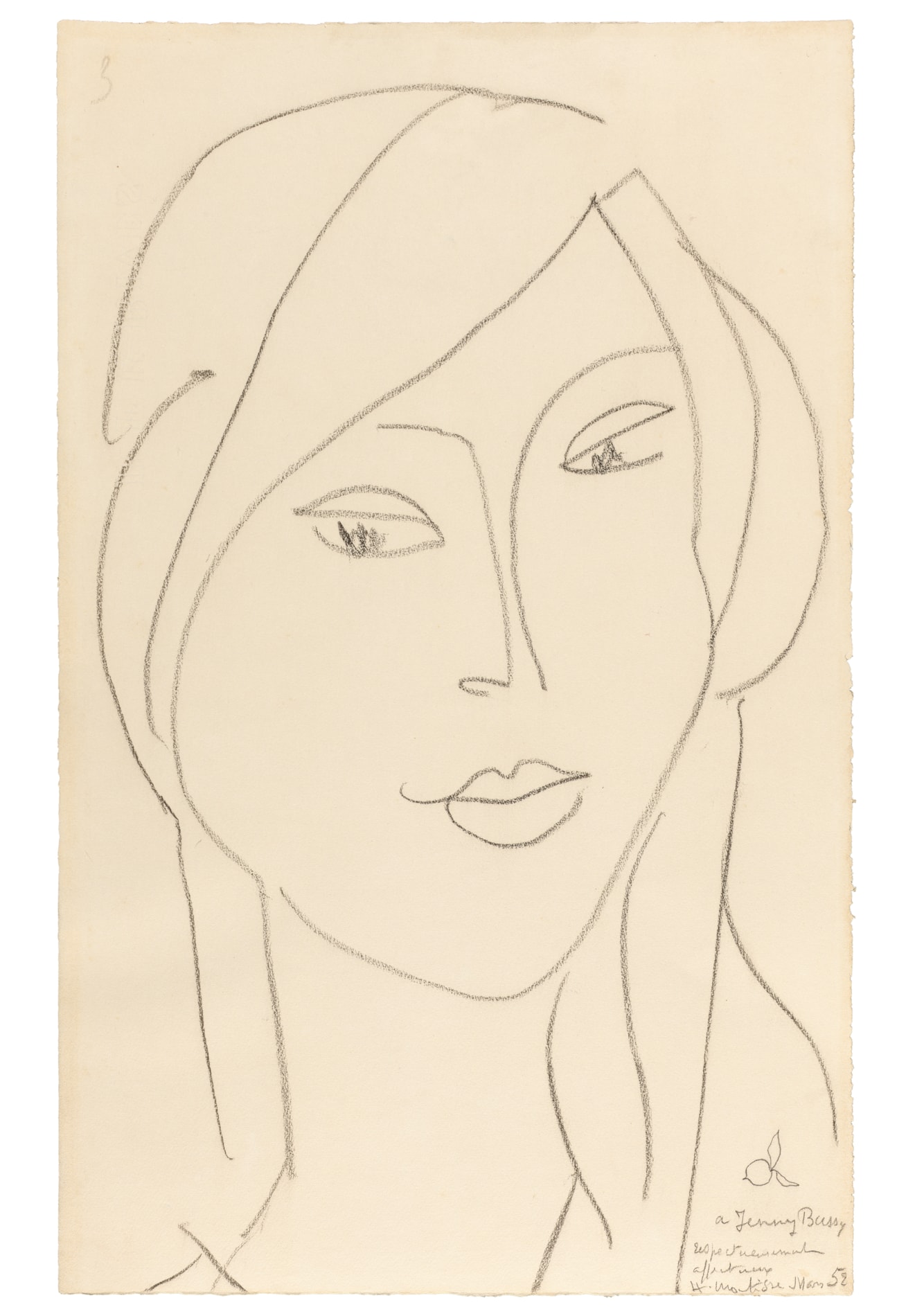

Henri MATISSE

(Le Cateau-Cambrésis 1869 - Nice 1964)

