cried out in pain that her legs were sheathed in wood, another that her arms had become long branches. While they wondered at this, bark closed round their thighs and by degrees over their waists, breasts, shoulders, and hands, and all that was left free were their mouths calling for their mother. What can their mother do but go here and there as the impulse takes her, pressing her lips to theirs where she can? It is no good. She tries to pull the bark from their bodies and break off new branches with her hands, but drops of blood are left behind like wounds. ‘Stop, mother, please’ cries out whichever one she hurts, ‘Please stop: It is my body in the tree you are tearing. Now, farewell.’ and the bark closed over her with her last words. Their tears still flow, and hardened by the sun, fall as amber from the virgin branches, to be taken by the bright river and sent onwards to adorn Roman brides.’

Perhaps intended as book illustrations or designs for prints, these highly refined drawings by Maes were never reproduced or published in his lifetime. In 1717 the artist’s widow sold all the drawings to the artist Jacob de Wit, who later used some of them as models for his own designs for illustrations, engraved under the supervision of Bernard Picart, for a 1732 translation of The Metamorphoses into Dutch, French and English editions. One of the Maes drawings that de Wit copied and adapted for the 1732 Metamorphoses was the present sheet of The Sisters of Phaeton Transformed into Poplars, which appears in reverse in the engraved illustration in the published book.

The original drawings by Godfried Maes remained together until 1762, when they were dispersed at auction in Amsterdam.

‘Clymene, having uttered whatever can be uttered at such misfortune, grieving and frantic and tearing her breast, wandered over the whole earth first looking for her son’s limbs, and then failing that his bones. She found his bones already buried however, beside the riverbank in a foreign country. Falling to the ground she bathed with tears the name she could read on the cold stone and warmed it against her naked breast. The Heliads, her daughters and the Sun’s, cry no less, and offer their empty tribute of tears to the dead, and, beating their breasts with their hands, they call for their brother night and day, and lie down on his tomb, though he cannot hear their pitiful sighs.’

‘Four times the moon had joined her crescent horns to form her bright disc. They by habit, since use creates habit, devoted themselves to mourning. Then Phaethüsa, the eldest sister, when she tried to throw herself to the ground, complained that her ankles had stiffened, and when radiant Lampetia tried to come near her she was suddenly rooted to the spot. A third sister attempting to tear at her hair pulled out leaves. One cried out in pain that her legs were sheathed in wood, another that her arms had become long branches. While they wondered at this, bark closed round their thighs and by degrees over their waists, breasts, shoulders, and hands, and all that was left free were their mouths calling for their mother. What can their mother do but go here and there as the impulse takes her, pressing her lips to theirs where she can? It is no good. She tries to pull the bark from their bodies and break off new branches with her hands, but drops of blood are left behind like wounds. ‘Stop, mother, please’ cries out whichever one she hurts, ‘Please stop: It is my body in the tree you are tearing. Now, farewell.’ and the bark closed over her with her last words. Their tears still flow, and hardened by the sun, fall as amber from the virgin branches, to be taken by the bright river and sent onwards to adorn Roman brides.’

Perhaps intended as book illustrations or designs for prints, these highly refined drawings by Maes were never reproduced or published in his lifetime. In 1717 the artist’s widow sold all the drawings to the artist Jacob de Wit, who later used some of them as models for his own designs for illustrations, engraved under the supervision of Bernard Picart, for a 1732 translation of The Metamorphoses into Dutch, French and English editions. One of the Maes drawings that de Wit copied and adapted for the 1732 Metamorphoses was the present sheet of The Sisters of Phaeton Transformed into Poplars, which appears in reverse in the engraved illustration in the published book.

The original drawings by Godfried Maes remained together until 1762, when they were dispersed at auction in Amsterdam.

The Flemish painter and draughtsman Gotfried Maes studied in his native Antwerp with his father and with the painter Pieter van Lint. He was admitted to the painter’s guild in Antwerp in 1672, becoming dean of the guild ten years later. He spent his entire career in Antwerp, receiving commissions for altarpieces and history paintings from churches and collectors in Antwerp, Brussels and Liège. Much of his work is in a grand scale, such as a large altarpiece of The Martyrdom of Saint George, painted in 1681 for the Antwerp church of St. Joris and today in the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten in Antwerp, and Maes may be regarded as among the last of the Flemish Baroque artists. Among his important patrons was Eugen Alexander Franz, Prince of Thurn and Taxis, for whose palace in Brussels he painted an allegorical ceiling painting glorifying the Thurn and Taxis family. Maes worked as a designer of tapestry cartoons, often in collaboration with the tapestry workshop of Urbanus Leyniers in Brussels, and also produced book illustrations and a number of etchings. One of his last major decorative projects was the ceiling decoration of the Palace of Coudenberg in Brussels for the governor of the Spanish Netherlands, Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria; on which he worked between 1697 and 1700.

