Pierre BONNARD

(Fontenay-aux-Roses 1867 - Le Cannet 1947)

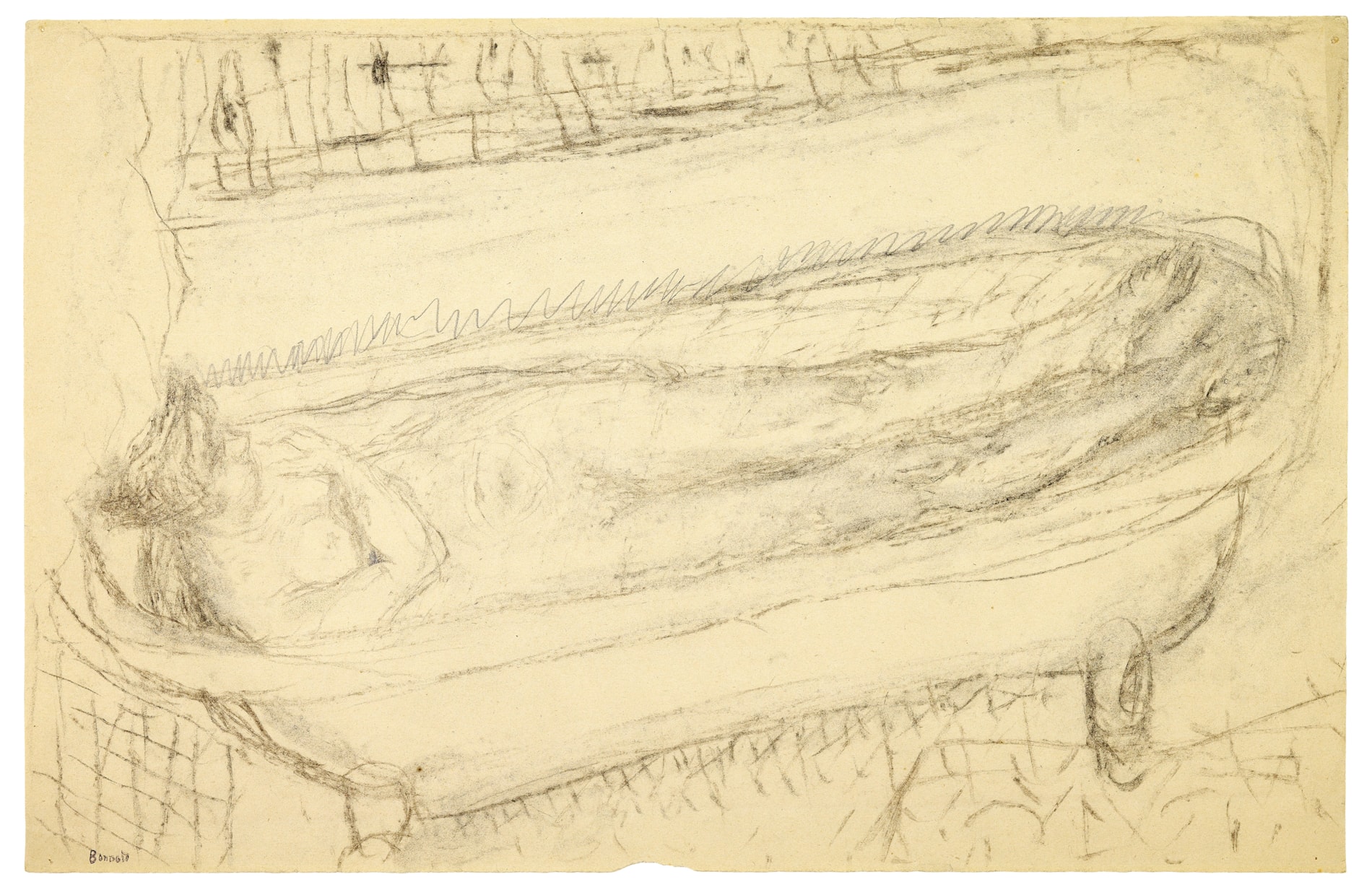

Bather

Sold

Brown and black chalk and pencil on buff paper.

Stamped with the large version of the Bonnard estate stamp (Lugt 3886) at the lower left.

321 x 503 mm. (12 5/8 x 19 3/4 in.)

Stamped with the large version of the Bonnard estate stamp (Lugt 3886) at the lower left.

321 x 503 mm. (12 5/8 x 19 3/4 in.)

Although the nude female figure occurs frequently in Pierre Bonnard’s sketchbooks, as well as in paintings and photographs, this interest only began around 1900, a few years after he had met his muse and future wife Marthe. She was to be his companion and model for nearly thirty years before she and Bonnard were married in 1925. Marthe would become the dominant female presence in his late work, and Bonnard continued to portray her as a young woman, with a slight, delicate body, even well into her later years.