Portrait of Janie Bussy

Sold

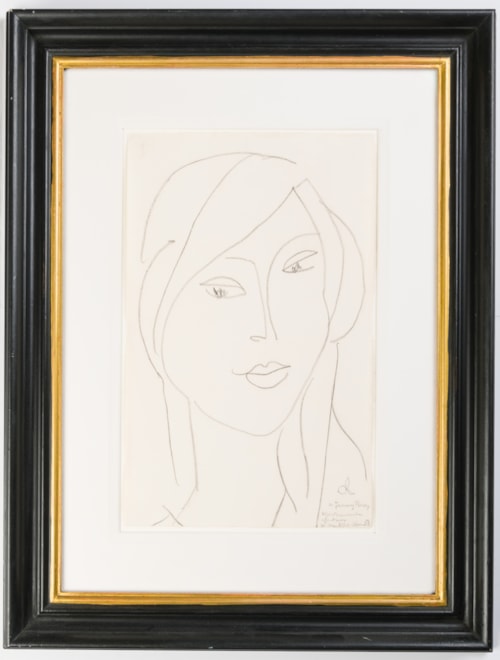

Black chalk on paper, laid down on board.

Signed, dated and dedicated 'a Jenny Bussy / respecteusement / affectueux / H. Matisse Mars 52' at the lower right.

Numbered 3 in pencil at the upper left.

457 x 286 mm. (18 x 11 1/4 in.)

Signed, dated and dedicated 'a Jenny Bussy / respecteusement / affectueux / H. Matisse Mars 52' at the lower right.

Numbered 3 in pencil at the upper left.

457 x 286 mm. (18 x 11 1/4 in.)

Drawn in 1950 and presented to the sitter two years later, this portrait drawing depicts Janie Bussy, the daughter of one of Matisse’s oldest and dearest friends, the artist Simon Bussy. The sitter, Jane Simone Bussy (1906-1960) was the only child of Simon Bussy and Dorothy Strachey, the sister of Lytton Strachey. Her father and Matisse had been fellow students in the atelier of Gustave Moreau in the 1890s, and maintained a lifelong friendship. Living in Nice and Cimiez, Matisse was a near neighbour of the Bussy family, who lived at Roquebrune, and came weekly to visit, so that the young Janie Bussy grew up seeing much of the master. As Matisse’s biographer Hilary Spurling has noted, however, ‘Janie, positioned like her parents between England and France, grew up among some of the finest minds and keenest gossips of both countries…[she] spent much time as a teenager in the company of adults who revered Matisse...but she herself has sucked in a healthy dose of Strachey scepticism and satirical dissent with her mother’s milk.’

Janie Bussy appears to have regarded Matisse as a somewhat pompous figure, and was envious of the time that her father spent with him. As Spurling has written, ‘Bussy’s wife and daughter…were increasingly exasperated by the amount of time Simon spent apparently dancing attendance on his prosperous old friend. Janie especially resented the contrast between Matisse’s international standing and her father’s poverty and obscurity (“She was jealous on her father’s behalf,” Lydia [Delectorskaya] said in retrospect: “Matisse was perfectly aware of the hostility felt for him by Bussy’s daughter, but he discounted it because he felt it came from wounded pride at her father’s lack of success”)…Janie, whose wit, intellect, and erudition could have made her an outstanding scholar, produced instead mild, unassertive paintings of landscapes and flowers. Both [she and her mother] amused themselves by including an ironic, mocking, mercilessly entertaining commentary on Matisse’s latest doings in their voluminous correspondence with some of the finest minds and best gossips in London and Paris.’ In 1947 Janie Bussy wrote a highly satirical memoir of Matisse, entitled ‘A Great Man’, which was read to a meeting of the ‘Memoir Club’ in Bloomsbury that year, but remained unpublished until 1986.

