Jean-Baptiste GREUZE

(Tournus 1725 - Paris 1805)

Studies of Three Hands

Sold

Red chalk, with framing lines in brown ink, laid down on a 19th century mount.

Inscribed Greuze at the lower left, and further inscribed Greuze (jean baptiste) on the mount.

315 x 492 mm. (12 3/8 x 19 3/8 in.)

Inscribed Greuze at the lower left, and further inscribed Greuze (jean baptiste) on the mount.

315 x 492 mm. (12 3/8 x 19 3/8 in.)

The inventory of Jean-Baptiste Greuze’s property taken during his divorce proceedings mentions eighty-one studies of hands and feet by the artist, kept in his studio. As Irina Novosselskaya has noted, ‘Drawings constituted a special place in Greuze’s work. Without exaggeration it can be said that no other eighteenth-century French artist made so many careful studies for his paintings…Greuze’s sketches, often done in different tones of red chalk, are almost always done on large sheets (40 to 50 centimetres high), and they almost always depict figures, heads, and hands in large scale. Strong, bold strokes produce forms and portray movement...The artist was constantly searching for the correct placement or movement of hands.’ Furthermore, as the Greuze scholar Edgar Munhall has pointed out, ‘The attention that Greuze devoted to hands in general…and the skill with which he drew them suggests the importance he attached to them as expressive elements secondary only to faces and gestures in conveying the meaning of his dramatic scenes.’

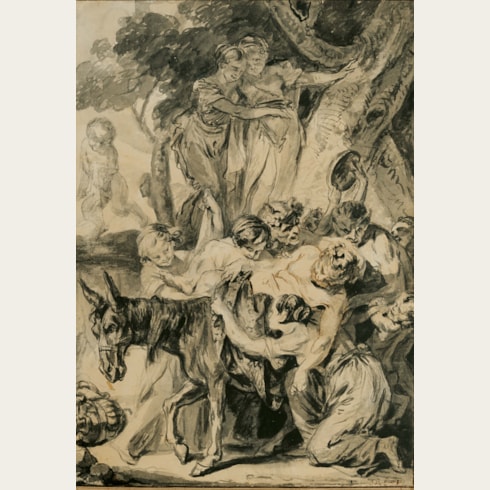

All three studies of hands on this large sheet are preparatory for Greuze’s large painting The Hermit, or The Distributor of Rosaries (Le donneur de chapelets) of c.1780, sold at auction in 2013 and today in a private collection. The scene is set in a hermit’s grotto dominated by a crucifix where ‘a stern old Franciscan friar encircles the left hand of a reverent young woman in white with the first from a chest full of red rosaries. Brightly lit and standing in the center of the composition, she is the culminating cross in a living rosary of girls linked by limbs enacting extravagant expressions of emotion and affection. To enrich the contrast of male and female, youth and age, Greuze has added an epicene assistant holding the chest for the hoary-headed monk. That novice is as pretty as the young women from whom his pure and modest gaze is wholly averted.’

The large painting was probably commissioned from Greuze by its first recorded owner, Louis Gabriel, Marquis de Véri, who owned several other important paintings by the artist. As Pierre Rosenberg has noted of The Hermit, ‘Beyond the genre aspect, there is…a juxtaposition of contrasts – the happiness of innocent childhood and the simple joys of adolescence with the harsh wisdom of old age – which transcends the simple anecdote.’ A reproductive print after the painting, engraved by Henri Marais, was published in Paris in 1788.

The right arm and hand at the upper right of the present sheet is a study for the figure of a young girl in the centre of the composition of the painting, while the two other studies of hands were used for the kneeling girl in a red dress in the foreground. A closely comparable drawing by Greuze of four arms and hands, today in the Musée Bonnat-Helleu in Bayonne, contains studies for the left arm of the central figure and the hands of the two girls next to her.

