Peter Paul RUBENS

(Siegen 1577 - Antwerp 1640)

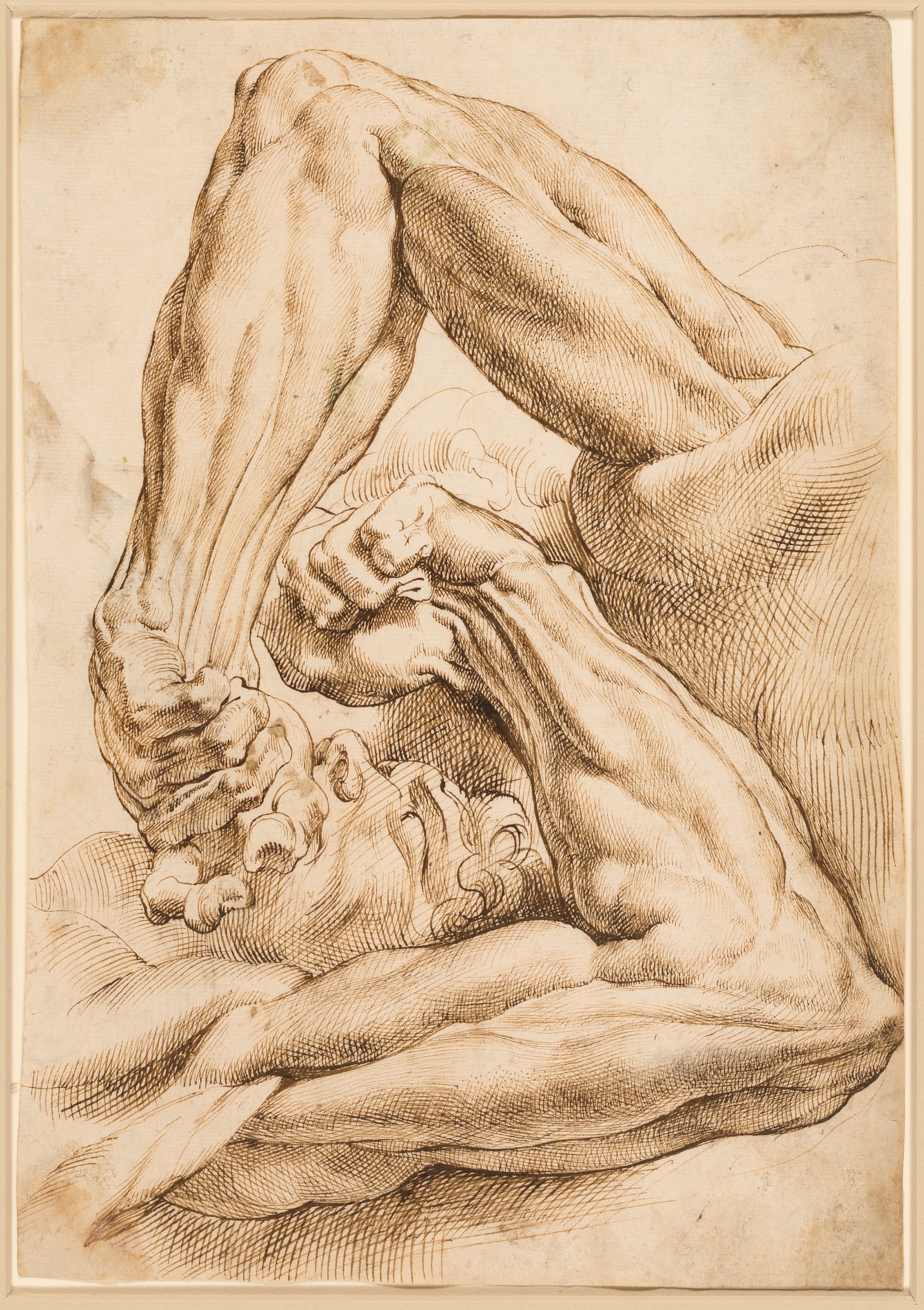

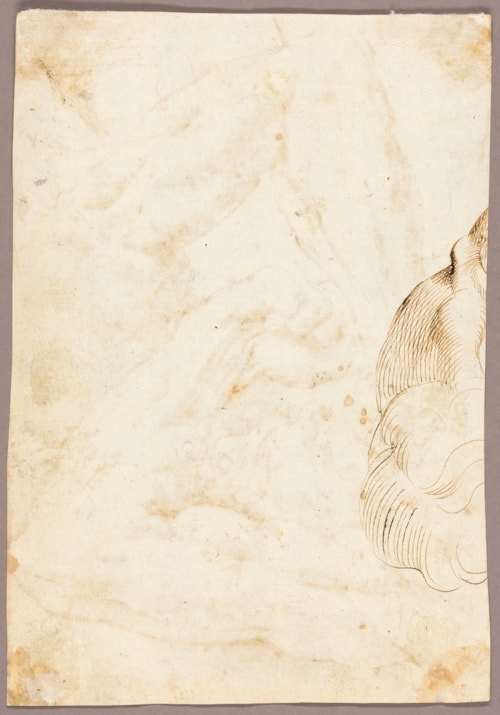

A Sheet of Anatomical Studies: A Left Forearm in Two Related Positions with Parts of the Torsi and a Head [recto]; Fragment of a Drawing of the Hair and Shoulder of a Man [verso]

Sold

Pen and brown ink. 269 x 187 mm. (10 5/8 x 7 3/8 in.)

ACQUIRED BY THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO.

ACQUIRED BY THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO.

This remarkable drawing is one of a group of around fourteen anatomical studies by Rubens, eleven of which, including the present sheet, were acquired by Sir Roger Newdigate (1719-1806) in the middle of the 18th century and remained in the Newdigate (or Newdegate) collection until they were dispersed at auction in London in 1987. (A handful of other anatomical studies by Rubens, not part of the Newdigate group, are in the Albertina in Vienna and the Devonshire Collection at Chatsworth, as well as formerly in the Martin Bodmer Foundation in Geneva.)

Rubens is thought to have made these ecorché drawings to illustrate a never-published Anatomy Book, and probably also as models for prints. Indeed, a number of the drawings were engraved, in reverse, by Paulus Pontius, one of the leading engravers associated with Rubens and his workshop; these were published in Antwerp after the master’s death in 1640. In the late 1620s Rubens’s assistant Willem Panneels made several drawn copies after this small group of anatomy drawings, some of which he inscribed as being taken from the painter’s ‘annotomibock’; these are part of the so-called Rubens cantoor group of around five hundred drawings – all copies after originals by Rubens, many drawn by Panneels – which are today in the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen.

