Edward Coley BURNE-JONES

(Birmingham 1833 - London 1898)

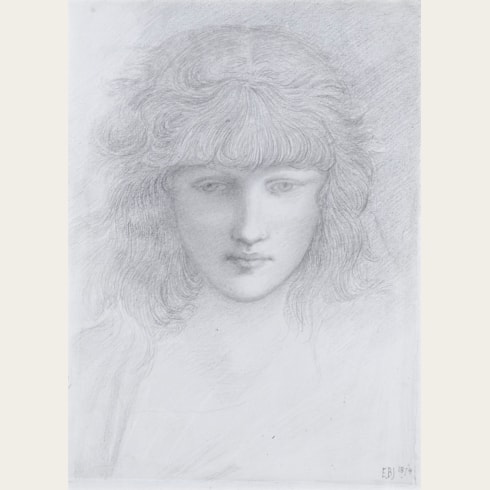

Study for the Head of a Youth (Perseus)

Signed with the artist’s initials E B-J at the lower right.

197 x 120 mm. (7 3/4 x 4 3/4 in.)

A review of the exhibition noted of The Rock of Doom that, ‘The English artist treats the Greek legend in a medieval spirit, or rather in that of the Italian Renaissance. Perseus is a slender and decidedly elegant knight, clad in mail and plate which may be dated broadly from the middle of the fifteenth century of our era…But the genius of the artist casts so powerful a spell over the visitor that he will not trouble about the incongruities of Mr. Burne Jones’s subject or his treatment of it…Literal vraisemblance does not exist for our painter, who has devised, so to say, his own nature, and represents it is his own way, and for him it is sufficient that it is self-consistent and profoundly beautiful, and romantic in the noblest sense of that much abused term. That his picture possesses these qualities, and excels in colour, tender and noble expression, exquisite illumination, and the passionate movement of the deliverer, has been admitted by all who have seen it.’

A set of full-scale cartoons for the Perseus series, painted in watercolour and gouache on canvas between 1877 and 1885, were framed and displayed in Burne-Jones’s garden studio, ‘where they were universally admired for their extraordinary vigor and dramatic power’; these are today in the collection of the Southampton City Art Gallery. The finished cartoon for The Rock of Doom at Southampton is in almost all respects identical to the final oil painting now in Stuttgart. Both depict the moment when Perseus reveals himself to the bound Andromeda by removing the helmet that had rendered him invisible.

The present sheet is characteristic of Burne-Jones’s preparatory drawings in his ‘use of a fine but soft pencil, in which he set himself high standards of finish.’ As he told his studio assistant, Thomas Rooke, in 1896, ‘I never use [pencil] to sketch with, I use it as a finishing instrument. But it’s always touch and go whether I can manage it even now. Sometimes knots will come in, and I can never get them out. I mean little black specks. There’s no drawing I consider perfect. I often let one pass only because of expression, or facts I want in it, but unless – if I’ve once india-rubbered it, it doesn’t make a good drawing. I look on a perfectly successful drawing as one built up on a groundwork of clear lines till it’s finished.’

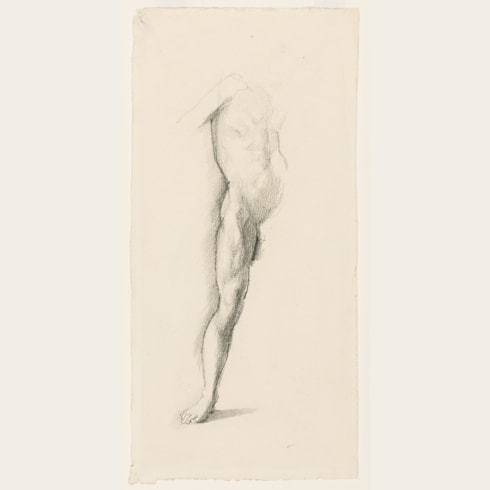

When he received the commission for the Perseus series from Balfour, Burne-Jones immediately began making drawings and studies for the scheme. As one of his modern biographers has noted, ‘As with all his new subjects there was an immediate onrush of activity…His sketchbooks show the depth of his concentration as the subject started gripping his imagination. There are pages and pages of preliminary studies…There is still the same love and exuberance of drawing for its own sake people noticed in Burne-Jones when he was a boy.’

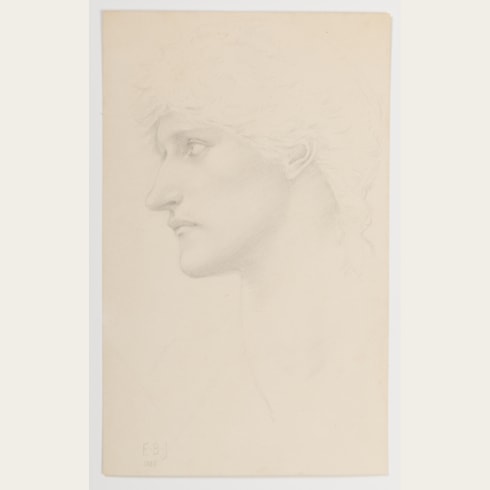

A large number of pencil studies for the Perseus series are today in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, while others are in the collections of the British Museum, Tate Britain, the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Courtauld Gallery in London, the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery in Birmingham, the Manchester Art Gallery and the Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, and the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight, as well as the Art Gallery of South Australia in Adelaide, the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen, and elsewhere.

Another pencil study for the head of Perseus in The Rock of Doom was sold at auction in London in 2010, while what appears to be another study for the same head was sold at auction in 2000.

The leading member of the second generation of Pre-Raphaelite painters, Edward Burne-Jones studied at Exeter College, Oxford, where he met William Morris. The two were to remain lifelong friends and colleagues, with Burne-Jones executing designs for stained glass windows, ceramic tiles and tapestries for Morris and Company for more than thirty-five years. Another close friend was Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who gave Burne-Jones some of the little artistic training he received, otherwise being largely self-taught. From early in his career Burne-Jones enjoyed a measure of success, particularly as a designer of stained glass panels. In 1859 he made the first of four trips to Italy, a country whose art he found of considerable inspiration throughout his life. In 1877 he showed a total of eight paintings at the inaugural exhibition at the Grosvenor Gallery, established as a more radical alternative to the Royal Academy. The success of these pictures, and his continued participation in the yearly Grosvenor exhibitions, established Burne-Jones's reputation as a leader of the Aesthetic movement. His fame also spread to Europe, and in particular Paris, where his painting of King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid was greatly admired at the Exposition Universelle of 1889.

A passionate and prolific draughtsman, Burne-Jones produced countless preparatory studies and cartoons for his paintings, as well as drawings intended as independent works of art in their own right, in black and red chalk, pencil, pen and watercolour. His drawings were, indeed, of arguably greater significance to him than his finished paintings; as John Christian has noted, Burne-Jones ‘was always a draughtsman first and a painter second.’ Similarly, the artist’s friend Graham Robertson wrote that ‘He was pre-eminently a draughtsman, and one of the greatest in the whole history of Art…as a master of line he was always unequalled; to draw was his natural mode of expression – line flowed from him almost without volition.’ Although he occasionally gave drawings away as presents, and also sometimes exhibited them in public, Burne-Jones seems to have kept most of his drawings in his studio until his death, after which they were dispersed.

Provenance

Exhibition