Other preparatory studies by Greuze for The Hermit, or The Distributor of Rosaries include a large red chalk drawing for the figure of the hermit in the Louvre and a study for the feet of the kneeling acolyte at the lower right, in the Musée Bonnat-Helleu in Bayonne. A large but somewhat sketchy red chalk study for the two little girls in white behind the central figure was, like the present sheet, once in the collection of Jean Masson, while a study in red chalk for the head of the girl holding a chicken, at the left of centre of the composition, appeared at auction in Paris in 1999.

Further drawings of hands by Greuze are today in the collections of the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas in Austin, the Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie in Besançon, the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven and the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, as well as one example formerly in the Curtis Baer collection.

The present sheet bears the collector’s mark of Jean Masson (1856-1933), who owned a considerable number of drawings by Greuze. Masson gave much of his extensive collection of ornamental drawings and prints to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. His superb collection of 18th century French master drawings, however, was dispersed at several auctions in Paris between 1923 and 1927.

All three studies of hands on this large sheet are preparatory for Greuze’s large painting The Hermit, or The Distributor of Rosaries (Le donneur de chapelets) of c.1780, sold at auction in 2013 and today in a private collection. The scene is set in a hermit’s grotto dominated by a crucifix where ‘a stern old Franciscan friar encircles the left hand of a reverent young woman in white with the first from a chest full of red rosaries. Brightly lit and standing in the center of the composition, she is the culminating cross in a living rosary of girls linked by limbs enacting extravagant expressions of emotion and affection. To enrich the contrast of male and female, youth and age, Greuze has added an epicene assistant holding the chest for the hoary-headed monk. That novice is as pretty as the young women from whom his pure and modest gaze is wholly averted.’

The large painting was probably commissioned from Greuze by its first recorded owner, Louis Gabriel, Marquis de Véri, who owned several other important paintings by the artist. As Pierre Rosenberg has noted of The Hermit, ‘Beyond the genre aspect, there is…a juxtaposition of contrasts – the happiness of innocent childhood and the simple joys of adolescence with the harsh wisdom of old age – which transcends the simple anecdote.’ A reproductive print after the painting, engraved by Henri Marais, was published in Paris in 1788.

The right arm and hand at the upper right of the present sheet is a study for the figure of a young girl in the centre of the composition of the painting, while the two other studies of hands were used for the kneeling girl in a red dress in the foreground. A closely comparable drawing by Greuze of four arms and hands, today in the Musée Bonnat-Helleu in Bayonne, contains studies for the left arm of the central figure and the hands of the two girls next to her.

Other preparatory studies by Greuze for The Hermit, or The Distributor of Rosaries include a large red chalk drawing for the figure of the hermit in the Louvre and a study for the feet of the kneeling acolyte at the lower right, in the Musée Bonnat-Helleu in Bayonne. A large but somewhat sketchy red chalk study for the two little girls in white behind the central figure was, like the present sheet, once in the collection of Jean Masson, while a study in red chalk for the head of the girl holding a chicken, at the left of centre of the composition, appeared at auction in Paris in 1999.

Further drawings of hands by Greuze are today in the collections of the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas in Austin, the Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie in Besançon, the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven and the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, as well as one example formerly in the Curtis Baer collection.

The present sheet bears the collector’s mark of Jean Masson (1856-1933), who owned a considerable number of drawings by Greuze. Masson gave much of his extensive collection of ornamental drawings and prints to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. His superb collection of 18th century French master drawings, however, was dispersed at several auctions in Paris between 1923 and 1927.

