Alberto GIACOMETTI

(Borgonovo 1902 - Chur 1966)

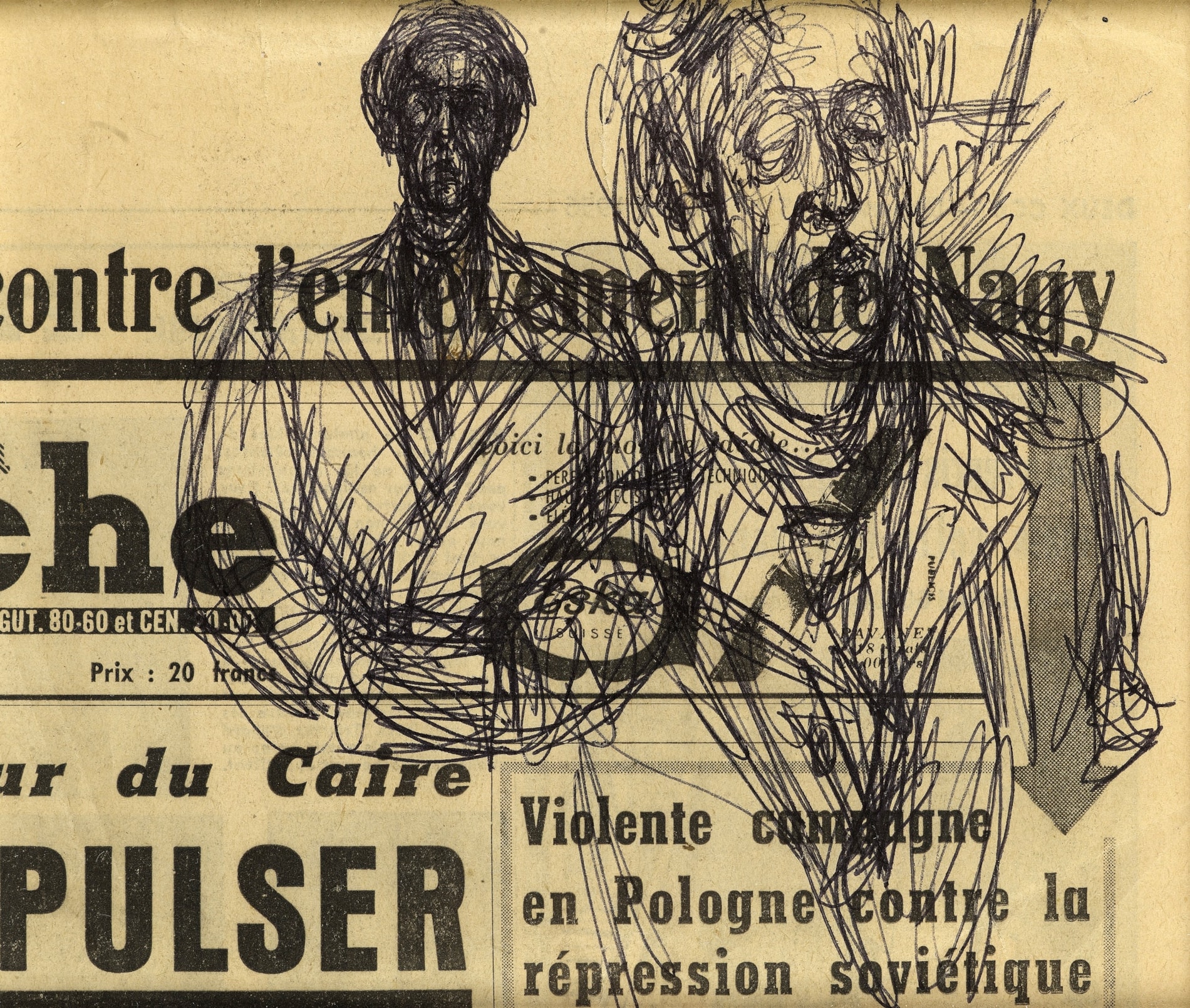

Portrait of Isaku Yanaihara

Sold

Ballpoint pen and black ink on a corner of a newspaper (the Journal du Dimanche, dated 25 November 1956).

164 x 199 mm. (6 1/2 x 7 7/8 in.)

164 x 199 mm. (6 1/2 x 7 7/8 in.)

The present sheet depicts one of Giacometti’s most significant portrait subjects. A Japanese professor of philosophy, Isaku Yanaihara (1918-1989) arrived in Paris in 1954 on a scholarship to study at the Sorbonne, and soon befriended a number of writers and artists. He first met Giacometti at the Café des Deux Magots in Paris in November 1955, and visited the artist’s studios a number of times. The two men developed a close friendship, and in the fall of 1956 Giacometti asked Yanaihara to pose for him. Their first session took place on October 6th, 1956, with Giacometti first working on a handful of drawings of his new model, although within a day or two he had begun a painting on canvas.

