Samuel PALMER

(Newington 1805 - Redhill 1881)

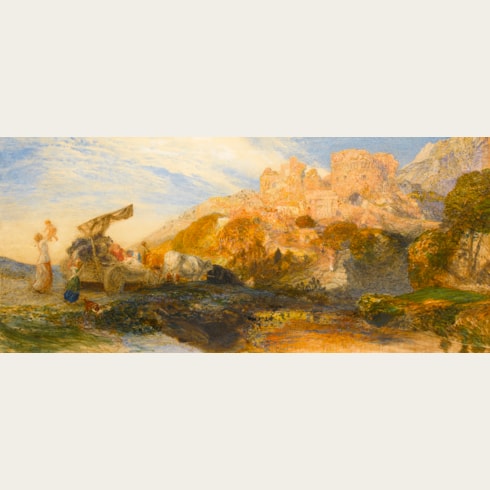

In the Chequered Shade

Sold

Watercolour, heightened with gouache and gum arabic, over an underdrawing in pencil.

Indistinctly signed and dated S. PALMER / 1861 at the lower right.

202 x 432 mm. (8 x 17 in.)

Indistinctly signed and dated S. PALMER / 1861 at the lower right.

202 x 432 mm. (8 x 17 in.)

The title of this watercolour is taken from the 17th century English poet John Milton’s pastoral ode L’Allegro, published in 16451. Milton’s work was a constant influence on Samuel Palmer throughout his life, and his work is filled with references to images found in Milton’s poetry. In 1863 Palmer began work on a series of large watercolours illustrating lines from Milton’s poetry, commissioned from him by the solicitor Leonard Rowe Valpy; a project that was to occupy the artist for the rest of his life. In the present watercolour, Palmer depicts a woman carrying an urn of water on her head to the right, while a hunting party chases a stag with attendant dogs ‘in the chequered shade’ to the left. The high viewpoint, looking down on an Italianate landscape, and the interest in effects of light and shade are typical features of Palmer’s work of the period.

Both In the Chequered Shade and In Vintage Time were among seven works sent by Palmer to the annual exhibition of the Royal Society of Painters in Water-Colours in 1861. As a recent Palmer biographer has noted, however, ‘At the Old Watercolour Society exhibition his works had been dismally hung. The committee excused itself by saying that his pictures were so powerful that nothing could stand against them; but the outcome was that only three of the seven works submitted had been sold. The painter was in low spirits.’

Nevertheless, one review of the 1861 OWCS exhibition – in which the present pair was shown - noted that ‘one of the most original and remarkable landscapists in the room is Mr. Samuel Palmer, who, besides throwing an air of poetry over the scenes he represents, peoples them with figures perfectly well drawn, and with a classic style about them which reminds one of an earlier and more learned school of landscape-art. Like the generality of the artists of our day, he is too much devoted to one peculiar aspect of atmosphere – glowing sunsets, which, however, he manages so as to produce a considerable amount of variety. “After the Storm” (183), “In Vintage Time” (216) and “Sunset in the Mountains” (226) are all examples eminently deserving the high character we have specified.’

Another anonymous review of the exhibition made note of the present sheet in particular: ‘Mr. Samuel Palmer contributes his usual number of drawings, which still present his well-known merits; but we are happy to say on a more modified style of art. The work entitled “Distant Mountains” is not quite so good as some of the others. “The Chequered Shade” is a much more pleasing and successful production, in which the light is brilliant, broad and well distributed, fading in its vividness, and increasing in its fitfulness on the figures in the foreground.’

In this watercolour, Palmer depicts a woman carrying an urn of water on her head to the right with a hunting party chasing a stag with attendant dogs ‘in the chequered shade’ to the left. The high viewpoint, looking down on an Italianate landscape, and the combination of light and shade is a typical feature of Palmer’s work of the period.

Both In the Chequered Shade and In Vintage Time were among seven works sent by Palmer to the annual exhibition of the Royal Society of Painters in Water-Colours in 1861. As a recent Palmer biographer has noted, however, ‘At the Old Watercolour Society exhibition his works had been dismally hung. The committee excused itself by saying that his pictures were so powerful that nothing could stand against them; but the outcome was that only three of the seven works submitted had been sold. The painter was in low spirits.’

Nevertheless, one review of the 1861 OWCS exhibition – in which the present pair was shown - noted that ‘one of the most original and remarkable landscapists in the room is Mr. Samuel Palmer, who, besides throwing an air of poetry over the scenes he represents, peoples them with figures perfectly well drawn, and with a classic style about them which reminds one of an earlier and more learned school of landscape-art. Like the generality of the artists of our day, he is too much devoted to one peculiar aspect of atmosphere – glowing sunsets, which, however, he manages so as to produce a considerable amount of variety. “After the Storm” (183), “In Vintage Time” (216) and “Sunset in the Mountains” (226) are all examples eminently deserving the high character we have specified.’

