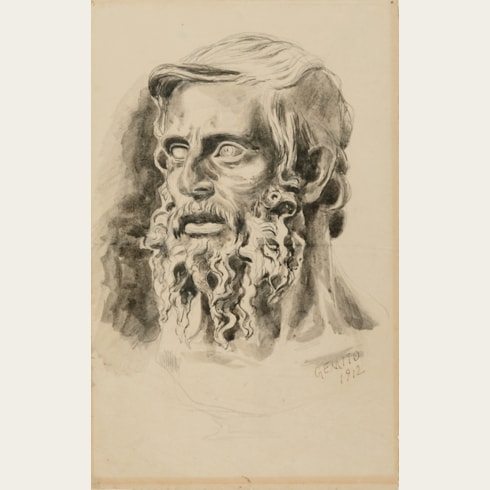

Vincenzo GEMITO

(Naples 1852 - Naples 1929)

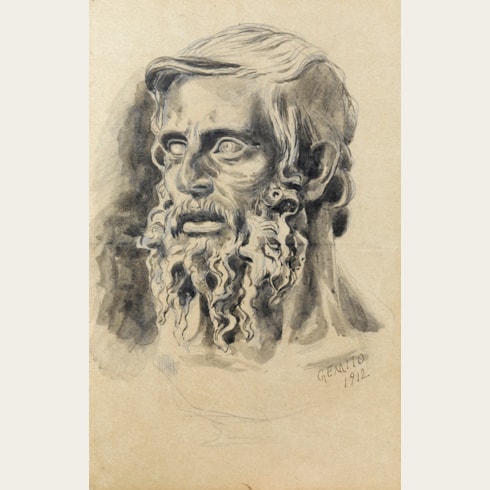

Head of a Bearded Old Man (The Philosopher)

Signed GEMITO at the lower right.

592 x 433 mm. (23 3/8 x 17 in.)

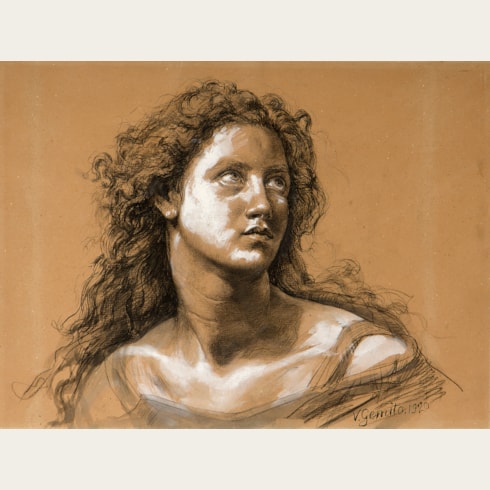

218 x 138 mm. (8 5/8 x 5 3/8 in.)

The model for The Philosopher was almost certainly the artist’s stepfather, Francesco Jadicicco, known as ‘Masto Ciccio’, who married Gemito’s mother in 1875. Masto Ciccio appears in many of Gemito’s drawings2, and posed for several sculptures. He also worked for some time in the artist’s foundry, where he helped to produce the bronzes made there between 1883 and 1886, including The Philosopher. As has been noted, therefore, ‘this bust is thus a double homage, paying tribute to both the artistic verisimilitude achieved by ancient sculptors and the timeless vision of this paternal figure. Perhaps because the bust is clearly based on an ancient prototype, Gemito’s personal intervention in the unruly flow of hair and the hyperintense expression is even more noticeable than if this had been a direct portrait in a contemporary style.’

Gemito’s masterful sculpture of The Philosopher has been described by one recent scholar as a work of ‘intensely eloquent realism...Unlike its classical antecedents, Gemito’s bust has the imprint not only of a carefully rendered physiognomy but of a psychological penetration that lays open the sitter’s whole biography.’