Like Edgar Degas, Bonnard often depicted women at intimate moments of their daily toilette. Around 1924 he began painting several canvases devoted to the subject of a nude bather in a bathtub or bathroom, a theme also found in several lithographs of the same period. The model for many of these paintings was Marthe, and the theme occupied the artist throughout the 1930s and for much of the later period of his long career. As one scholar has written of these works, ‘Bonnard’s nudes at their toilette reflect the evolution of a highly personal vision, replete with references to the artist’s own art, his external experiences, and the long and complex artistic tradition in which they are located. The model is most often Marthe – Marthe at her bath, Marthe caught unaware before her dressing table, Marthe partially glimpsed through a mirror. Yet, while the paintings refer to a specific woman, they are about Bonnard’s way of seeing.’ And, as his fellow Nabis artist Maurice Denis further noted, ‘These intimate scenes by Bonnard, these young women dreaming, doing their hair, undressing, these women sewing, or reading, these bathers with their lissom bodies and pink thighs, all are imbued with tenderness, with optimism, and, in a word, poetry.’

The present sheet may be related to Bonnard’s large painting Nude in the Bath (Nu dans le bain), painted in 1936, in the collection of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. This was one of a series of superb late paintings treating the subject of a nude woman lying full-length in a bathtub; a theme that came to preoccupy the artist throughout the last two decades of his career. Although the composition of the drawing is in reverse to that of the painting, the present sheet is likely to be a first idea for the canvas. As Sasha Newman has written, with particular reference to the Petit Palais painting, ‘Bonnard’s later women in the bath evolved into something wholly original and are among the greatest nudes painted in the twentieth century. Bonnard’s nudes at their toilette always remain apart – yet, their separateness is most powerfully expressed in the bathtub series. The woman is enclosed, as if in a shell or a womb. She floats in the water which surrounds her, in the manner of a Monet waterlily or a drowning Ophelia...Neither dead nor alive, she exists in her self-enclosed realm, collecting all of the light and color refractions that bounce off the tiles and water and play on her flesh...The pose of the model relates directly to notations in Bonnard’s diaries – head against the back of the tub, arms and legs fully extended, suspended in her white porcelain-like shell.’ A later variant of the Petit Palais canvas, painted between 1937 and 1939, is in a private collection.

Bonnard’s obsessive treatment of the particular theme of a female nude floating in a bathtub - first seen in the painting The Bath of 1925, today in the collection of Tate Modern in London - was repeated in several paintings of the late 1930s and early 1940s, culminating in a Nude in a Bathtub and a Small Dog, begun in 1941 and completed five years later, in the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh. The subject of Marthe immersed in a bath is also found in over twenty drawings in Bonnard’s sketchbooks and diaries from the 1920s onwards; one of these, a pencil drawing from one of the artist’s small sketchbooks, is particularly close to the composition of the present sheet, and must have preceded it.

As the scholar Marina Ferretti Bocquillon has stated, ‘The great recumbent nudes are to Bonnard’s art what the Nymphéas are to Claude Monet’s oeuvre, the triumph of a light that transfigures reality. The model’s body melts into a play of tints, and the clarity of the Midi dissolves even the oval of the bathtub...It is not Marthe’s body that disintegrates into the bathwater, but all of reality that vanishes into the orchestrated iridescence.’ Nevertheless, as the artist commented while working on a painting from this groundbreaking bathtub series, ‘I would never again dare engage upon such a difficult theme. I can’t make it come out as I wish. I have been at it for six months and I still have several months’ work to do.’

Like Edgar Degas, Bonnard often depicted women at intimate moments of their daily toilette. Around 1924 he began painting several canvases devoted to the subject of a nude bather in a bathtub or bathroom, a theme also found in several lithographs of the same period. The model for many of these paintings was Marthe, and the theme occupied the artist throughout the 1930s and for much of the later period of his long career. As one scholar has written of these works, ‘Bonnard’s nudes at their toilette reflect the evolution of a highly personal vision, replete with references to the artist’s own art, his external experiences, and the long and complex artistic tradition in which they are located. The model is most often Marthe – Marthe at her bath, Marthe caught unaware before her dressing table, Marthe partially glimpsed through a mirror. Yet, while the paintings refer to a specific woman, they are about Bonnard’s way of seeing.’ And, as his fellow Nabis artist Maurice Denis further noted, ‘These intimate scenes by Bonnard, these young women dreaming, doing their hair, undressing, these women sewing, or reading, these bathers with their lissom bodies and pink thighs, all are imbued with tenderness, with optimism, and, in a word, poetry.’

