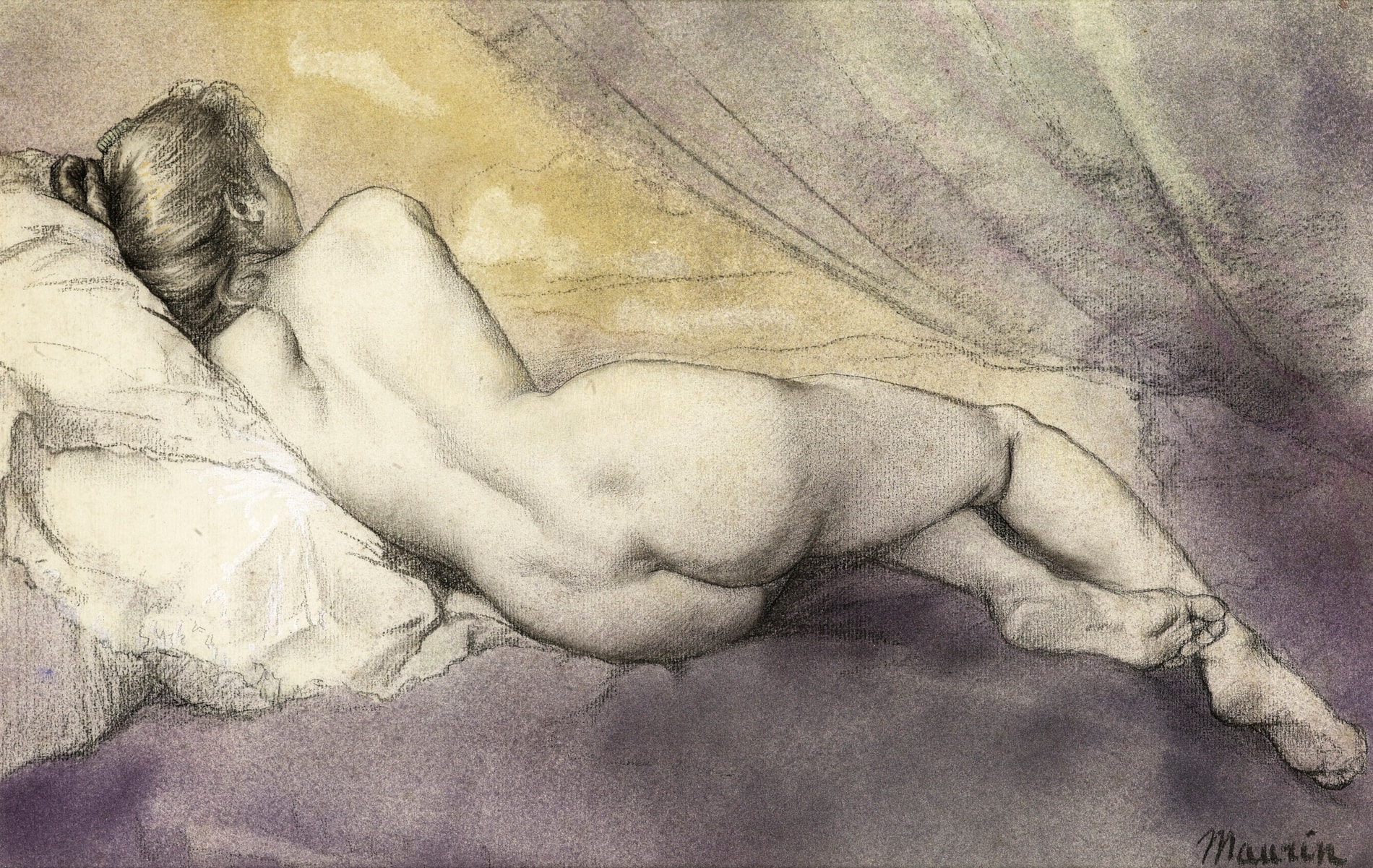

Charles MAURIN

(Le Puy-en-Velay 1856 - Grasse 1914)

A Reclining Female Nude

Sold

Black chalk, pencil, watercolour and pastel, with touches of white heightening, on paper.