The ‘annotomibock’ or ‘anatomy book’ mentioned by Panneels was dismembered after Rubens’s death, and the drawings it contained, including the present sheet, were dispersed. As Anne-Marie Logan has noted, ‘The anatomy book shows Rubens learning the motion of the human body, how muscles function under tension and how they are attached to the skeleton’, while Jeffrey Muller adds, ‘Rubens had to get beneath the skin to see how the muscles of the hand would grasp a sword or how the muscles of the face might grimace in pain or smile in love...[the anatomy drawings] document the programmatic efforts Rubens made in Italy, from 1600 to 1608, to master the proportions, ideal forms, movements, and gestures of man’s body. As part of this program, anatomy was fundamental.’

Rubens’s anatomical drawings have generally been dated to his time in Italy, between 1600 and 1608, and more particularly towards the earlier part of this period. The late 17th century French amateur and writer Roger de Piles, one of the artist’s earliest biographers, noted that Rubens greatly admired the anatomical studies of Leonardo da Vinci, which he is likely to have seen in Spain when he was sent on a diplomatic mission to Madrid by the Duke of Mantua. He may also have attended human dissections during his time in Italy, perhaps at the famous anatomical theatre in Padua, which was not far from Mantua, where he was court painter. However, these ecorché drawings by Rubens appear not to have been drawn from actual dissected bodies. At least some of the full-length ecorché studies appear to have been copied from a bronze sculpture of a flayed man by the Dutch sculptor Willem van Tetrode (c.1525-1580), which Rubens studied from different angles.