The present sheet may be related to Bonnard’s large painting Nude in the Bath (Nu dans le bain), painted in 1936, in the collection of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. This was one of a series of superb late paintings treating the subject of a nude woman lying full-length in a bathtub; a theme that came to preoccupy the artist throughout the last two decades of his career. Although the composition of the drawing is in reverse to that of the painting, the present sheet is likely to be a first idea for the canvas. As Sasha Newman has written, with particular reference to the Petit Palais painting, ‘Bonnard’s later women in the bath evolved into something wholly original and are among the greatest nudes painted in the twentieth century. Bonnard’s nudes at their toilette always remain apart – yet, their separateness is most powerfully expressed in the bathtub series. The woman is enclosed, as if in a shell or a womb. She floats in the water which surrounds her, in the manner of a Monet waterlily or a drowning Ophelia...Neither dead nor alive, she exists in her self-enclosed realm, collecting all of the light and color refractions that bounce off the tiles and water and play on her flesh...The pose of the model relates directly to notations in Bonnard’s diaries – head against the back of the tub, arms and legs fully extended, suspended in her white porcelain-like shell.’ A later variant of the Petit Palais canvas, painted between 1937 and 1939, is in a private collection.

Bonnard’s obsessive treatment of the particular theme of a female nude floating in a bathtub - first seen in the painting The Bath of 1925, today in the collection of Tate Modern in London - was repeated in several paintings of the late 1930s and early 1940s, culminating in a Nude in a Bathtub and a Small Dog, begun in 1941 and completed five years later, in the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh. The subject of Marthe immersed in a bath is also found in over twenty drawings in Bonnard’s sketchbooks and diaries from the 1920s onwards; one of these, a pencil drawing from one of the artist’s small sketchbooks, is particularly close to the composition of the present sheet, and must have preceded it.

As the scholar Marina Ferretti Bocquillon has stated, ‘The great recumbent nudes are to Bonnard’s art what the Nymphéas are to Claude Monet’s oeuvre, the triumph of a light that transfigures reality. The model’s body melts into a play of tints, and the clarity of the Midi dissolves even the oval of the bathtub...It is not Marthe’s body that disintegrates into the bathwater, but all of reality that vanishes into the orchestrated iridescence.’ Nevertheless, as the artist commented while working on a painting from this groundbreaking bathtub series, ‘I would never again dare engage upon such a difficult theme. I can’t make it come out as I wish. I have been at it for six months and I still have several months’ work to do.’

A compulsive draughtsman, Pierre Bonnard relied on his studies and sketches extensively in the preparation of his pictures. Most of his drawings seem to have been made in the process of developing the composition of a painting, and indeed he seems to have preferred to work from drawings rather than relying on direct observation. He made use of whatever paper came to hand, sometimes lined or squared pages of cheap paper or small sketchbooks, and generally of a small enough size to fit into his pocket. He almost always used a hard or soft pencil and only very rarely applied colour to his drawings, relying on the strength and shading of the pencil strokes to suggest tone and colour. In conversation with his nephew Charles Terrasse, Bonnard noted that ‘I am drawing incessantly - after drawing comes the composition which must have a perfect equilibrium, a well constructed picture is the battle half won, the art of composition is so powerful that with only black and white - a pencil, a pen or a lithographic pencil, one arrives at results as complete and of a quality nearly as beautiful as with a whole arsenal of colours.’

Bonnard rarely parted with his drawings, which were never intended to be exhibited or, indeed, regarded as independent works of art. Nevertheless, the artist’s work as a draughtsman is crucial to an understanding of his approach to painting. As Jack Flam has written, ‘Bonnard’s drawings are often very small, and as a result they are frequently overlooked in discussions of modern drawing. But their formal variety and sensitivity of touch are remarkable, as is the often fluctuant nature of their imagery. Although many of Bonnard’s drawings seem like shorthand notations of visual information recorded for later use in paintings, they are nonetheless effective as independent entities precisely because of the intensity of perception they incorporate. They also demonstrate an extraordinary sensitivity to the nature of the medium itself, unadorned by elaborate technical procedures.’

Provenance

The estate of the artist (Lugt 3886)

Daniel Wildenstein, Paris and New York

Private collection, Pennsylvania.

Literature

Michel Terrasse, Bonnard: du dessin au tableau, Paris, 1996, illustrated p.254; Sarah Whitfield, Bonnard, exhibition catalogue, London and New York, 1998, p.202, fig.114, under no.75; Emily Braun et al., New York Collects: Drawings and Watercolors 1900-1950, exhibition catalogue, New York, 1999, p.38, note 3, under no.3 (entry by Jack Flam).