Another anonymous review of the exhibition made note of the present sheet in particular: ‘Mr. Samuel Palmer contributes his usual number of drawings, which still present his well-known merits; but we are happy to say on a more modified style of art. The work entitled “Distant Mountains” is not quite so good as some of the others. “The Chequered Shade” is a much more pleasing and successful production, in which the light is brilliant, broad and well distributed, fading in its vividness, and increasing in its fitfulness on the figures in the foreground.’

In this watercolour, Palmer depicts a woman carrying an urn of water on her head to the right with a hunting party chasing a stag with attendant dogs ‘in the chequered shade’ to the left. The high viewpoint, looking down on an Italianate landscape, and the combination of light and shade is a typical feature of Palmer’s work of the period.

The son of a bookseller, Samuel Palmer lost his mother at an early age and was raised by a nurse, who introduced him to poetry and, in particular, the works of John Milton, for whom he was to have a lifelong passion. His only artistic training came in the drawing lessons he took as a youth, and it is due largely to a number of early encounters with other artists that his style developed. In 1822 he met John Linnell and, through him, was introduced to William Blake two years later. Both artists were to be formative influences on the young Palmer, with Blake, in particular, becoming a mentor and lifelong inspiration. Palmer’s devotion to landscape is evident from his earliest works, and by the second half of the 1820s he had begun to produce richly worked scenes of the countryside around Dulwich in London, treated as a kind of mysterious, fruitful and dreamlike garden.

This ‘visionary’ approach to the pastoral English landscape found its fullest expression when Palmer was living in the village of Shoreham in Kent, where he settled in 1826. The highly finished paintings and drawings of the Shoreham period, in the late 1820s and early 1830s, are regarded as the peak of Palmer’s early career. Painted and drawn in a rich combination of media, and characterized by an intensity of imagery and sentiment, his Shoreham works went against much of what was conventional in the landscape art of the day. (As David Blayney Brown has noted, ‘The inspired fantasy of Palmer’s Shoreham landscapes is unique in English art and can be matched only in the work of continental Romantics like Caspar David Friedrich and Philipp Otto Runge.’ At Shoreham, Palmer was associated with a small group of like-minded artists, including George Richmond and Edward Calvert, who called themselves ‘The Ancients’, but none were quite so committed to this radical vision of landscape as he was.

This resolutely single-minded and somewhat uncommercial approach could not last, however, and Palmer’s style began to change in the mid 1830s. He moved back to London and began travelling further afield, to Devon, Somerset and North Wales, in search of landscapes to paint. Following his marriage to Linnell’s daughter Hannah in 1837, and a two year honeymoon in Italy, Palmer’s work became distinguished by a brightness and clarity inspired by the light of the Mediterranean. The finished Italianate landscapes that he produced over the next three decades, executed in a rich technique of watercolour, gouache and gum arabic, are among his most attractive and appealing works.

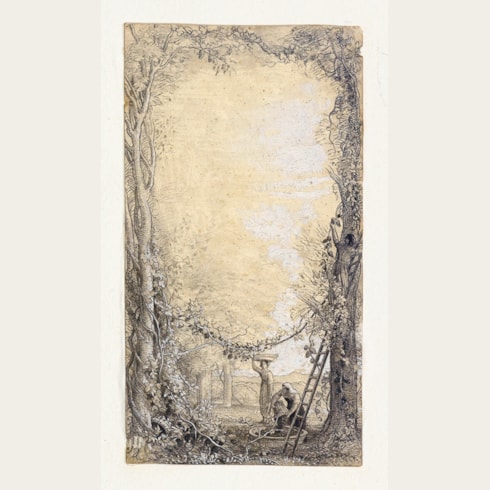

In 1843 Palmer was elected an Associate of the Old Water-Colour Society, becoming a full member in 1854, and although he exhibited there annually, he found few patrons and had to work as a drawing-master to supplement his income. In 1865, however, he received his most important commission, for a series of very large watercolours illustrating Milton’s poems L’Allegro and Il Penseroso, from the solicitor Leonard Rowe Valpy. Palmer worked on these impressive watercolours over the next sixteen years until his death, and they account for some of his finest late work. He also produced a series of largely monochrome drawings, in pencil, charcoal, chalk, watercolour and ink, which were intended to illustrate his own translation of Virgil’s Eclogues. His skill as a draughtsman never faltered and was much admired into his old age; indeed ‘by the end of his life he was as effective – if less widely acknowledged – a master of bravura watercolour as any of his exhibiting contemporaries.’

Provenance

Walker’s Galleries, London, in 1952

Probably acquired from them by a private collector

Thence by descent until 2010.

Literature

‘Society of Painters in Water Colors’, The Building News, 10 May 1861, p.388; Alfred Herbert Palmer, Samuel Palmer: A Memoir, London, 1882, p.87; Alfred Herbert Palmer, The Life and Letters of Samuel Palmer, Painter and Etcher, London, 1892, [1972 ed.], p.411, no.105; Raymond Lister, Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of Samuel Palmer, New York, 1988, p.189, no.586 (as ‘Untraced since 1861’).

Exhibition

London, Society of Painters in Water-colours, 1861, no.133; London, Walker’s Galleries, 48th Annual Exhibition of Early English Water-Colours, 1952, no.85 (as Noon – Resting Time).