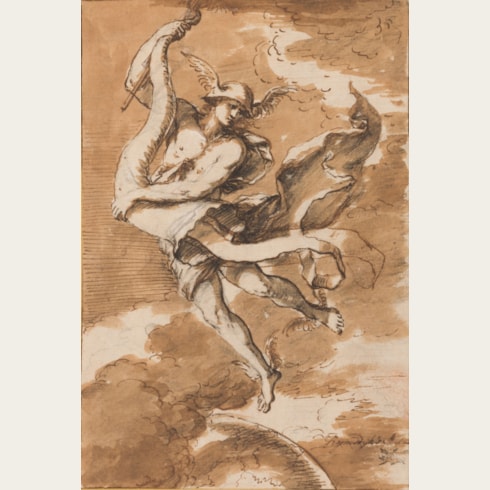

Salvator ROSA

(Arenella 1615 - Rome 1673)

A Standing Halberdier

Pen and brown ink and brown wash, over a black chalk underdrawing.

Laid down on an 18th century (Richardson) mount, inscribed Salvator Rosa at the bottom and with the shelfmark D. inscribed on the reverse.

Further inscribed From the collection of Jonathan Richardson, the Painter in the bottom margin of the mount, and faintly inscribed Lot 120 on the reverse of the mount.

147 x 90 mm. (5 3/4 x 3 1/2 in.)

Laid down on an 18th century (Richardson) mount, inscribed Salvator Rosa at the bottom and with the shelfmark D. inscribed on the reverse.

Further inscribed From the collection of Jonathan Richardson, the Painter in the bottom margin of the mount, and faintly inscribed Lot 120 on the reverse of the mount.

147 x 90 mm. (5 3/4 x 3 1/2 in.)

This is a preparatory study for an etching by Salvator Rosa from his celebrated Figurine series; a group of sixty-two etchings of soldiers, peasants and other figures, depicted either individually or in groups of two, three or more. These etchings, which were published with a dedication to the artist’s friend and patron, the Roman banker and collector Carlo de’ Rossi, can be dated to Rosa’s years in Rome, around 1656-1657.

As Helen Langdon has noted of the Figurine etchings, ‘This series, which has no preconceived theme, was a capriccio, or bravura display of fantasy and improvisation...a dazzling array of figures, a masterful display of variety of pose and mood, of gestures and groupings. Rosa shows warriors standing, walking, beckoning, gesturing, seated on rocks, asleep or shrouded in melancholy; they wear archaicizing dress that blends vaguely antique and Renaissance armour with exotic and imaginative detail, and carry war hammers, maces and swords...to the seventeenth-century viewer they would perhaps have seemed an evocation of the knights and warriors of chivalric romance.’

In every case, the protagonists of Rosa’s Figurine etchings are depicted removed from any context or setting. As Richard Wallace has noted ‘They look as they do because they derive from the drawn and painted figures whose purpose it was to populate Rosa’s landscapes, harbor scenes, and battles and to give these settings life and vivacity by their energetic and varied postures, gestures, and groupings. The Figurine are in a sense extracts from the paintings. It is as if Rosa decided to isolate these figures from the context that brought them into being in order to elevate them to the status of complete works of art in themselves.’

It has been suggested that, apart from helping to spread Rosa’s fame, these Figurine etchings may also have served to rebut the claims, made by the artist’s critics, that he was merely a landscape painter without the ability to depict figures. As Richard Wallace has noted, ‘Rosa was very touchy about his reputation as a figure painter...With the Figurine he undoubtedly meant to show everyone, including his detractors...that he could master the human figure in an almost infinite variety of poses and expressive states.’ Often acquired as a complete set of prints and bound into albums, Rosa’s Figurine etchings remained popular with collectors well into the 18th century. Around forty of Rosa’s preparatory drawings for individual etchings in the Figurine series survive. All are of identical dimensions to the etchings, and in most respects very close to the final print, albeit in reverse.

Other preparatory drawings by Rosa for his Figurine etchings are today in the collections of the Teylers Museum in Haarlem, the Istituto Nazionale per la Grafica in Rome, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Royal Library at Windsor Castle, and elsewhere.

The earliest known owner of this drawing was the English portrait painter, author and connoisseur Jonathan Richardson the Elder (1667-1745), whose collector’s mark is found at the lower right corner of the sheet. Richardson owned a remarkable collection of nearly five thousand drawings, mostly Italian works of the 16th and 17th centuries, assembled over a period of about fifty years. Richardson’s extensive collection was organized by school and date, and the drawings were further classified with a complex system of shelfmarks.

A note on the backing sheet states that the drawing later belonged to an ‘A. Scott Carter’; this may be Alexander Scott Carter (1881-1968), an English-born heraldry artist who settled in Toronto, Canada.

As Helen Langdon has noted of the Figurine etchings, ‘This series, which has no preconceived theme, was a capriccio, or bravura display of fantasy and improvisation...a dazzling array of figures, a masterful display of variety of pose and mood, of gestures and groupings. Rosa shows warriors standing, walking, beckoning, gesturing, seated on rocks, asleep or shrouded in melancholy; they wear archaicizing dress that blends vaguely antique and Renaissance armour with exotic and imaginative detail, and carry war hammers, maces and swords...to the seventeenth-century viewer they would perhaps have seemed an evocation of the knights and warriors of chivalric romance.’

