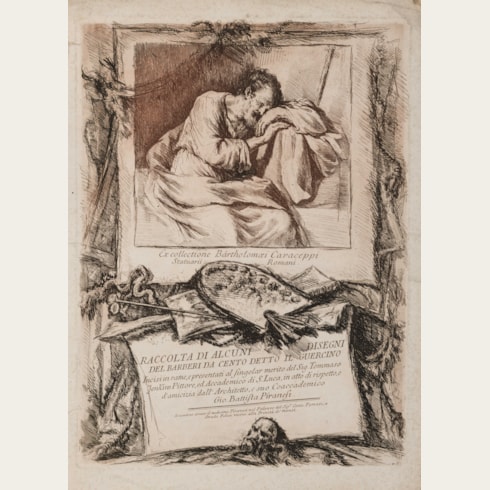

Giovanni Battista PIRANESI

(Mogliano 1720 - Venice 1778)

A Standing Man with One Knee Resting on a Ledge

Pen and brown ink, with traces of red chalk (possibly offset from another sheet).

A series of mathematical computations, probably in the artist's hand, in brown ink on the verso.

146 x 125 mm. (5 3/4 x 4 7/8 in.)

A series of mathematical computations, probably in the artist's hand, in brown ink on the verso.

146 x 125 mm. (5 3/4 x 4 7/8 in.)

In one of the first studies of Giambattista Piranesi as a draughtsman, Hylton Thomas noted that ‘Piranesi’s drawings are one of the unexpected delights inherited by us from that age of enchantment, the eighteenth century…they reveal clearly the qualities which have aroused present-day interest on the part of collectors and connoisseurs – inventiveness in subject; freshness, brilliance, and colour; dynamic energy. In them can be felt, often more vividly than in his prints, the impact of one of the most unusual and provocative among eighteenth-century artists.’

More recently, David Rosand has written of Piranesi that, ‘From rapid sketches set down with impulsive energy to the most deliberately finished architectural renderings, he demonstrated a control of graphic media that was confident and exploratory, precise and yet open, and always suggestive. Piranesi’s was a fundamentally graphic imagination. He thought with pen, chalk or etching needle in hand, considering his activity on the grounded copperplate to be the same as drawing on paper.’

Although Piranesi was a prolific draughtsman, figure studies account for a relatively small portion of his output. These spirited, spontaneous studies of figures in animated movement, often drawn on the verso of proof impressions of his engravings, were done to study a pose or gesture. Executed with rapid strokes of pen and ink or chalk, these drawings give little, if any, indication of a setting or background. As Thomas has written, ‘The figure-studies constitute one of Piranesi’s most enjoyable types of drawing…all are extremely free notations of men, and occasionally women and children, caught in full and momentary movement…Some of the pen and ink sketches were probably drawn from memory, but others must have been drawn in his studio, using assistants as models…Whether in chalk or ink, the figures share one very notable trait – they are studies of movement. The human figure in action, rather than the human bodyper se, fascinated Piranesi. He built up dynamic masses of energy primarily by means of areas of parallel shading within the body, which is given strong direction in space by pose and jagged contours.’

While similar figures often appear in Piranesi’s prints, where they are used to show the scale of the monuments, only rarely are the figure drawings directly related to the prints. As such, it is difficult to date such figure studies within the artist’s oeuvre, although most appear to date from after 1755, and they become fewer in number after about 1770. The freedom and expressiveness of Piranesi’s figure drawings, as well as their seeming spontaneity and economy of handling, has led some in the past to be mistakenly attributed to Francesco Guardi and, particularly for the chalk drawings, Antoine Watteau.

Significant examples of figure drawings by Piranesi are today in the collections of the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin, the British Museum in London, the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, the Louvre and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, and elsewhere.

The present sheet bears the collector’s mark of the French marchand-amateurJacques Petithory (1929-1992), who dealt in Old Master drawings from a stall at the Marché aux Puces in Paris from the mid-1950s onwards. At his death in 1992 Petithory (or Petit-Hory) left much of his interesting and eclectic collection of mainly Italian and French drawings, numbering 186 sheets, together with paintings, sculptures, ceramics and other objets d’art,to the Musée Bonnat (now the Musée Bonnat-Helleu) in Bayonne.

More recently, David Rosand has written of Piranesi that, ‘From rapid sketches set down with impulsive energy to the most deliberately finished architectural renderings, he demonstrated a control of graphic media that was confident and exploratory, precise and yet open, and always suggestive. Piranesi’s was a fundamentally graphic imagination. He thought with pen, chalk or etching needle in hand, considering his activity on the grounded copperplate to be the same as drawing on paper.’