Perhaps not surprisingly, ‘Matisse respected Mme [Dorothy] Bussy’s cultivated mind and critical acumen, but he never felt comfortable in her company or her daughter’s. He showed up at her tea table for Simon’s sake, making solemn small talk and wearing the reddish-brown tweed suit he kept for polite occasions of this sort.’ Nevertheless, there seems to be no trace of any animosity in this affectionate portrait by Matisse of Janie Bussy, who was, like her father, a painter, and exhibited her landscapes and still life paintings at the Lefevre Gallery in London. Among stylistically comparable late portrait drawings by Matisse are a suite of ten studies of the head of his granddaughter Jacqueline, drawn in 1947 and similarly imbued with a certain intimacy; two of these drawings are in the Musée Nationale d’Art Moderne in Paris and the rest are in a private collection.

As Matisse described his approach to making portrait drawings, ‘I find myself before a person who interests me and, pencil or charcoal in hand, I set down his appearance on the paper, more or less freely. This…permits me to give free rein to my faculties of observation. At that moment, it wouldn’t do to ask a specific question, even a banal one such as ‘What time is it?’ because my reverie, my meditation upon the model, would be broken, and the result of my effort would be seriously compromised. After half-an-hour or an hour I am surprised to see a more or less precise image, which resembles the person with whom I am in contact, gradually appear on my paper. The image is revealed to me as though each stroke of charcoal erased from the glass some of the mist which until then had prevented me from seeing it.’

The present sheet displays the confident draughtsmanship of Matisse even in old age. It is among the very few independent drawings from the 1950s, a period when the artist was often bedridden with illness, and was focusing much of his energy on the seminal series of paper cut-outs that made up his final significant artistic endeavour. When he made drawings, he sometimes did so from his bed, using a long stick of bamboo with a brush or a piece of chalk or charcoal attached to the end, to draw on paper tacked to the walls of his bedroom. As Golding has noted, ‘Confined to his bed for many of his waking as well as his sleeping hours, drawing, for obvious reasons, became increasingly paramount as a means of expression.’ Many of Matisse’s drawings of the 1950s can be seen as a sort of monochromatic complement to the colourful paper cut-outs, with the line kept to its bare essentials, without sacrificing any of its rhythmic vitality and expression.

The attribution of this drawing has been confirmed by Wanda de Guébriant and the late Marguerite Duthuit, who issued a certificate for the drawing in 1964.

Janie Bussy appears to have regarded Matisse as a somewhat pompous figure, and was envious of the time that her father spent with him. As Spurling has written, ‘Bussy’s wife and daughter…were increasingly exasperated by the amount of time Simon spent apparently dancing attendance on his prosperous old friend. Janie especially resented the contrast between Matisse’s international standing and her father’s poverty and obscurity (“She was jealous on her father’s behalf,” Lydia [Delectorskaya] said in retrospect: “Matisse was perfectly aware of the hostility felt for him by Bussy’s daughter, but he discounted it because he felt it came from wounded pride at her father’s lack of success”)…Janie, whose wit, intellect, and erudition could have made her an outstanding scholar, produced instead mild, unassertive paintings of landscapes and flowers. Both [she and her mother] amused themselves by including an ironic, mocking, mercilessly entertaining commentary on Matisse’s latest doings in their voluminous correspondence with some of the finest minds and best gossips in London and Paris.’ In 1947 Janie Bussy wrote a highly satirical memoir of Matisse, entitled ‘A Great Man’, which was read to a meeting of the ‘Memoir Club’ in Bloomsbury that year, but remained unpublished until 1986.

Perhaps not surprisingly, ‘Matisse respected Mme [Dorothy] Bussy’s cultivated mind and critical acumen, but he never felt comfortable in her company or her daughter’s. He showed up at her tea table for Simon’s sake, making solemn small talk and wearing the reddish-brown tweed suit he kept for polite occasions of this sort.’ Nevertheless, there seems to be no trace of any animosity in this affectionate portrait by Matisse of Janie Bussy, who was, like her father, a painter, and exhibited her landscapes and still life paintings at the Lefevre Gallery in London. Among stylistically comparable late portrait drawings by Matisse are a suite of ten studies of the head of his granddaughter Jacqueline, drawn in 1947 and similarly imbued with a certain intimacy; two of these drawings are in the Musée Nationale d’Art Moderne in Paris and the rest are in a private collection.