Signed Maurin in black chalk at the lower right.

316 x 480 mm. (12 1/2 x 18 7/8 in.) [sheet]

Signed Maurin in black chalk at the lower right.

316 x 480 mm. (12 1/2 x 18 7/8 in.) [sheet]

This beautiful and refined drawing is a splendid example of Maurin’s lifelong interest in the depiction of the female nude. Such voluptuous nudes appear in several of his paintings and in many of his prints and drawings. The solitary female nude was, in fact, one of the constant themes of Maurin’s graphic art, and the resulting prints and drawings are among the artist’s most striking and individual works. Like Degas, Maurin was fond of portraying women at intimate moments of their daily routine; ‘The themes of woman at their toilette, dressing, undressing, bathing, drying themselves, brushing their hair, contemplating themselves in front of a mirror are found earlier and less matter of factly in the prints and paintings of Degas and Cassatt.’ As Colin Eisler has further noted, ‘Maurin modernized the voluptuous nudes of the 60’s and 70’s. It was this aspect of his art that so appealed to Degas, who saw Maurin as heir to Ingres’s mastery of the nude.’

Among comparable pastel drawings by Maurin is a study of a young nude girl playing with a doll, in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

Among comparable pastel drawings by Maurin is a study of a young nude girl playing with a doll, in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

Having won the art scholarship known as the Prix Crozatier in 1875, Charles Maurin entered the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, studying with Jules Lefèbvre and Gustave Boulanger, and with Rodolphe Julian at the Académie Julian. He first exhibited at the Salon des Artistes Français in 1882, where he showed a pair of portraits, one of which gained an honourable mention. He continued to exhibit at the Salon des Artistes Français until 1890. He participated in the Salon des Indépendants for the first time in 1887, showing a number of paintings, drawings and engravings that were admired by, among others, Edgar Degas. As an artist, he worked in a variety of styles, the most distinctive being a sort of Symbolism evident in a range of allegorical subjects that he treated.

Maurin had a lifelong interest in the depiction of the female nude, and, like Degas and Mary Cassatt, was fond of portraying women at intimate moments of their daily routine. He also produced a handful of splendid portraits, mainly in the 1880s and 1890s, of friends, patrons and fellow artists including Georges Seurat and Rupert Carabin, as well as drawings and pastels of café, theatre and street scenes. Around 1885 he took up an appointment as a professor at the Académie Julian, where he met Félix Vallotton, who became a close friend. Another good friend was Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, with whom Maurin shared an exhibition in 1893 at the Galerie Boussod et Valadon in Paris. It was there that, at the urging of Degas, the collector Henry Laurent began to acquire Maurin’s work, eventually becoming his foremost patron and collector.

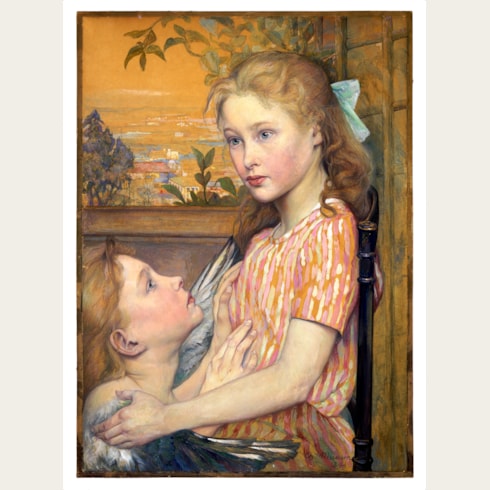

The 1890s found Maurin enjoying a moderately successful career, with one-man shows with Ambroise Vollard in 1895 and at Edmond Sagot in 1899. He received a commission from the State for a painting of Maternité (Motherhood); completed in 1893 and sent to the museum in his native town of Le Puy, the painting was soon regarded as one of the artist’s finest works. The previous year he took part in the inaugural Salon de la Rose + Croix, where he showed one of his largest and most important paintings; a monumental triptych entitled L’Aurore (Dawn). He also contributed works to the Salons de la Rose + Croix of 1895 and 1897. Maurin painted a series of large decorative panels of Tragedy, Dance and Music for the foyer of the municipal theatre in Le Puy in 1893, and for Sarah Bernhardt designed sets and costumes for Edmond Rostand’s La Princess Lointaine in 1895. He visited Holland, Belgium and England, and sent works to Le Libre Esthétique in Brussels in 1896 and 1897, and the Exhibition of International Art in London in 1898. A man of firm anarchist leanings, Maurin produced illustrations for the radical journal Le Temps nouveau, and published portrait prints of the French anarchists Louise Michel and François Koenigstein, known as Ravachol. In 1895 he was also commissioned to provide illustrations for the art and literary journal La Revue Blanche.