Following a period of study in Lyon, Jean-Baptiste Greuze arrived in Paris sometime in the early 1750s and began studying drawing with Charles-Joseph Natoire and Louis de Sylvestre. Very little is known of the artist’s early Parisian period, however. He was admitted into the Académie Royale as an associate member in 1755, in the category of peintre de genre particulier, and the same year exhibited several works at the Salon with some success, with three of the paintings acquired by the influential collector Ange Laurent de La Live de Jully. (Greuze did not, however, supply a morceau de recéption to the Académie, which was required in order to gain full membership as an Academician, until 1769.) In September 1755 the young artist travelled to Italy with another influential patron, the Abbé Gougenot, and he worked in Rome, mainly on portrait commissions and genre paintings, until the spring of 1757. Greuze’s paintings of moralizing genre subjects, exhibited at the biennial Salons from 1761, earned him the praise of the influential critic Denis Diderot. He was also a fine portraitist, exhibiting a number of portraits at the Salon throughout the 1760s to considerable acclaim.

While Greuze enjoyed the patronage of such prominent collectors as La Live de Jully, Madame de Pompadour and her brother, the Marquis de Marigny, Jean de Jullienne, the Duc de Choiseul and the Empress Catherine II of Russia, his difficult temperament often alienated other clients. (Indeed, even the artist’s great champion Diderot, writing to the sculptor Etienne Falconet in 1767, described Greuze as ‘an excellent artist but a bad-tempered fellow. One should collect his drawings and his pictures and otherwise leave him alone.’) Notwithstanding his success as a painter of genre subjects and portraits, Greuze always aspired to be recognized as a history painter. Throughout the 1760s he had considered various themes for his long-overdue morceau de reception for the Académie Royale, which he wanted to be of a mythological, Biblical or historical subject. In 1769, some fourteen years after he was agrée at the Académie, he finally submitted a painting of Septimus Severus Reproaching Caracalla as his reception piece. However, the work was rejected by the Académie, who instead admitted the artist only as a genre painter. Angered and humiliated by this snub, Greuze henceforth refused to exhibit at the Salons, choosing instead to show his paintings in his studio in the Louvre, where they attracted a good deal of public interest. He continued to enjoy considerable success throughout the 1770s and 1780s, especially among Russian patrons, and also profited from the sale of prints after his works. His reputation began to suffer in the years after the Revolution and with the rise of Neoclassicism, although by 1800 he had returned to exhibiting his works at the Salon, after an absence of thirty-one years, and continued to do so until 1804, when among the works he showed was a fine self-portrait. Greuze died, in his studio, at the age of nearly eighty, and was buried in the cemetery of Montmartre.

Greuze was a gifted and versatile draughtsman, equally adept in chalk, pastel and ink. From 1757 onwards he regularly showed finished drawings as well as oil paintings at the Salons, and one critic, writing of the 1761 exhibition, noted ‘Several drawings by M. Greuze...do him as much honour by their execution as by the choice and genius of their invention.’ The artist’s drawings were also often praised by Diderot, who noted that ‘this man draws like an angel…He is enthusiastic about his art: he makes endless studies; he spares neither care nor expenses in order to have the models that suit him.’ Greuze produced many preparatory studies, including compositional studies in pen and ink and head, hand and figure studies in chalk, for each of his painted compositions. A particular interest was the study of physiognomy and facial expression, made manifest through large-scale drawings of têtes d’expression. These drawings of heads, usually in red chalk, allowed the artist to refine the facial types and expressions that were such an important part of his paintings, but they were also produced as independent works of art, to be sold to collectors. Indeed, Greuze enjoyed a healthy market for his finished drawings; as the 18th century collector and connoisseur Pierre-Jean Mariette noted of him, ‘Il a fait aussi nombre de desseins, qui, dans le commencement, lui ont été payés prodigieusement par quelque curieux.’ Greuze’s drawings found their way into important 18th century collections in France, Russia and Germany, while several fellow artists, including Aignan-Thomas Desfriches, Claude Hoin, Joseph-Marie Vien and Johann Georg Wille, owned drawings by him.

