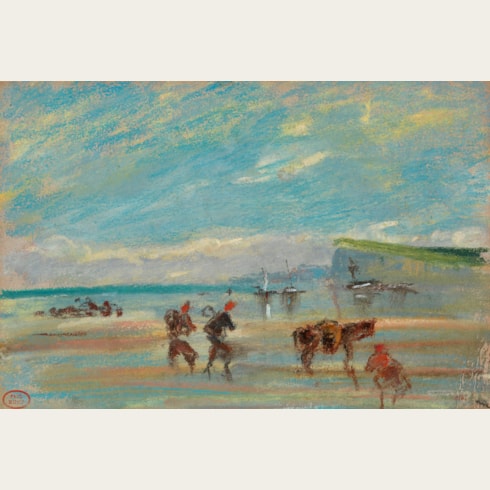

Paul HUET

(Paris 1803 - Paris 1869)

The ‘Song of the Sea’ Cliffs at Nanjizal Cove, Land’s End, Cornwall

Sold

Watercolour, over an underdrawing in pencil.

Inscribed Grotte du chant de la mer Land’s end. at the lower right.

260 x 362 mm. (10 1/4 x 14 1/4 in.)

Inscribed Grotte du chant de la mer Land’s end. at the lower right.

260 x 362 mm. (10 1/4 x 14 1/4 in.)

The present sheet may be dated to the summer of 1862, when Paul Huet made his first and only visit to England. As might be expected given his abiding interest in the English school of landscape painting and drawing, Huet made a number of sketches on his travels which, apart from London and Windsor, included visits to Tunbridge Wells, Salisbury and Stonehenge. He also visited Devon and Cornwall in southwestern England, a region he particularly admired, and which reminded him of his beloved Normandy. As Huet wrote to his wife in a letter of July 1862, ‘Nous sommes dans le véritable Cornwall, pays vraiment pittoresque, l’ancienne Bretagne qui est à l’Angleterre ce que la Bretagne française est à la Normandie…Des détails charmants, une fraîcheur inouïe, expression générale de toute l’Angleterre et beaucoup de rapports avec la Normandie et l’entrée de la Bretagne, voilà ce que vous trouverez.’

During his visit to this area Huet was based in the Cornish town of Liskeard, from which he undertook a number of sketching trips. His travels took him as far west as Land’s End, where he made several watercolour views of some of the distinctive sights of the surrounding area, such as the balancing Logan Rock at Treen and this view of a tall, narrow rock arch known as the ‘Song of the Sea’ (‘Zawn Pyg’), part of a sea cliff on an isolated beach at Nanjizal Cove, two kilometres from Land’s End. The artist must have visited the beach - which remains inaccessible by road today - by walking along the coastal path from Land’s End in the north.

A closely related watercolour by Huet of the same view, seen from slightly further down the beach, was exhibited in London in 1969.

During his visit to this area Huet was based in the Cornish town of Liskeard, from which he undertook a number of sketching trips. His travels took him as far west as Land’s End, where he made several watercolour views of some of the distinctive sights of the surrounding area, such as the balancing Logan Rock at Treen and this view of a tall, narrow rock arch known as the ‘Song of the Sea’ (‘Zawn Pyg’), part of a sea cliff on an isolated beach at Nanjizal Cove, two kilometres from Land’s End. The artist must have visited the beach - which remains inaccessible by road today - by walking along the coastal path from Land’s End in the north.

A closely related watercolour by Huet of the same view, seen from slightly further down the beach, was exhibited in London in 1969.

As a young boy and only child, Paul Huet spent his summers drawing and sketching on the Ile Séguin, near Paris, and after leaving school decided to take up studies as an artist. In 1820, while training in the studio of Baron Gros at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, he met and befriended a fellow student, the young Englishman Richard Parkes Bonington. Huet, who like all of Gros’s students was engaged in the practice of plein-air sketching, learned the English manner of watercolour technique from Bonington, and his rapid command of the medium has meant that works by the two artists have often been confused. At around the same time, he also came into contact with another young painter, Eugène Delacroix, who shared a studio in Paris with Bonington. Delacroix had admired Huet’s watercolours in a shop window, and who was to remain a lifelong friend. Another early influence were the landscape paintings of John Constable, which were a revelation to the young artist when they were first exhibited in France at the Salon of 1824. In 1826, Huet assisted Delacroix by painting the landscape background of the latter’s full-length portrait of Louis-Auguste Schwiter, now in the National Gallery in London.

Following his own Salon debut in 1827, Huet accompanied Bonington on a sketching tour of the Normandy coast. This was to be the first of his extensive travels throughout France, and the artist was to return often to the regions of Normandy, the Auvergne and Provence, as well as forests of Compiègne and Fontainebleau, closer to Paris. At the Salon of 1831 Huet’s work was praised by the critic Gustave Planche, who noted that ‘M. Paul Huet is today placed at the head of the new school of landscapists...[he] has wanted, and still wants, after numerous and purely personal reflections, to take landscape painting back to nature, and that to get there he has sensed the imperious necessity of breaking violently and brusquely with currently adopted principles.’

Since both he and his wife were often beset by poor health, Huet made several visits to the South of France between 1833 and 1845, and also travelled to Italy in 1841. Wherever he went, he made numerous drawings and sketches sur le motif in pencil, pastel and watercolour, all imbued with a remarkable feeling for light and colour. As he once wrote, ‘pour le paysage la couleur est indispensable: c’est sa plus vive expression, il ne peut s’en passer, pas plus que du dessin.’ In 1837 Huet was appointed drawing master to the Duchesse d’Orléans, and the following year received an important commission from the Duc d’Orléans for a series of finished watercolour views of the major cities of France, for which he was paid two thousand francs. Much of Huet’s work remained with his family after his death in 1869, with only a part of this studio inventory dispersed at auction in Paris in 1878.

As the modern scholar Alain de Leiris has noted, ‘Less well known than his friends Delacroix and Bonington, Paul Huet was nevertheless a major force in French landscape. He had a long career and the support of the critics of his generation. Like Corot, he pursued his dream, never abandoning his early worship of nature, essentially unaffected by changing tastes and contemporary movements; yet these same movements, the Barbizon painters, the Impressionists, are indebted to him as a leader in the naturalistic landscape development, even though few among the members of these schools acknowledged this debt…[Huet’s watercolours] represent, unlike his paintings, lithographs, and etchings, the more private aspects of his oeuvre. Like drawings, these studies have the freshness of first thoughts and records of first impressions. But, however spontaneous and rapid these records may be – and there are relatively elaborate landscapes among them – they have the imprint of Huet’s style...The technique is not as fluid as Bonington’s, not as facile as Isabey’s, not as instinctive as Delacroix’s. Its particular virtue is the exploitation of the full range of colors and transparencies of watercolor and, resulting from this wealth, a sense of earth – its breadth, its topographical accidents, its fertility, its varied vegetation…The watercolors of Huet best illustrate the particular virtues of the French manner in watercolor, especially its functional, modest role as the vehicle of a muted, sometimes gentle and sometimes intense, dialogue with nature. The testimony of many of his contemporaries bears this out. They all agreed that Paul Huet was a poet.’

Provenance

In the artist’s studio at the time of his death, with the atelier stamp (Lugt 1268) at the lower right

By descent in the family of the artist, until 2014.

By descent in the family of the artist, until 2014.