After 1900, however, Maurin’s output declined considerably, partly due to ill health, and the last years of his life were spent in Brittany and Provence, where he died in obscurity in 1914. His work was largely forgotten after his death, although a retrospective exhibition was held at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune in Paris in 1921, while a monograph on his work by Ulysse Rouchon was published the following year. Although a significant collection of Maurin’s work is today in the collection of the Musée Crozatier in Le Puy-en-Velay, his paintings and drawings remain little represented in museums outside France.

As a draughtsman, Charles Maurin was equally adept in pastel, chalk and pencil, and was highly regarded by critics, collectors and fellow artists; his drawings were, for example, particularly esteemed by Degas, who compared his draughtsmanship to that of his own great hero, Ingres. An innovative artist, he invented a method of using an atomizer to spray pigment onto the surface of the paper to create what he termed ‘peintures au vaporisateur’; large, atmospheric watercolour landscapes of great subtlety and beauty. Maurin is perhaps best known today, however, as a gifted and prolific printmaker, and played an important role in the revival of colour etching and wood engraving in the 1890s. Like his paintings, many of his prints focus on the female nude, or the theme of mothers and children, and account for some of the artist’s most striking and individual works. Maurin also developed a number of new techniques and processes, particularly with regard to printing in colour. Some of his prints were published in editions of ten or less, however, and much of his graphic work remains very rare today.

Although long forgotten or ignored after his death, Charles Maurin’s eclectic oeuvre as a painter, printmaker and draughtsman remains one of the most distinctive of any artist in France in the late 19th century. The French scholar Jacques Foucart, writing in 1979, succinctly described the artist as ‘that curious and libertarian figure, so typical of the effervescent Paris of the Belle Epoque, an engraver of social customs comparable with Louis Legrand, a perfectionist and an inventive technician, a sensitive draughtsman à la Besnard, a friend of Lautrec and Valloton. He created some of the most extravagant humanitarian and ‘socialist’ visions of the fin-de-siècle, which he treated in a flexible and decorative ‘graphisme’ in the manner of Eugène Grasset, or even of De Feure...That an artist of such intriguing qualities – even though, as engraver of nudes, he does at times become rather tiresomely vulgar and commercial – and so representative of a period that was hungry to explore everything (it is often said that all modern art was contained in the years before 1914), has been the subject of neither an exhibition, since that of 1921 at Bernheim’s, nor of a monograph, certainly sets one thinking about the vagaries of Taste and about the nature of the present fashion for the art of 1900.’ In recent years, however, a revival of interest in Maurin’s remarkable body of work culminated in a major monographic exhibition, entitled Charles Maurin, un Symboliste du Réel, at the Musée Crozatier in the artist’s native town of Le Puy-en-Valey in 2006.

Maurin had a lifelong interest in the depiction of the female nude, and, like Degas and Mary Cassatt, was fond of portraying women at intimate moments of their daily routine. He also produced a handful of splendid portraits, mainly in the 1880s and 1890s, of friends, patrons and fellow artists including Georges Seurat and Rupert Carabin, as well as drawings and pastels of café, theatre and street scenes. Around 1885 he took up an appointment as a professor at the Académie Julian, where he met Félix Vallotton, who became a close friend. Another good friend was Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, with whom Maurin shared an exhibition in 1893 at the Galerie Boussod et Valadon in Paris. It was there that, at the urging of Degas, the collector Henry Laurent began to acquire Maurin’s work, eventually becoming his foremost patron and collector.