As Matisse described his approach to making portrait drawings, ‘I find myself before a person who interests me and, pencil or charcoal in hand, I set down his appearance on the paper, more or less freely. This…permits me to give free rein to my faculties of observation. At that moment, it wouldn’t do to ask a specific question, even a banal one such as ‘What time is it?’ because my reverie, my meditation upon the model, would be broken, and the result of my effort would be seriously compromised. After half-an-hour or an hour I am surprised to see a more or less precise image, which resembles the person with whom I am in contact, gradually appear on my paper. The image is revealed to me as though each stroke of charcoal erased from the glass some of the mist which until then had prevented me from seeing it.’

The present sheet displays the confident draughtsmanship of Matisse even in old age. It is among the very few independent drawings from the 1950s, a period when the artist was often bedridden with illness, and was focusing much of his energy on the seminal series of paper cut-outs that made up his final significant artistic endeavour. When he made drawings, he sometimes did so from his bed, using a long stick of bamboo with a brush or a piece of chalk or charcoal attached to the end, to draw on paper tacked to the walls of his bedroom. As Golding has noted, ‘Confined to his bed for many of his waking as well as his sleeping hours, drawing, for obvious reasons, became increasingly paramount as a means of expression.’ Many of Matisse’s drawings of the 1950s can be seen as a sort of monochromatic complement to the colourful paper cut-outs, with the line kept to its bare essentials, without sacrificing any of its rhythmic vitality and expression.

The attribution of this drawing has been confirmed by Wanda de Guébriant and the late Marguerite Duthuit, who issued a certificate for the drawing in 1964.

Henri Matisse placed drawing almost on a level with painting as a form of artistic expression, noting that ‘For me, drawing is a painting made with reduced means.’ As Isabelle Monod-Fontaine has noted, however, ‘Matisse became a great draughtsman through hard work, without the prodigious facility that Picasso had demonstrated from the age of thirteen or fourteen.' Working primarily in ink and charcoal, ‘Matisse had impressive command as a draughtsman, able to optimise the properties of several drawing mediums and, hence, their visual impact. He moved from one medium to another, modifying his working methods according to his aims.’ Matisse’s drawings are almost always complete, finished works of art, and generally served a purpose beyond that of merely preparing his paintings. As John Golding has pointed out, ‘Matisse’s drawings were seldom actual studies for paintings, and even when they are preparatory to a painting of the same subject they were almost invariably conceived and executed as drawings in their own right.’

Provenance

Given by the artist in 1952 to Jane Simone (Janie) Bussy, France

Her mother, Dorothy Bussy, née Strachey

Her posthumous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 1 July 1964, lot 47

Robert Elkon Gallery, New York

Acquired from them in the 1960s by George Weidenfeld, Baron Weidenfeld GBE, London

Thence by descent.

Her mother, Dorothy Bussy, née Strachey

Her posthumous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 1 July 1964, lot 47

Robert Elkon Gallery, New York

Acquired from them in the 1960s by George Weidenfeld, Baron Weidenfeld GBE, London

Thence by descent.

Literature

Susan Mary Alsop, ‘Sir George Weidenfeld at Home in London: The Publisher’s Artful Rooms on the Thames’, Architectural Digest, December 1991, pp.149 and 153, illustrated in situp.149;

‘Riverside Apartment for Lord Weidenfeld, Chelsea, London, 1973’, in Gillian Newberry, Geoffrey Bennison: Master Decorator, New York, 2015, p.89.

‘Riverside Apartment for Lord Weidenfeld, Chelsea, London, 1973’, in Gillian Newberry, Geoffrey Bennison: Master Decorator, New York, 2015, p.89.