A superb example of Rubens’s virtuoso penmanship, the present sheet reflects the artist’s profound and concentrated interest in anatomical study. In this drawing, Rubens represented the flayed arms of two male figures, shown in an interlocking arrangement. (It is interesting to note that Willem Panneels’s copy after the present sheet in Copenhagen separates the two studies of a flayed left arm and places them more or less side by side on the page, a much less dramatic composition than is seen here, in Rubens’s original drawing.)

That this drawing was once half of a larger sheet of anatomical studies - and as such was almost certainly part of a notebook - is shown in the fact that the pen and ink sketch on the verso of the present sheet is a continuation of another anatomical drawing by Rubens of A Left Forearm in Two Positions and a Right Forearm, also once part of the Newdigate group and today in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Several other drawings from this group of anatomical drawings by Rubens show studies of what appears to be the same model of a flayed left arm, examined from several different points of view; one of these is a double-sided sheet today in the Art Gallery of Ontario, and others are in private collections.

As David Jaffé has written, ‘Examining Rubens’s ecorché studies transforms the way we read his painted figures: these ‘anatomical drawings’ were vital to the development of his Michelangelesque style of about 1610. The formidable agility and rippling musculature that gives his figures their almost superhuman qualities take their authority from these studies...The intertwined arms of the ecorché studies expose the bones of Rubens’s spatial thinking.’

Rubens is thought to have made these ecorché drawings to illustrate a never-published Anatomy Book, and probably also as models for prints. Indeed, a number of the drawings were engraved, in reverse, by Paulus Pontius, one of the leading engravers associated with Rubens and his workshop; these were published in Antwerp after the master’s death in 1640. In the late 1620s Rubens’s assistant Willem Panneels made several drawn copies after this small group of anatomy drawings, some of which he inscribed as being taken from the painter’s ‘annotomibock’; these are part of the so-called Rubens cantoor group of around five hundred drawings – all copies after originals by Rubens, many drawn by Panneels – which are today in the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen.

The ‘annotomibock’ or ‘anatomy book’ mentioned by Panneels was dismembered after Rubens’s death, and the drawings it contained, including the present sheet, were dispersed. As Anne-Marie Logan has noted, ‘The anatomy book shows Rubens learning the motion of the human body, how muscles function under tension and how they are attached to the skeleton’, while Jeffrey Muller adds, ‘Rubens had to get beneath the skin to see how the muscles of the hand would grasp a sword or how the muscles of the face might grimace in pain or smile in love...[the anatomy drawings] document the programmatic efforts Rubens made in Italy, from 1600 to 1608, to master the proportions, ideal forms, movements, and gestures of man’s body. As part of this program, anatomy was fundamental.’

Rubens’s anatomical drawings have generally been dated to his time in Italy, between 1600 and 1608, and more particularly towards the earlier part of this period. The late 17th century French amateur and writer Roger de Piles, one of the artist’s earliest biographers, noted that Rubens greatly admired the anatomical studies of Leonardo da Vinci, which he is likely to have seen in Spain when he was sent on a diplomatic mission to Madrid by the Duke of Mantua. He may also have attended human dissections during his time in Italy, perhaps at the famous anatomical theatre in Padua, which was not far from Mantua, where he was court painter. However, these ecorché drawings by Rubens appear not to have been drawn from actual dissected bodies. At least some of the full-length ecorché studies appear to have been copied from a bronze sculpture of a flayed man by the Dutch sculptor Willem van Tetrode (c.1525-1580), which Rubens studied from different angles.

A superb example of Rubens’s virtuoso penmanship, the present sheet reflects the artist’s profound and concentrated interest in anatomical study. In this drawing, Rubens represented the flayed arms of two male figures, shown in an interlocking arrangement. (It is interesting to note that Willem Panneels’s copy after the present sheet in Copenhagen separates the two studies of a flayed left arm and places them more or less side by side on the page, a much less dramatic composition than is seen here, in Rubens’s original drawing.)

That this drawing was once half of a larger sheet of anatomical studies - and as such was almost certainly part of a notebook - is shown in the fact that the pen and ink sketch on the verso of the present sheet is a continuation of another anatomical drawing by Rubens of A Left Forearm in Two Positions and a Right Forearm, also once part of the Newdigate group and today in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Several other drawings from this group of anatomical drawings by Rubens show studies of what appears to be the same model of a flayed left arm, examined from several different points of view; one of these is a double-sided sheet today in the Art Gallery of Ontario, and others are in private collections.