The 1890s found Maurin enjoying a moderately successful career, with one-man shows with Ambroise Vollard in 1895 and at Edmond Sagot in 1899. He received a commission from the State for a painting of Maternité (Motherhood); completed in 1893 and sent to the museum in his native town of Le Puy, the painting was soon regarded as one of the artist’s finest works. The previous year he took part in the inaugural Salon de la Rose + Croix, where he showed one of his largest and most important paintings; a monumental triptych entitled L’Aurore (Dawn). He also contributed works to the Salons de la Rose + Croix of 1895 and 1897. Maurin painted a series of large decorative panels of Tragedy, Dance and Music for the foyer of the municipal theatre in Le Puy in 1893, and for Sarah Bernhardt designed sets and costumes for Edmond Rostand’s La Princess Lointaine in 1895. He visited Holland, Belgium and England, and sent works to Le Libre Esthétique in Brussels in 1896 and 1897, and the Exhibition of International Art in London in 1898. A man of firm anarchist leanings, Maurin produced illustrations for the radical journal Le Temps nouveau, and published portrait prints of the French anarchists Louise Michel and François Koenigstein, known as Ravachol. In 1895 he was also commissioned to provide illustrations for the art and literary journal La Revue Blanche.

After 1900, however, Maurin’s output declined considerably, partly due to ill health, and the last years of his life were spent in Brittany and Provence, where he died in obscurity in 1914. His work was largely forgotten after his death, although a retrospective exhibition was held at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune in Paris in 1921, while a monograph on his work by Ulysse Rouchon was published the following year. Although a significant collection of Maurin’s work is today in the collection of the Musée Crozatier in Le Puy-en-Velay, his paintings and drawings remain little represented in museums outside France.

As a draughtsman, Charles Maurin was equally adept in pastel, chalk and pencil, and was highly regarded by critics, collectors and fellow artists; his drawings were, for example, particularly esteemed by Degas, who compared his draughtsmanship to that of his own great hero, Ingres. An innovative artist, he invented a method of using an atomizer to spray pigment onto the surface of the paper to create what he termed ‘peintures au vaporisateur’; large, atmospheric watercolour landscapes of great subtlety and beauty. Maurin is perhaps best known today, however, as a gifted and prolific printmaker, and played an important role in the revival of colour etching and wood engraving in the 1890s. Like his paintings, many of his prints focus on the female nude, or the theme of mothers and children, and account for some of the artist’s most striking and individual works. Maurin also developed a number of new techniques and processes, particularly with regard to printing in colour. Some of his prints were published in editions of ten or less, however, and much of his graphic work remains very rare today.

Although long forgotten or ignored after his death, Charles Maurin’s eclectic oeuvre as a painter, printmaker and draughtsman remains one of the most distinctive of any artist in France in the late 19th century. The French scholar Jacques Foucart, writing in 1979, succinctly described the artist as ‘that curious and libertarian figure, so typical of the effervescent Paris of the Belle Epoque, an engraver of social customs comparable with Louis Legrand, a perfectionist and an inventive technician, a sensitive draughtsman à la Besnard, a friend of Lautrec and Valloton. He created some of the most extravagant humanitarian and ‘socialist’ visions of the fin-de-siècle, which he treated in a flexible and decorative ‘graphisme’ in the manner of Eugène Grasset, or even of De Feure...That an artist of such intriguing qualities – even though, as engraver of nudes, he does at times become rather tiresomely vulgar and commercial – and so representative of a period that was hungry to explore everything (it is often said that all modern art was contained in the years before 1914), has been the subject of neither an exhibition, since that of 1921 at Bernheim’s, nor of a monograph, certainly sets one thinking about the vagaries of Taste and about the nature of the present fashion for the art of 1900.’ In recent years, however, a revival of interest in Maurin’s remarkable body of work culminated in a major monographic exhibition, entitled Charles Maurin, un Symboliste du Réel, at the Musée Crozatier in the artist’s native town of Le Puy-en-Valey in 2006.

Provenance

Probably the vente d’atelier Charles Maurin, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, 22 November 1998, lot 220 (‘Femme nue allongée vue de dos. Pastel, craie, aquarelle, signé en bas à droite. 28 x 45,5 cm.’).