After Antonio Canova, Vincenzo Gemito was perhaps the foremost Italian sculptor of the 19th century. (Indeed, he was described as such by the 20th century sculptor Giacomo Manzù.) A precocious talent, he received his early training as a young boy in the studios of the sculptors Emmanuele Caggiano and Stanislao Lista. In 1868 the sixteen-year old Gemito exhibited a sculpture at the Promotrice di Belle Arti in Naples that attracted the attention of the King of Italy, Vittorio Emmanuele II, who acquired a bronze cast of the work for the palace at Capodimonte. It was also at this time that the young sculptor gained the support of the leading Neapolitan painter Domenico Morelli. Between 1877 and 1880 Gemito lived in Paris, where he became a close friend of the French painter and sculptor Ernest Meissonier. At the Salon of 1877 he exhibited his sculpture of a Neapolitan Fisherboy to considerable critical acclaim, earning a number of portrait commissions as a result.

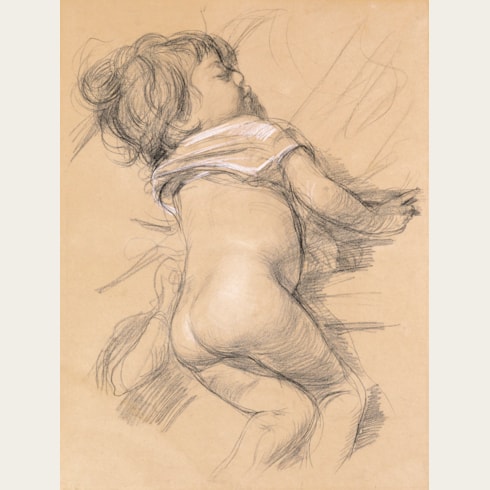

Gemito continued to participate in the Paris Salons after his return to Naples, winning the Grand Prix for sculpture in 1889 and a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle the following year. He also took part in the inaugural (and only) exhibition of the Société Internationale de Peintres et Sculpteurs at the Galerie Georges Petit in 1882, alongside John Singer Sargent, Giovanni Boldini, Jean Béraud and others. In 1883, with the financial support of the Belgian industrialist Baron Oscar de Mesnil, Gemito was able to set up his own foundry, located on the via Mergellina in Naples, although it was to cease production three years later. Around 1887, after he began to experience bouts of mental illness, Gemito gave up sculpture almost entirely, and spent much of next eighteen years as a recluse in his own home. He nevertheless continued to produce a large number of drawings, mostly portraits of friends and colleagues, as well as studies of street urchins, Neapolitan girls and other city folk. It was not until around 1909 that Gemito again took up sculpture full time, and it was in this later period of his career that he produced some of his finest work in bronze, executed with a delicacy and fineness of detail ultimately derived from his drawings.

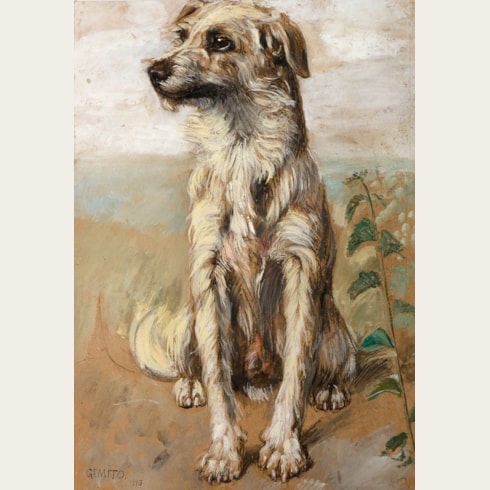

Gemito was an immensely gifted draughtsman, and produced a large number of figure and portrait studies in pen, chalk, pastel and watercolour. His drawings were greatly admired throughout his career, and were avidly collected by his contemporaries. (Already in his lifetime, his drawings had been likened to those of the sculptors Auguste Rodin and Constantin Meunier by one Italian scholar, in an article published in 1916.) Yet until relatively recently Gemito’s drawings have remained little known outside Italy, and it may be argued that he deserves to be recognized as not only one of the most significant sculptors of the period, but also one of its most gifted and distinctive draughtsmen.

Provenance

Literature