Jacopo TINTORETTO

(Venice 1519 - Venice 1594)

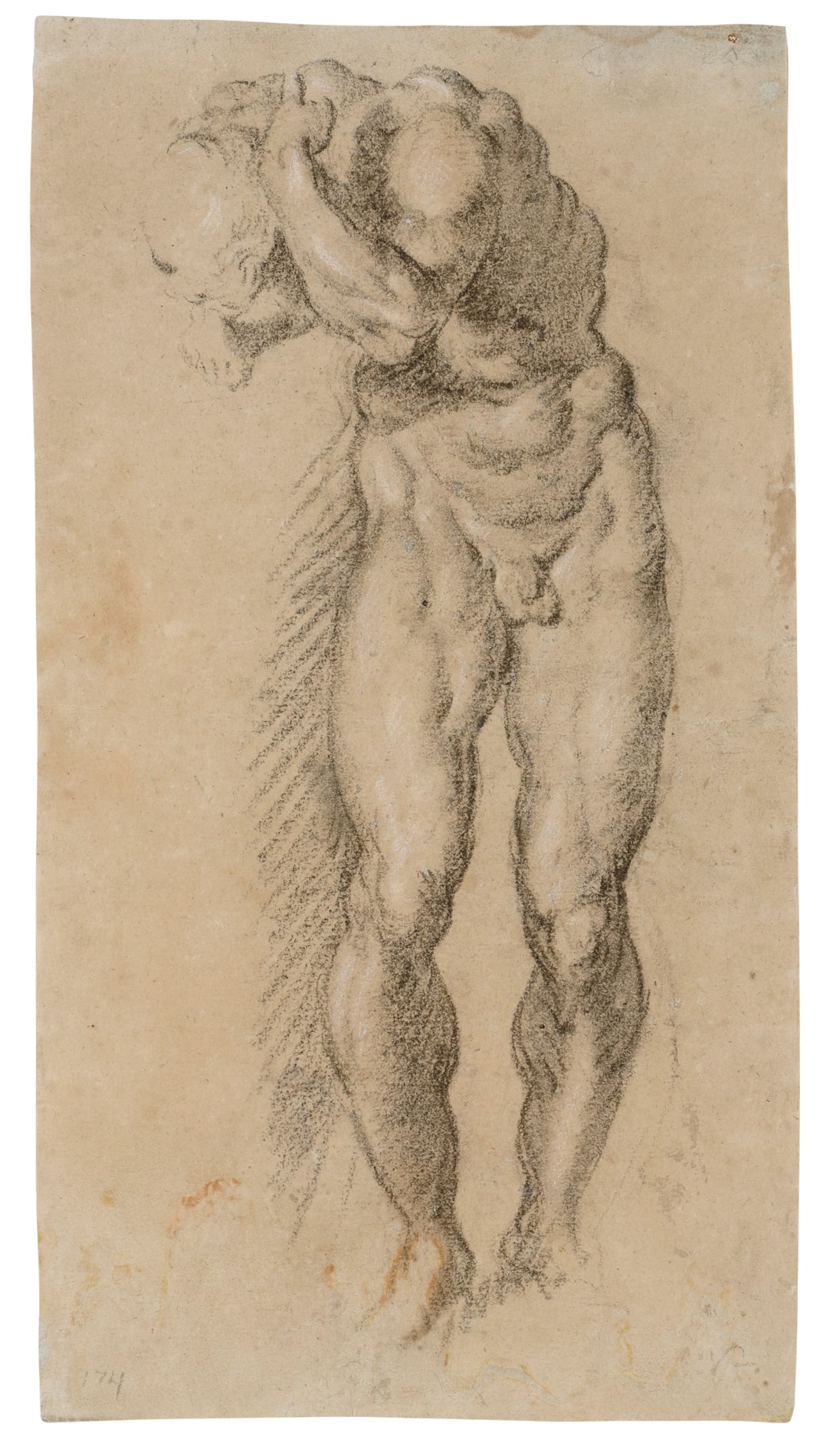

Study of a Male Nude

Sold

Black chalk, with touches of white chalk, on light blue paper faded to light brown.

Numbered 174 at the lower left.

Inscribed Tintoretto / B.B. on the verso.

403 x 215 mm. (15 7/8 x 8 1/2 in.)

Numbered 174 at the lower left.

Inscribed Tintoretto / B.B. on the verso.

403 x 215 mm. (15 7/8 x 8 1/2 in.)