As David Jaffé has written, ‘Examining Rubens’s ecorché studies transforms the way we read his painted figures: these ‘anatomical drawings’ were vital to the development of his Michelangelesque style of about 1610. The formidable agility and rippling musculature that gives his figures their almost superhuman qualities take their authority from these studies...The intertwined arms of the ecorché studies expose the bones of Rubens’s spatial thinking.’

Provenance

Probably acquired on his Grand Tour between 1738 and 1740 by Sir Roger Newdigate, 5th Bt., Arbury, Warwickshire

The Newdegate Settlement, London

Their sale, London, Christie’s, 6 July 1987, lot 65

Bernard Quaritch Ltd., London

Hazlitt Gooden & Fox, London, in 1992

Mr. and Mrs. Christopher Rupp, New York

Their anonymous sale, New York, Sotheby’s, 23 January 2001, lot 156

W. M. Brady and Co., New York, and Thomas Williams Fine Art Ltd., London

Private collection, Massachusetts.

The Newdegate Settlement, London

Their sale, London, Christie’s, 6 July 1987, lot 65

Bernard Quaritch Ltd., London

Hazlitt Gooden & Fox, London, in 1992

Mr. and Mrs. Christopher Rupp, New York

Their anonymous sale, New York, Sotheby’s, 23 January 2001, lot 156

W. M. Brady and Co., New York, and Thomas Williams Fine Art Ltd., London

Private collection, Massachusetts.

Literature

Michael Jaffé, ‘Rubens’s Anatomy Book’, in London, Christie’s, Old Master Drawings, 6-7 July 1987, pp.58-59; Jeffrey M. Muller, ‘Rubens’ Anatomieboek / Rubens’ Anatomy Book’, in Antwerp, Rubenshuis, Rubens Cantoor: een verzameling tekeningen ontstaan in Rubens’ atelier, exhibition catalogue, 1993, p.97, no.7, illustrated in colour p.57, pl.3; New York, W. M. Brady and Co., and London, Thomas Williams Fine Art Ltd., Old Master Drawings, 2001, unpaginated, no.16; Anne-Marie Logan and Michiel C. Plomp, Peter Paul Rubens: The Drawings, exhibition catalogue, New York, 2005, pp.98-100, fig.53, under no.16; Anne-Marie Logan, ‘Rubens’s drawings after Julius Held’, Oud Holland, 2007, Nos.3-4, p.165; Clifford S. Ackley, ‘Master drawings from the collection of Horace Wood Brock’, The Magazine Antiques, February 2009, p.56, illustrated p.52, fig.1; Horace Wood Brock, ‘The Truth about Beauty’, in Horace Wood Brock, Martin P. Levy and Clifford S. Ackley, Splendor and Elegance: European Decorative Arts and Drawings from the Horace Wood Brock Collection, exhibition catalogue, Boston, 2009, p.13, illustrated p.12; Clifford S. Ackley, ‘The Intuitive Eye: Drawings and Paintings from the Collection of Horace Wood Brock’, in Brock, Levy and Ackley, ibid., pp.90-92; New York, W. M. Brady and Co., Master Drawings 1530-1920, 2012, exhibition catalogue, unpaginated, under no.7 (entry by Anne-Marie Logan); Domenico Laurenza, ‘Art and Anatomy in Renaissance Italy: Images from a Scientific Revolution’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Winter 2012, p.43, fig.60; Victoria Sancho Lobis, Rubens, Rembrandt and Drawing in the Golden Age, exhibition catalogue, Chicago, 2019-2020, p.312, no.11, illustrated p.57; Hans Jakob Meier, ‘Anatomical Studies (Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard, 20.1)’ [book review], The Burlington Magazine, August 2023, p.921, fig.4.

Exhibition

Antwerp, Rubenshuis, Rubens Cantoor: een verzameling tekeningen ontstaan in Rubens’ atelier, 1993, no.7; New York, W. M. Brady and Co., Old Master Drawings, 2001, no.16; Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Splendor and Elegance: European Decorative Arts and Drawings from the Horace Wood Brock Collection, 2009, no.1; Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago, Rubens, Rembrandt and Drawing in the Golden Age, 2019-2020, no.11.