While Greuze enjoyed the patronage of such prominent collectors as La Live de Jully, Madame de Pompadour and her brother, the Marquis de Marigny, Jean de Jullienne, the Duc de Choiseul and the Empress Catherine II of Russia, his difficult temperament often alienated other clients. (Indeed, even the artist’s great champion Diderot, writing to the sculptor Etienne Falconet in 1767, described Greuze as ‘an excellent artist but a bad-tempered fellow. One should collect his drawings and his pictures and otherwise leave him alone.’) Notwithstanding his success as a painter of genre subjects and portraits, Greuze always aspired to be recognized as a history painter. Throughout the 1760s he had considered various themes for his long-overdue morceau de reception for the Académie Royale, which he wanted to be of a mythological, Biblical or historical subject. In 1769, some fourteen years after he was agrée at the Académie, he finally submitted a painting of Septimus Severus Reproaching Caracalla as his reception piece. However, the work was rejected by the Académie, who instead admitted the artist only as a genre painter. Angered and humiliated by this snub, Greuze henceforth refused to exhibit at the Salons, choosing instead to show his paintings in his studio in the Louvre, where they attracted a good deal of public interest. He continued to enjoy considerable success throughout the 1770s and 1780s, especially among Russian patrons, and also profited from the sale of prints after his works. His reputation began to suffer in the years after the Revolution and with the rise of Neoclassicism, although by 1800 he had returned to exhibiting his works at the Salon, after an absence of thirty-one years, and continued to do so until 1804, when among the works he showed was a fine self-portrait. Greuze died, in his studio, at the age of nearly eighty, and was buried in the cemetery of Montmartre.

Greuze was a gifted and versatile draughtsman, equally adept in chalk, pastel and ink. From 1757 onwards he regularly showed finished drawings as well as oil paintings at the Salons, and one critic, writing of the 1761 exhibition, noted ‘Several drawings by M. Greuze...do him as much honour by their execution as by the choice and genius of their invention.’ The artist’s drawings were also often praised by Diderot, who noted that ‘this man draws like an angel…He is enthusiastic about his art: he makes endless studies; he spares neither care nor expenses in order to have the models that suit him.’ Greuze produced many preparatory studies, including compositional studies in pen and ink and head, hand and figure studies in chalk, for each of his painted compositions. A particular interest was the study of physiognomy and facial expression, made manifest through large-scale drawings of têtes d’expression. These drawings of heads, usually in red chalk, allowed the artist to refine the facial types and expressions that were such an important part of his paintings, but they were also produced as independent works of art, to be sold to collectors. Indeed, Greuze enjoyed a healthy market for his finished drawings; as the 18th century collector and connoisseur Pierre-Jean Mariette noted of him, ‘Il a fait aussi nombre de desseins, qui, dans le commencement, lui ont été payés prodigieusement par quelque curieux.’ Greuze’s drawings found their way into important 18th century collections in France, Russia and Germany, while several fellow artists, including Aignan-Thomas Desfriches, Claude Hoin, Joseph-Marie Vien and Johann Georg Wille, owned drawings by him.

Provenance

Jean Masson, Amiens and Paris (Lugt 1494a)

His sale, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, 6 December 1923, lot 57 (‘Feuille de trois études de mains. Sanguine. Haut., 31 cent. 5; larg., 49 cent. 2’)

Private collection, France.

His sale, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, 6 December 1923, lot 57 (‘Feuille de trois études de mains. Sanguine. Haut., 31 cent. 5; larg., 49 cent. 2’)

Private collection, France.

Literature

Possibly J. Martin and Ch. Masson, 'Catalogue raisonné de l'œuvre peint et dessiné de Jean-Baptiste Greuze', in Camille Mauclair, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Paris, n.d. [1905?], possibly no.1423 (‘Mains. Sanguine. – Étude de bras et de mains de femme. Vente Walferdin, en 1860.’); Mehdi Korchane et al, Le Trait et l’Ombre: Dessins français du musée des Beaux-Arts d’Orléans, exhibition catalogue, Sceaux, 2022, p.186, under no.72.