Tintoretto established a lifelong practice of making drawings of the male nude, either from posed models in the studio or after antique sculptures and models by the famous sculptors of his day, notably Michelangelo. In his biography of the artist, Carlo Ridolfi noted of Tintoretto that ‘he set himself…to draw the living model in all sorts of attitudes which he endowed with a grace of movement, drawing from them an endless variety of foreshortenings.’ At the same time, a large proportion of Tintoretto’s surviving drawings are studies after sculpture. In his book Il Riposo, published in 1584, ten years before Tintoretto’s death, Raffaello Borghini wrote that the artist made drawn copies after sculptures by Jacopo Sansovino, Michelangelo and Giambologna, while Ridolfi adds that he acquired several casts and sculptural models, often at considerable expense. That Tintoretto owned a large collection of casts and clay modelli after antique and Renaissance sculptures is evidenced by the fact that they are specifically mentioned, as ‘rilievi del studio’, in the will of his son Domenico, drawn up in 1630.

Modern scholarship has generally dated Tintoretto’s drawings after sculptural models to the late 1540s and the 1550s. As the artist’s biographer Ridolfi noted, ‘these [sculptures] he studied intensively, making an infinite number of drawings of them by the light of an oil lamp, so that he could compose in a powerful and solidly modelled manner by means of those strong shadows cast by the lamp…reproducing them on colored paper with charcoal and watercolor and highlighting them with chalk and white lead’, adding that he sometimes hung them from the ceiling to study the effects of foreshortening. Tintoretto seems to have drawn this small group of sculptures obsessively, from different perspectives and in different lighting conditions. As more recent scholars have written of Tintoretto, ‘For the sake of drawing, which means without regard to a picture to be prepared by the drawing, he drew only from casts from the antique or from other statues...striving for the understanding of foreshortened parts as plastic values, and for the rendering of sharp light and deep shadow in their effects.’ This particularly three-dimensional way of studying the figure served Tintoretto well in his drawings, and in the paintings for which they were preparatory.

The present sheet is a fine and characteristic example of Tintoretto’s vigorous draughtsmanship, with its particular concentration on the musculature of the torso and legs, strong contours, and the delicate play of light and shadow across the body. (The lack of attention paid to the head, hands or feet is also typical of the artist. As Roger Rearick has noted, ‘Jacopo Tintoretto appears, with ample justification, to have trusted his penetrating understanding of the human body in action when it came to details such as hands, feet, and extremities in general.’) Modelled with confident strokes of black chalk and white chalk highlights, the drawing may be added to a small group of chalk studies by Tintoretto which are drawn from a small sculptural model of a stooped figure known as Atlas; possibly to be identified with a bronze statuette of an old man attributed to Jacopo Sansovino and today in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. This group of drawings by Tintoretto ‘show various views of a muscular man bowed in an attitude of exertion, with his limbs bent. The right arm ends in a clenched fist which, possibly, was intended to hold a supporting staff; he left hand is raised above the lowered head, as if to carry an invisible burden.’

Unlike the large groups of drawings by Tintoretto after some other sculptures and statuettes, relatively few studies after this particular nude Atlas figure are known. Stylistically comparable drawings of the Atlas statuette, with his left arm and hand against his head, are in the Uffizi in Florence and formerly in the Franz Koenigs collection and now in the Pushkin Museum. A double-sided sheet with several black chalk studies of the same statuette is in the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, while a handful of other drawings after this model, by Tintoretto or his members of his studio, are known.

The precise pose of the male nude in this drawing is repeated in what has been regarded as a rare pen drawing by Tintoretto; a study of Saint Christopher formerly in the collection of Jacques Petithory and now in the Musée Bonnat-Helleu in Bayonne. This type of muscular male nude also occurs throughout Tintoretto’s painted oeuvre. Similarly posed nude figures appear, for example, in two paintings of scenes from the life of Saint Roch in the Venetian church of San Rocco and in the large Crucifixion of 1565 in the adjacent Scuola di San Rocco.

Drawings such as the present sheet are a testament to Tintoretto’s lifelong study of the male nude, and to the particular influence of Michelangelo on his art. The practice of drawing from sculptures or statuettes, typified by a study such as this, as one scholar has written, ‘reveal a profound understanding of the expressive intensity and power of the source, whether by Michelangelo or classical antiquity. With a speed of hand rarely equalled in its expressive value, Tintoretto captures a powerful vision of musculature strained by vigorous action to the point where the rippling anatomy seems barely contained by the outlining contours.’