As James Lord has noted of Yanaihara, ‘With a large head, strong jaw, broad, high forehead, and small but piercing eyes in well-defined sockets, he was handsome but not imposing. As a model he came close to being ideal, because in addition to the striking singularity of his features and the lively concentration of his gaze, he was capable of remaining for long periods absolutely motionless. The essential aspect of his suitability was friendship, as Giacometti needed the emotional participation of his model in an act which called for extraordinary unselfishness but offered a rare measure of intimacy.’ Over the next few years, the professor was to sit for several paintings, a number of drawings and two sculpted busts. Yanaihara kept several journals recording their conversations, which became the basis of a Japanese monograph on Giacometti, published in Tokyo in 1958. He also became friendly with the artist’s wife Annette, and the two became lovers, with Giacometti’s knowledge and consent.

Yanaihara visited Paris every year but one between 1955 and 1961, and posed for Giacometti countless times; indeed over this period he sat for the artist for a total of some 230 days in all. The two men would meet every day for lunch, after which Yanaihara would patiently pose for several hours in the afternoon and evening. (In a letter written to Pierre Matisse in October 1956, shortly after Yanaihara had begun posing for him, the artist praised his ‘Japanese friend who poses unmoving, like a statue.’) As Lord has written, ‘The intimacy between the two men grew intense, began to have the aspect of a passionate attachment...[Giacometti] continued laboriously to paint portraits of the philosopher, each one a challenge to renew the infinitely changeable inferences of vision. This determination to prove that seeing can be believing became concentrated entirely on likenesses of Yanaihara...Yanaihara’s portraits had become essential to a sense of enriching self-discovery in his work.’

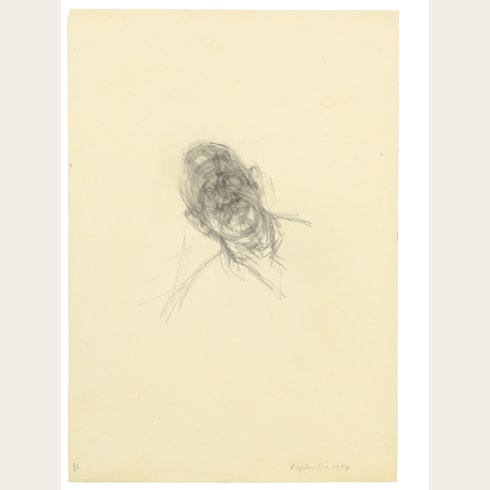

This rapid pen sketch, drawn on the corner of a newspaper, dates from the period near the end of 1956 when Giacometti was struggling with his first portraits of Yanaihara; a series of three paintings which he reworked obsessively over a period of several weeks. As one scholar has written of this time, ‘At the end of the year, while painting a portrait of Isaku Yanaihara, Giacometti found himself unable to capture the professor’s likeness. The artist sank into frantic despair, neglecting sculpture to repaint Yanaihara’s image so many times that resemblance and style became mired in a miasma of grey paint. In a panic, Giacometti focused only on his model’s head and eyes, until those areas on the canvas grew thick with layered lines that still faded into an undefined grey periphery. This crisis lasted well after Yanaihara’s departure: images of Diego and Annette from 1957 and 1958 suffer from a similar lack of definition. Painting became a struggle between form and formlessness, usually resulting in a small figure apparently isolated at a distance in an undefined world...Giacometti needed desperately to resolve this impasse, which he did partly by rationalising the new style and partly by continuing to work his way through the morass to a more solid definition of forms (one reason why he needed to bring Yanaihara back from Japan in the subsequent summers).’

As James Lord has noted of Yanaihara, ‘With a large head, strong jaw, broad, high forehead, and small but piercing eyes in well-defined sockets, he was handsome but not imposing. As a model he came close to being ideal, because in addition to the striking singularity of his features and the lively concentration of his gaze, he was capable of remaining for long periods absolutely motionless. The essential aspect of his suitability was friendship, as Giacometti needed the emotional participation of his model in an act which called for extraordinary unselfishness but offered a rare measure of intimacy.’ Over the next few years, the professor was to sit for several paintings, a number of drawings and two sculpted busts. Yanaihara kept several journals recording their conversations, which became the basis of a Japanese monograph on Giacometti, published in Tokyo in 1958. He also became friendly with the artist’s wife Annette, and the two became lovers, with Giacometti’s knowledge and consent.