In every case, the protagonists of Rosa’s Figurine etchings are depicted removed from any context or setting. As Richard Wallace has noted ‘They look as they do because they derive from the drawn and painted figures whose purpose it was to populate Rosa’s landscapes, harbor scenes, and battles and to give these settings life and vivacity by their energetic and varied postures, gestures, and groupings. The Figurine are in a sense extracts from the paintings. It is as if Rosa decided to isolate these figures from the context that brought them into being in order to elevate them to the status of complete works of art in themselves.’

It has been suggested that, apart from helping to spread Rosa’s fame, these Figurine etchings may also have served to rebut the claims, made by the artist’s critics, that he was merely a landscape painter without the ability to depict figures. As Richard Wallace has noted, ‘Rosa was very touchy about his reputation as a figure painter...With the Figurine he undoubtedly meant to show everyone, including his detractors...that he could master the human figure in an almost infinite variety of poses and expressive states.’ Often acquired as a complete set of prints and bound into albums, Rosa’s Figurine etchings remained popular with collectors well into the 18th century. Around forty of Rosa’s preparatory drawings for individual etchings in the Figurine series survive. All are of identical dimensions to the etchings, and in most respects very close to the final print, albeit in reverse.

Other preparatory drawings by Rosa for his Figurine etchings are today in the collections of the Teylers Museum in Haarlem, the Istituto Nazionale per la Grafica in Rome, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Royal Library at Windsor Castle, and elsewhere.

The earliest known owner of this drawing was the English portrait painter, author and connoisseur Jonathan Richardson the Elder (1667-1745), whose collector’s mark is found at the lower right corner of the sheet. Richardson owned a remarkable collection of nearly five thousand drawings, mostly Italian works of the 16th and 17th centuries, assembled over a period of about fifty years. Richardson’s extensive collection was organized by school and date, and the drawings were further classified with a complex system of shelfmarks.

A note on the backing sheet states that the drawing later belonged to an ‘A. Scott Carter’; this may be Alexander Scott Carter (1881-1968), an English-born heraldry artist who settled in Toronto, Canada.

A painter, draughtsman and printmaker, as well as an accomplished actor, musician and poet, Salvator Rosa studied in Naples with his brother-in-law Francesco Fracanzano, as well as probably with Jusepe de Ribera and Aniello Falcone, before making two trips to Rome in the second half of the 1630s. The following decade found him working in Florence, where among his patrons was Giovanni Carlo de’ Medici. It was in Florence that Rosa developed an interest in historical and mythological subjects, as well as in themes of witchcraft and the occult. An eccentric personality, he moved in literary and intellectual circles, which in turn inspired his idiosyncratic artistic vision. Returning to Rome in 1649, Rosa continued to paint unusual, often fantastical or macabre subjects alongside the paintings of battle scenes and wild landscapes with which he had first made a name for himself. In the late 1660s his compositions became darker and more oppressive. A gifted and prolific printmaker, Rosa produced over one hundred etchings, almost all of which were published and widely distributed in his lifetime.

Rosa was a remarkable draughtsman, and his spirited, exuberant drawings were highly praised by connoisseurs even in his own day. The bulk of the nine hundred or so surviving drawings by the artist are figure studies, usually in his preferred medium of pen and ink, and often enlivened with touches of wash. Many of the drawings from the early part of his career are signed, and these may have been sold to collectors or presented as gifts to friends or patrons. However, almost no signed drawings dating from after 1649 exist, and it has been suggested that, after his return to Rome, Rosa chose to keep most of his drawings for himself, and not part with them.

Rosa was a remarkable draughtsman, and his spirited, exuberant drawings were highly praised by connoisseurs even in his own day. The bulk of the nine hundred or so surviving drawings by the artist are figure studies, usually in his preferred medium of pen and ink, and often enlivened with touches of wash. Many of the drawings from the early part of his career are signed, and these may have been sold to collectors or presented as gifts to friends or patrons. However, almost no signed drawings dating from after 1649 exist, and it has been suggested that, after his return to Rome, Rosa chose to keep most of his drawings for himself, and not part with them.

Provenance

Jonathan Richardson, Senior, London (Lugt 2184), with his shelfmark (cf. Lugt 2983 and 2984) and on his mount

Probably his sale, London, Christopher Cock, 22 January to 8 February 1747

Alexander Scott Carter, Toronto (according to a note on the backing sheet)

Anonymous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 26 November 1970, lot 42

John Appleby, Jersey

Thence by descent until 2010.

Probably his sale, London, Christopher Cock, 22 January to 8 February 1747

Alexander Scott Carter, Toronto (according to a note on the backing sheet)

Anonymous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 26 November 1970, lot 42

John Appleby, Jersey

Thence by descent until 2010.

Literature

Michael Mahoney, The Drawings of Salvator Rosa, New York and London, 1977, Vol.I, p.440, no.45.8; Vol.II, fig.45.8 (as whereabouts unknown); Richard W. Wallace, The Etchings of Salvator Rosa, Princeton, 1979, p.168, no.37a (not illustrated); Paolo Bellini and Richard W. Wallace, ed., The Illustrated Bartsch. Vol.45 – Commentary: Italian Masters of the Seventeenth Century, 1990, p.393 under no. .057 (Bartsch 44).