Modern scholarship has generally dated Tintoretto’s drawings after sculptural models to the late 1540s and the 1550s. As the artist’s biographer Ridolfi noted, ‘these [sculptures] he studied intensively, making an infinite number of drawings of them by the light of an oil lamp, so that he could compose in a powerful and solidly modelled manner by means of those strong shadows cast by the lamp…reproducing them on colored paper with charcoal and watercolor and highlighting them with chalk and white lead’, adding that he sometimes hung them from the ceiling to study the effects of foreshortening. Tintoretto seems to have drawn this small group of sculptures obsessively, from different perspectives and in different lighting conditions. As more recent scholars have written of Tintoretto, ‘For the sake of drawing, which means without regard to a picture to be prepared by the drawing, he drew only from casts from the antique or from other statues...striving for the understanding of foreshortened parts as plastic values, and for the rendering of sharp light and deep shadow in their effects.’ This particularly three-dimensional way of studying the figure served Tintoretto well in his drawings, and in the paintings for which they were preparatory.

The present sheet is a fine and characteristic example of Tintoretto’s vigorous draughtsmanship, with its particular concentration on the musculature of the torso and legs, strong contours, and the delicate play of light and shadow across the body. (The lack of attention paid to the head, hands or feet is also typical of the artist. As Roger Rearick has noted, ‘Jacopo Tintoretto appears, with ample justification, to have trusted his penetrating understanding of the human body in action when it came to details such as hands, feet, and extremities in general.’) Modelled with confident strokes of black chalk and white chalk highlights, the drawing may be added to a small group of chalk studies by Tintoretto which are drawn from a small sculptural model of a stooped figure known as Atlas; possibly to be identified with a bronze statuette of an old man attributed to Jacopo Sansovino and today in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. This group of drawings by Tintoretto ‘show various views of a muscular man bowed in an attitude of exertion, with his limbs bent. The right arm ends in a clenched fist which, possibly, was intended to hold a supporting staff; he left hand is raised above the lowered head, as if to carry an invisible burden.’

Unlike the large groups of drawings by Tintoretto after some other sculptures and statuettes, relatively few studies after this particular nude Atlas figure are known. Stylistically comparable drawings of the Atlas statuette, with his left arm and hand against his head, are in the Uffizi in Florence and formerly in the Franz Koenigs collection and now in the Pushkin Museum. A double-sided sheet with several black chalk studies of the same statuette is in the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, while a handful of other drawings after this model, by Tintoretto or his members of his studio, are known.

The precise pose of the male nude in this drawing is repeated in what has been regarded as a rare pen drawing by Tintoretto; a study of Saint Christopher formerly in the collection of Jacques Petithory and now in the Musée Bonnat-Helleu in Bayonne. This type of muscular male nude also occurs throughout Tintoretto’s painted oeuvre. Similarly posed nude figures appear, for example, in two paintings of scenes from the life of Saint Roch in the Venetian church of San Rocco and in the large Crucifixion of 1565 in the adjacent Scuola di San Rocco.

Drawings such as the present sheet are a testament to Tintoretto’s lifelong study of the male nude, and to the particular influence of Michelangelo on his art. The practice of drawing from sculptures or statuettes, typified by a study such as this, as one scholar has written, ‘reveal a profound understanding of the expressive intensity and power of the source, whether by Michelangelo or classical antiquity. With a speed of hand rarely equalled in its expressive value, Tintoretto captures a powerful vision of musculature strained by vigorous action to the point where the rippling anatomy seems barely contained by the outlining contours.’

Jacopo Comin, who earned his nickname Tintoretto as a result of his father’s profession as a tintore, or cloth dyer, is thought to have trained in the studio of Titian. By the end of the 1540’s he had established a large and busy workshop of his own in Venice, and throughout his career he rarely left the city. His oeuvre was extensive, comprising altarpieces and other paintings for Venetian churches, vast pictorial cycles for confraternities or scuole, and narrative pictures for the Palazzo Ducale and other civic buildings, as well as portraits and easel pictures for private patrons in Venice and abroad. He was a gifted and prolific draughtsman, with a particular interest in the study of the male nude form. After his death in 1594, his drawings seem to have been retained in his workshop, run by his sons Domenico and Marco, before eventually coming into the possession of his son-in-law, Sebastian Casser.

Provenance

Probably by descent in the Tintoretto studio to his son-in-law, Sebastian Casser, until c.1648

Otto Wertheimer, Paris

Purchased from him in 1948 by a private collector

Thence by descent to a private collection, Switzerland

Stephen Ongpin Fine Art, London, in 2007

Private collection.

Literature

Horace Wood Brock, Martin P. Levy and Clifford S. Ackley, Splendor and Elegance: European Decorative Arts and Drawings from the Horace Wood Brock Collection, exhibition catalogue, Boston, 2009, p.157, no.117, illustrated p.117; Sebastian Smee, “? = Beauty”, The Boston Globe, 22 February 2009.

Exhibition

Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Splendor and Elegance: European Decorative Arts and Drawings from the Horace Wood Brock Collection, 2009, no.117.