Although Piranesi was a prolific draughtsman, figure studies account for a relatively small portion of his output. These spirited, spontaneous studies of figures in animated movement, often drawn on the verso of proof impressions of his engravings, were done to study a pose or gesture. Executed with rapid strokes of pen and ink or chalk, these drawings give little, if any, indication of a setting or background. As Thomas has written, ‘The figure-studies constitute one of Piranesi’s most enjoyable types of drawing…all are extremely free notations of men, and occasionally women and children, caught in full and momentary movement…Some of the pen and ink sketches were probably drawn from memory, but others must have been drawn in his studio, using assistants as models…Whether in chalk or ink, the figures share one very notable trait – they are studies of movement. The human figure in action, rather than the human bodyper se, fascinated Piranesi. He built up dynamic masses of energy primarily by means of areas of parallel shading within the body, which is given strong direction in space by pose and jagged contours.’

While similar figures often appear in Piranesi’s prints, where they are used to show the scale of the monuments, only rarely are the figure drawings directly related to the prints. As such, it is difficult to date such figure studies within the artist’s oeuvre, although most appear to date from after 1755, and they become fewer in number after about 1770. The freedom and expressiveness of Piranesi’s figure drawings, as well as their seeming spontaneity and economy of handling, has led some in the past to be mistakenly attributed to Francesco Guardi and, particularly for the chalk drawings, Antoine Watteau.

Significant examples of figure drawings by Piranesi are today in the collections of the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin, the British Museum in London, the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, the Louvre and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, and elsewhere.

The present sheet bears the collector’s mark of the French marchand-amateurJacques Petithory (1929-1992), who dealt in Old Master drawings from a stall at the Marché aux Puces in Paris from the mid-1950s onwards. At his death in 1992 Petithory (or Petit-Hory) left much of his interesting and eclectic collection of mainly Italian and French drawings, numbering 186 sheets, together with paintings, sculptures, ceramics and other objets d’art,to the Musée Bonnat (now the Musée Bonnat-Helleu) in Bayonne.

From his first visit to Rome in 1740, Giambattista Piranesi was interested in architecture and stage design, which he had studied in the studio of Domenico and Giuseppe Valeriani. By 1743 he had settled in Rome, and that year published etchings of several of his architectural designs as the Prima parte de architetture e prospettive, in which he adapted antique Roman forms into a modern, more unrestrained idiom, partly inspired by his early interest in stage design. Piranesi’s most celebrated works, the Le carceri (1743-1746) and Le antichita romane (1756) came soon afterwards. With the accession of the Venetian Carlo Rezzonico to the papacy as Pope Clement XIII in 1758, Piranesi was at last able to put some of his architectural theories to practice. The papal court provided important commissions to Venetian artists, chief among them Piranesi. In 1764 he was commissioned by the Pope’s nephew, Cardinal Giovanni Battista Rezzonico, to oversee the restoration of the church of Santa Maria del Priorato on the Aventine hill, and at around the same time was asked to draw up plans for the rebuilding of the west end of the Basilica of San Giovanni Laterano. His last years were spent making drawings of the antiquities discovered at Pompeii and Herculaneum, some of which were later engraved by his son Francesco.

Provenance

Jacques Petithory, Levallois-Perret (Lugt 4138)

Artemis Fine Arts, London, in 1993

Trinity Fine Art, London, in 1994

Artur Ramon, Barcelona, in 1996

Anonymous sale, New York, Sotheby’s, 26 January 2000, lot 77

Anonymous sale, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, 19 June 2003, lot 24

Gérard Lhéritier (Aristophil), Nice.

Artemis Fine Arts, London, in 1993

Trinity Fine Art, London, in 1994

Artur Ramon, Barcelona, in 1996

Anonymous sale, New York, Sotheby’s, 26 January 2000, lot 77

Anonymous sale, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, 19 June 2003, lot 24

Gérard Lhéritier (Aristophil), Nice.

Literature

London, Trinity Fine Art, Old Master Drawings and European Works of Art, exhibition catalogue, New York, 1994, pp.58-59, no.26; Barcelona, Sala d’Art Artur Ramon, Raíz del Arte II: Una exposición de dibujos antiguos (Siglos XVI al XIX), exhibition catalogue, 1996, pp.56-59, no.11; Linda Wolk-Simon and Carmen C. Bambach, An Italian Journey. Drawings from the Tobey Collection: Correggio to Tiepolo, exhibition catalogue, New York, 2010, p.219, under no.69, fig.69.1 (as whereabouts unknown).

Exhibition

New York, Trinity Fine Art at Newhouse Galleries, An Exhibition of Old Master Drawings and European Works of Art, 1994, no.26; Barcelona, Sala d’Art Artur Ramon, Raíz del Arte II: Una exposición de dibujos antiguos (Siglos XVI al XIX), 1996, no.11.