A gifted draughtsman, Maes produced numerous drawings, both as preparatory studies for paintings and as finished, independent works. Arguably the most significant example of the latter group are a series of 83 elaborate pen and wash drawings illustrating various episodes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Perhaps intended as book illustrations or designs for prints, these refined drawings were, however, never reproduced or published in his lifetime. In 1717 the artist’s widow sold all the drawings to the art dealer Jacob de Wit, and they were eventually used as illustrations for a 1732 translation of the Metamorphoses into French. The original drawings by Maes remained together until 1762, when they were dispersed at auction in Amsterdam.

Drawings by Maes are today in the collections of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Musea Brugge in Bruges, the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum in Cologne, the Hessisches Landesmuseum in Darmstadt, the Hamburger Kunsthalle in Hamburg, the British Museum in London, the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, the University Library in Leiden, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Louvre and the Fondation Custodia in Paris, the Museum Boijmans-van Beuningen in Rotterdam, the Eesti Kunstimuuseum in Tallinn, the Biblioteca Reale in Turin, the Albertina in Vienna, and elsewhere.

Provenance

Part of a series of eighty-three drawings of scenes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses with provenance as follows

The artist’s widow, Josina Baeckelandt, Antwerp

Sold by her, sometime before 1717, for 800 florins to Jacob de Wit, Amsterdam

His posthumous sale, Amsterdam, de Leth, 10 March 1755 onwards, in Kunstboek U (‘Waarïn de Herscheppingen van Ovidius, in Drieëntagtig uitvoerige Teekeningen, door G. Maas. Welke in één koop verkocht zullen worden.’, bt. Cronenburgh)

B. Cronenburgh, Amsterdam

His posthumous sale, Amsterdam, de Leth, 22-25 March 1762, portfolio A, no.1 (‘Drie-en-tachentig Teekeningen uit de Ovidius, alle zeer uitvoerig met Oost-Indische Inkt geteekend door G. Maas, en een weinigje geretoucheerd door J. de Wit.’)

The drawings thereafter divided

Possibly Graaf van Neale, Amsterdam(?)

Possibly his posthumous sale, Amsterdam, de Winter Zweertz, 28 March 1774 onwards, Portfolio 1, lot 542

Anonymous sale, Amsterdam, Mak van Waay, 15 January 1974, part of lot 1273 (‘Dertig tekeningen met voorstellingen van mythologische scenes o.a. betrekking hebbend op Ovidius’ Metamorfosen’, bt. Dreesmann)

Anton C.R. Dreesmann, Amsterdam

His posthumous sale, London, Christie’s, 11 April 2002, part of lot 666

Thomas Williams Fine Art Ltd., London, in 2003

Private collection.

The artist’s widow, Josina Baeckelandt, Antwerp

Sold by her, sometime before 1717, for 800 florins to Jacob de Wit, Amsterdam

His posthumous sale, Amsterdam, de Leth, 10 March 1755 onwards, in Kunstboek U (‘Waarïn de Herscheppingen van Ovidius, in Drieëntagtig uitvoerige Teekeningen, door G. Maas. Welke in één koop verkocht zullen worden.’, bt. Cronenburgh)

B. Cronenburgh, Amsterdam

His posthumous sale, Amsterdam, de Leth, 22-25 March 1762, portfolio A, no.1 (‘Drie-en-tachentig Teekeningen uit de Ovidius, alle zeer uitvoerig met Oost-Indische Inkt geteekend door G. Maas, en een weinigje geretoucheerd door J. de Wit.’)

The drawings thereafter divided

Possibly Graaf van Neale, Amsterdam(?)

Possibly his posthumous sale, Amsterdam, de Winter Zweertz, 28 March 1774 onwards, Portfolio 1, lot 542

Anonymous sale, Amsterdam, Mak van Waay, 15 January 1974, part of lot 1273 (‘Dertig tekeningen met voorstellingen van mythologische scenes o.a. betrekking hebbend op Ovidius’ Metamorfosen’, bt. Dreesmann)

Anton C.R. Dreesmann, Amsterdam

His posthumous sale, London, Christie’s, 11 April 2002, part of lot 666

Thomas Williams Fine Art Ltd., London, in 2003

Private collection.

Literature

J. van Tatenhove, ‘Tekeningen door Jacob de Wit voor de Ovidius van Picart’, Leids Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 1985: Achttiende-Eeuwse Kunst in de Nederlanden, 1987, p.225 and p.233, note 40; The Burlington Magazine, March 2003, unpaginated [advertisement]; Clifford S. Ackley, ‘The Intuitive Eye: Drawings and Paintings from the Collection of Horace Wood Brock’, in Horace Wood Brock, Martin P. Levy and Clifford S. Ackley, Splendor and Elegance: European Decorative Arts and Drawings from the Horace Wood Brock Collection, exhibition catalogue, Boston, 2009, p.97 and p.158, no.136, illustrated p.133; Victoria Sancho Lobis, Rubens, Rembrandt and Drawing in the Golden Age, exhibition catalogue, Chicago, 2019-2020, p.283, note 6.

Exhibition

Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Splendor and Elegance: European Decorative Arts and Drawings from the Horace Wood Brock Collection, 2009, no.136.