Yanaihara visited Paris every year but one between 1955 and 1961, and posed for Giacometti countless times; indeed over this period he sat for the artist for a total of some 230 days in all. The two men would meet every day for lunch, after which Yanaihara would patiently pose for several hours in the afternoon and evening. (In a letter written to Pierre Matisse in October 1956, shortly after Yanaihara had begun posing for him, the artist praised his ‘Japanese friend who poses unmoving, like a statue.’) As Lord has written, ‘The intimacy between the two men grew intense, began to have the aspect of a passionate attachment...[Giacometti] continued laboriously to paint portraits of the philosopher, each one a challenge to renew the infinitely changeable inferences of vision. This determination to prove that seeing can be believing became concentrated entirely on likenesses of Yanaihara...Yanaihara’s portraits had become essential to a sense of enriching self-discovery in his work.’

This rapid pen sketch, drawn on the corner of a newspaper, dates from the period near the end of 1956 when Giacometti was struggling with his first portraits of Yanaihara; a series of three paintings which he reworked obsessively over a period of several weeks. As one scholar has written of this time, ‘At the end of the year, while painting a portrait of Isaku Yanaihara, Giacometti found himself unable to capture the professor’s likeness. The artist sank into frantic despair, neglecting sculpture to repaint Yanaihara’s image so many times that resemblance and style became mired in a miasma of grey paint. In a panic, Giacometti focused only on his model’s head and eyes, until those areas on the canvas grew thick with layered lines that still faded into an undefined grey periphery. This crisis lasted well after Yanaihara’s departure: images of Diego and Annette from 1957 and 1958 suffer from a similar lack of definition. Painting became a struggle between form and formlessness, usually resulting in a small figure apparently isolated at a distance in an undefined world...Giacometti needed desperately to resolve this impasse, which he did partly by rationalising the new style and partly by continuing to work his way through the morass to a more solid definition of forms (one reason why he needed to bring Yanaihara back from Japan in the subsequent summers).’

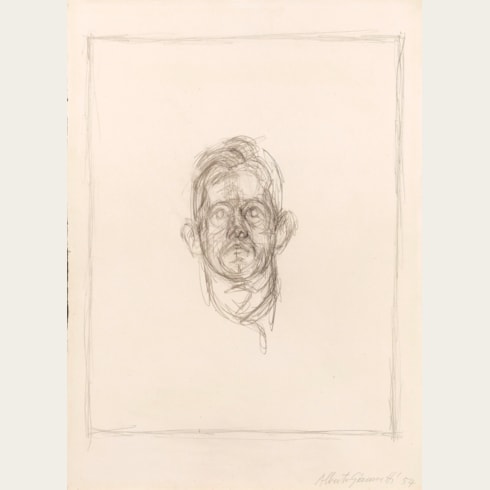

Alberto Giacometti regarded drawing as the foundation of all of his artistic activities. As his friend and biographer James Lord recalled, ‘“What I believe,” Alberto once said, “is that whether it be a question of sculpture or of painting, it is in fact only drawing that counts. One must cling solely, exclusively to drawing. If one could master drawing, all the rest would be possible.”’ Similarly, the art historian Michael Peppiatt has noted that ‘Throughout his career, drawing remained the most spontaneous and revealing of Giacometti’s very varied forms of expression, a constant diary he kept of the people in his life and the objects which fascinated him...Drawing served him as the most direct way of grasping reality (however evasive), of rehearsing a new concept, or attempting to solve problems which had surfaced in painting or sculpture. Drawing was the universal language, and Giacometti would refer to it as the essential source of his art, the matrix in which all forms originated.’ The artist Francis Bacon was a particular admirer of the drawings of his friend Giacometti, of whom he wrote in 1975, ‘For me Giacometti is not only the greatest draughtsman of our time but among the greatest of all time.’

In the 1950’s Giacometti, who had previously only made portraits of close family members, began to produce portraits of a handful of other individuals with whom he had developed a close relationship, in particular several writers and critics. Jean Genet, Peter Watson, David Sylvester, James Lord and Isaku Yanaihara, as well as the photographer Ernst Scheidegger and the art dealer Marguerite Maeght, all sat for painted portraits by the artist. Many more friends and colleagues appear in Giacometti’s pencil drawings of the 1950’s and 1960’s, including Henri and Pierre Matisse, Aimé Maeght, Jacques Dupin, Igor Stravinsky, Donald Cooper and several others. As has been noted of such portrait drawings, ‘Many of these sheets can be counted among the most intense works Giacometti produced.’

Provenance

André Darricau (Darry Cowl), Neuilly-sur-Seine

Private collection, Paris, until 2011.